Go West Young Woman, Go West!

I had been attending business college for six weeks when Mrs. Milbrandt decided to join her husband on the West Coast. Her widower brother was seeking defense work and planned to drive his 1938 Chevrolet sedan to the coast, taking along his five year old daughter, our landlady and her teenage son, Donald. I was invited to ride along with them for $15.00. It was October,1943, and that was a good price.

I looked forward to new experiences in a different state and packed my belongings into the striped, brown, fabric- covered, suitcase that had been a graduation present from my folks. Ma must have known I would be going somewhere for she had my initials BJM imprinted in gold near the handle.

The morning we were packed and ready to leave, my sister Dorothy and her husband Rudy brought Ma down to Aberdeen to bid us farewell. Rudy commented, “You’ll probably be back in six weeks.” I did not reply to his implied challenge, but I knew instantly that I would stay at least seven weeks, just to prove him wrong. The worldly possessions of all passengers were stuffed in the trunk or lumped and tied to the bumper and the top of the car. We rode with additional items wedged around our bodies and feet. The loaded sedan resembled the depression era pictures of Okies fleeing the dust bowl. It may have been crowded with four adults and one child riding in that sedan, but we were congenial. I do not recall a single unpleasant incident during the trip, with the exception of the little girl occasionally wetting her pants.

Each days drive ended in an auto court or an old hotel in one of the little towns sparsely spaced along the lonesome roads of Montana and Washington. Donald and I would sometimes take an evening walk, usually covering a small town in a half-hour.

We arrived in Seattle after several days of cross-country driving. Frank drove the car aboard the Seattle ferry for the one-hour ride to Bremerton. Disembarking, we found a small auto court high on a hill along the highway. This sparse cottage was our home for several days as we planned our next move. Donald and I slept on the floor. We were but five miles from Port Orchard, so close to our destination we could almost touch it.

It was October, 1943. The war was raging in Europe and in the Pacific. Battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, and destroyer escorts returned from the war zones to have damage repaired in the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton. The battleship, USS West Virginia, damaged in the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941, was still at the Yard undergoing repair for that damage. The Navy Yard trained new worker and there were jobs available for men and women in every trade category.

The population of Bremerton and the surrounding areas had swollen with people who had come from the depressed Middle-west to claim coveted Shipyard jobs. Housing for this population boom was a serious matter. Government housing developments spread to West Bremerton, across the Manette bridge to East Bremerton and finally across the bay into the hills behind Port Orchard, a little town of about a thousand people. Its downtown district was a row of small stores on the waterfront near the ferry dock.

Mr. Milbrandt didn’t qualify to rent one of the housing units that he had help to build. They were available only to families who had one member working in the Shipyard. This problem was quickly solved when I got a clerk-typist job in the Shipyard paying $1440 per year. This entitled me and my ‘family’ to project housing. We moved into a new three bedroom, one bath duplex located in the Port Orchard project. It was furnished with the basics: two new twin beds and a bureau in each of the three bedrooms, and an extra twin bed in the open living-dining-kitchen space. A low, wood-burning cook stove was the sole heat source. Free firewood was stored in a utility shed outside near the garbage can. A small ice box, table and six chairs completed the furnishings. Pull-down cambric shades covered all windows. Hardly a candidate for a House Beautiful feature story, but adequate.

The assignment of the three bedrooms was logical considering the variety of people in our group. Mr. and Mrs. Milbrandt shared one room. Another went to Frank and his little daughter. The Milbrandt’s 25 year old son came west and shared the third bedroom with Donald, his younger brother. I slept on the couch in the living-eating area and dressed and stored my possessions in the corner closet. After seven months, Frank and his daughter left and I used their vacated room.

The four men played cards and listened to the radio on the many rainy evenings. Winter had come and I would not be enduring the bitter South Dakota cold or snow. Just rain. This alone made the Puget Sound area seem like pure heaven. Since I had to catch an early morning bus going to the Port Orchard Ferry Dock, I retired many nights while they were still playing cards and smoking within 4 feet of my bed. It was noisy but it didn’t keep me awake.

Many Shipyard workers, who had been unemployed in their home states, now had their first jobs since the depression. Some drove 1930’s and early 1940’s automobiles. Automakers were now building war machines, not cars. Gasoline was rationed. Public bus and ferry transportation was continually expanded to accommodate the growing population. At one time the shipyard had over 30,000 employees working in round-the- clock shifts.

Not since the first settling of the Western part of our nation had so many people from many cultures and geographical areas been uprooted and thrown together to accomplish a common goal. It was a remarkable experience. Everyone in the project was a newcomer to the state. Regional accents and colloquialisms abounded and the usual conversation opener was “Where ya from?” We were dropped into this housing project melting pot eager to meet our neighbors who generously shared some basic information needed to get along. They guided me through my very first experience of catching buses and ferries. It didn’t take long to learn that anyone who stepped out of their door early in the morning wearing a shipyard badge was about to catch the bus going to the Port Orchard Ferry. I just followed them. Everybody worked in the Shipyard. If the first little ferry was crammed full, one waited at the head of the line and boarded the next boat that tied up at the dock.

There were many ferries transporting workers across the bay to the Shipyard. The vessels hurried into service during this time were a motley collection of maritime wonders, retrofitted and put back to work. The smallest of the Port Orchard-Bremerton ferries appeared to be nothing more than the hollowed-out, twenty-five foot hull of a noisy, noxious, snorting boat that could transport about thirty people. A roof protected passengers from rain during the roaring fifteen minute ride across the water to Bremerton. Bench seats, with life preservers stored below, were built along each bulkhead. Some passengers sat on the vibrating engine enclosure in the center area. The warmly dressed Captain hunched over the wheel in the cabin, leaving his post only to assist his agile, young deckhand in tying this throbbing vessel to the boarding ramp. The youth, dressed in a slicker raincoat and wool stocking cap, made extraordinary leaps from the bouncing boat to the pier in order to secure the lines. His was more than a job, it was a performance. The passengers were the spectators. He gave every impression of enjoying the role.

The mornings were damp. We walked in an orderly line down the wavering wooden ramp and stepped over the !2 inch sill into the small ferry boat, always wary of a sudden wave that might lurch the boat away from the dock. There was little talking during the journey as every word had to be shouted over the engine noise. Some of the larger ferries sailing this route had upper decks where passengers gathered at the rail to watch the belching smoke and the hypnotic wake of the ferry trailing the course toward Bremerton.

What a wide variety of passengers we were! There were tradesmen such as pipe fitters, ship-fitters and coppersmiths. They wore overalls covered by bulky jackets and carried black metal, dome-top lunch pails. Women had never before worked in such great numbers. There were tradeswomen who worked alongside the men on the ships and in the machine shops. They wore denim coveralls and a specially designed, snooded denim cap. Some shop women wrapped their heads with white cotton dishtowels, turban-style.

Also boarding the ferry were secretaries and clerks, like myself, all eager to look our very best at what were probably our first jobs. We wore high heels, skirts and raincoats. Decorative bandannas covered hairpins and curlers during the ferry ride. We took no chance of the damp morning air ruining our hairdos before we reached our office building. The mirrors in the womens restrooms were crowded as we removed the curlers, combed out the pinned curls, styled our hair and exchanged makeup tips during the half-hour before work began. When we punched the circular time clock, after all that effort, we must have been a stunning looking bunch.

Office workers wore skirts and dresses to work. We acquired nicer clothing using the layaway plan at Bremer’s Department Store. Our rayon or nylon stockings had seams up the back of the leg. “Are my seams straight?” was a common question the young women asked each other. One quickly learned that hosiery manufactures didn’t know about quality control. A pair of hosiery was comprised of two separate stockings, there were no pantyhose. When purchasing hosiery, the customer specified the stocking length desired and the clerk frequently searched in two or three boxes before she found the requested length. She measured every pair, finding different lengths in the same box. Nylon stockings were scarce and many women wore leg makeup instead of hosiery. This dark tan liquid was slathered on our legs and an imitation seam was drawn up the back of the calf using an eyebrow pencil. The line began at the heel and disappeared under the skirt hem. Without a seam, even an artificial one, people might think you were bare-legged. Heaven forbid! When Bremer’s Department Store received one of those rare shipments of nylon hosiery, a 50 foot long queue gathered quickly, spilling out the doorways and down the sidewalk. It was wise to take a place in these lines and then inquire of the others what they were waiting for. Hopefully it was nylon hosiery. Sales were always limited to one or two pair per person, depending on the supply. Most women wore an elastic girdle to keep their stockings in place. My weight at that time barely exceeded a 110 pounds, but I still wore a girdle. At that time nice girls did not walk around with two bumps showing on their rear end. We even wore girdles when we wore slacks. No bumps, just flat as a board. Ah yes, we were certainly nice, no one would confuse us with some of those loose girls out on Pacific Avenue.

When the ferry docked in Bremerton we filed down the undulating ramp and walked the short block to the entrance gate of Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. The turnstile gates were policed by Marines who verified our metal identification badges as we entered. The badges, the size of a silver dollar, featured our photograph and identification number. Forgetting to wear it meant a delay in getting to your job. You would be sent into the adjoining Labor Board Building and put through a lengthy identification procedure requiring completion of many documents. The long waiting bench was always full of forgetful people with doleful expressions and no badges, anxious to get to their jobs and earn some money. Once their employment was verified, a temporary pass was issued for that day. It was an irritating delay one did not care to repeat. Some workers never removed the badges from their coats so they were never delayed at the gate. They could be seen at stores or movies during evenings and weekends, their badges displayed on their jackets.

We office girls hid the unattractive badges by pinning them to the underside of our coat lapels. We turned the lapel and revealed the badge to the Marine guard as we passed through the gate. One morning, I was directly behind a girl entering the turnstile. She neglected to flip her lapel and show the hidden badge. The Marine guard brusquely told her to put the badge where he could see it. Her reply was brash for a woman in 1944. She remarked “Where do you want me to put it? On my ass? That is the only place you Marines look anyway!”

All new Shipyard employees were required to attend a short indoctrination which included experience in a tear gas chamber. About a dozen people at a time, donned gas masks and entered an airtight room. After listening to a short talk we were told to remove our masks and hand them to the person at the door as we exited. In those three steps to the door we found we were in a room of tear gas and the tears cascaded down our cheeks. We now knew how to use the gas masks that were in all of our office desks.

I worked in the Shipyard Production Department along with a dozen progressmen and twenty clerks. The desks of young Naval officers were across the aisle. Our cluster of clerk- typists were well monitored by our supervisor, Mr. Curtis Workell. The days must have been boring for him. He sat at his bare-topped oak desk facing us from the far wall. There was no ‘In’ or ‘Out’ basket cluttering his highly polished desk. His whole days work seemed to be contained in a dozen 3” x 5” cards neatly piled under the palm of his hand. He sometimes layered them in short solitaire-like columns or in carefully sorted little stacks. Other than the time spent sorting his cards, and an occasional twenty-foot stroll over to see the head progressman, Mr. Workell’s day was spent with his hands folded over the mysterious cards and peering at us through thick glasses that diminished his eyes to brown pinpoints. His secretary was required to time us when we went to the rest room.

Many of us were recent high school graduates and anxious to learn. Lucy Jones, an outspoken grandmotherly woman in our office, had many years experience in the Shipyard and she was wise to the ways of government civil service. She guided and chided us onto the correct track as we wandered the bureaucratic maze. There was high rate of employee turnover. Young women, who were married to servicemen, would resign their jobs to follow their husbands to his new base assignment. When their spouses’ ships sailed for the Pacific war theater, the wives quit their jobs and went home to their families.

Our desks were pushed together so the typists faced each other. This meant one girl had her back to Mr. Workman. Friendly talking was forbidden, even if we had nothing to do. A few softly whispered comments among two desk partners would cause Mr. Workman to focus those fiercely penetrating brown eyes on you. One might say he was skilled at the art of non-verbal communication. He knew that on some days we were unoccupied while waiting for certain job papers to arrive; but for him it was imperative that we LOOK busy. After all, other Civil Service office managers and Captain Nibecker over in that glass- enclosed corner office might spot the fact that Mr. Workman had built a small secretarial empire who were not always busy. A large staff enhanced Mr. Workman’s job description and could help him achieve a salary boost to the next pay grade. We became skilled at looking busy when we were not. Some would type personal letters during these quiet periods and I took the time to sketch and draw. Never before had such a wonderful array of drawing paper, India ink and speed ball pen points been so readily available to me.

The clerk-typists who smoked would light up cigarettes, place their elbows on the desk, and hold the cigarette aloft. It was usually stained with the trendy Black Cherry colored lipstick. They narrowed their eyes as they watched the exhaled smoke curl around their fluorescent desk lamp. Gazing through their smoke screen they would idly check out which of the young Ensigns and Lieutenants were at their desks across the aisle. Although we dated the young officers, we were careful not to talk to them at their desks, nor did they come to ours.

We wore skirts topped with blouses or boxy crew-necked ‘Sloppy Joe’ sweaters. We bought business suits as we earned more money. Leather shoes were rationed during the war, but we soon learned that straw wedgie shoes and huaraches from Mexico required no ration stamps. One girl in our office discovered that wooden clog shoes could also be purchased without ration stamps. The clip-clop of her wooden soles combined with the scrunching squeak of woven huaraches sounded like a herd of appaloosas bounding down the red battleship linoleum corridors of the Administration Building.

We ate lunch in the office cafeteria. It was there I first tasted asparagus, ripe olives and Boston Cream Pie. I had never seen ripe olives and wondered what to do with those little black balls rolling around on the salad plate. I noted one woman ate them so I did the same. I felt she must have made a mistake as those little black things seemed pretty awful.

One of the office girls invited me to spend the weekend at her parent’s home in Shelton. I was pleased to be invited, even though I didn’t know her very well. After work on Friday night, we hopped the bus for the half-hour ride to Shelton.

I learned that I was the guest in a household that was extremely involved in their church. Immediately after dinner she and I went to church for the Friday night youth meeting. Saturday morning we went back to church to prepare for something else. Saturday evening we went back to church to practice whatever song was going to be sung in church the next day. The young people mingled briefly after practice. Sunday morning we got up and, guess what, we went to church for a ‘before church’ session. Before the regular church service, I found myself acutely uncomfortable sitting in some little room in a ‘prayer circle’ meeting. Everyone sat in a circle and each, in turn, said a sentence prayer. I had not expected to be put in a position like this. One by one the short murmured prayers clicked off. Chair by chair it was getting closer to my turn. I was petrified. There was a painfully long and terribly awkward silence between the prayer of the person on my right and that of the person on my left who finally realized I was not participating.

A few minutes later we went into the church service. There was a special time reserved for those who wanted to be ‘saved’ and the Minister pleaded for those persons to come forward to the front of the church --in fact, he gave those sinners several opportunities during repeated appeals. I sensed several meaningful glances in my direction at this time and finally realized I had been brought and guided there to participate in that specific event. I was sorry to disappoint my friend, and resented the trap that had been so carefully set. I did not want to be where I was. If the girl had told me how active she was in her church and the plans she had for me I would never had gone. Oh yes, there was also a Sunday afternoon church activity before we boarded the bus back to Bremerton. I was glad to get home!

We typed documents with five or six carbon copies and became skilled at making erasures, rubbing out the mistake on each separate copy before proceeding. The manual Underwood typewriters had to be heavily stroked to make the printing show through all carbons and the last tissue was barely legible. One learned to become a skillful and accurate typist.

Each progressman represented a different trade. Daily, they covered their suits with raincoats, donned personalized hard hats and boarded the ships to verify the progress of various jobs.

It did not take long to let my supervisors know that I was just no ordinary little clerk, no sir, I could draw the nice box lettering needed for the big 30” x 40” line graphs made for every ship undergoing work in the yard. They assigned the job to me. This was more interesting than routine clerical work and I updated them daily by transferring expended work hours for each trade to each graph. It was nice to see Captain Nibecker and the head progressmen slide out the big wooden boards from the big cabinet and study the charts. Soon there were opportunities to design Golf and Country Club invitations for one of the men in the office as well as light- hearted cartoon-type cards and posters for departures and promotions of fellow employees and supervisors. These little art jobs, not on my Civil Service Job Description, provided an escape from some very routine work. I had barely learned to use the comptometer myself, when I began teaching it to new girls.

It was a moving sight to see these huge warships first enter the Puget Sound after spending a period of time in the Pacific battles. They sailed past Bainbridge Island and the net-tending vessels, on toward Bremerton, announcing their return with music. The ship’s band sat in the bow of the ship or on the top deck of the aircraft carriers. The popular songs and spirited music echoed among the shoreline hills as they passed through the inlet. The perimeters of the decks were lined with the sailors standing at attention wearing dress uniforms, blue in the winter, white in the summer. It was a thoughtful custom and an impressive show. Those sailors, who were scheduled for liberty or leave, had their sea bags packed and ready to depart as soon as the ship tied up.

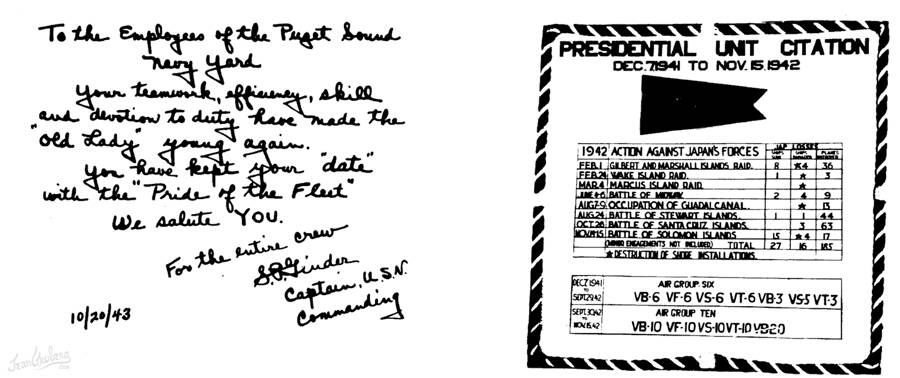

The repaired ships received a finishing coat of gray-toned, geometric zig-zag camouflage and were taken on shake-down cruises before going back into service. Their Commanders sent cards to the Shipyard workers thanking them for their efforts. These cards usually featured a picture of the vessel on the front and a small note of appreciation written inside along with charts showing the ship’s battle achievements. Symbols for each enemy submarine, airplane and ship sunk formed little lines across the chart. The appreciation cards, as well as the workers’ visits aboard the war-damaged USS Bunker Hill were probably designed as morale boosters to motivate shipyard workers and make them aware of the importance of quickly getting these ships back in service.

Our office received a classified listing of names and categories of ships that were sunk in battle. It was my somber job to go to the locked file of the head progressman, remove the thick register of all the ships in the Navy and draw a line through the names of the sunken ships, listing the date they were sunk. I felt like the grim reaper. There were probably similar logs being maintained in other departments.

I walked past three dry docks on my way to the office each morning. These huge cement holes were dug below sea level and projected into the shipyard from the bay. A gate-like caisson kept bay water from flowing into the dock. The vertical walls were lined with cement terraces and a row of immense wooden blocks were anchored down the center of its floor. To bring a ship into the dry dock, the caisson was swung open so the bay water flowed in and filled the dock. The ship was guided into the filled dry dock and the caisson closed. As the water was pumped from the dock, the ship gently lowered and was carefully guided to rest on the blocks.

Sometimes a school of herring swam into the dry dock along with the ship and became trapped when the water was drained. The fluttering, flopping fish would be a foot deep on the dock floor. Workers scooped buckets of herring to take home for pickling. The buckets of fish were carried past the Marine guards at the Shipyard gates on those nights without the need of a special property pass.

The battleship USS West Virginia was in dry dock undergoing repair for damage caused during the Pearl Harbor attack. One of the progressmen, took me aboard on one of his daily rounds. It was impressive.

Some dry docks near our office building were very large and accommodated full- sized aircraft carriers. A secretary in our office was dating an officer on the carrier USS Saratoga. He took a few clerks aboard for lunch in the Officers’ Wardroom and gave us a tour of the flight and hangar decks. We liked that.

Several months later the aircraft carrier USS Bunker Hill came into port. It was put in dry dock for repair of severe fire damage caused by a Kamikaze plane. Japanese pilots sacrificed their lives in terrible assignments requiring them to crash their heavily-armed planes into our ships at sea. All Shipyard Workers were given time off to go aboard and walk through the flight and hangar decks to witness the severity of the damage. They shuffled aboard in a silent, slow moving line. The damage was awesome and frightening to contemplate. Our office staff went aboard together.

One would sometimes hear a tremendous boom when they tested the catapult that launched the planes on the deck of aircraft carriers that were undergoing repair. A progressman said that a log was substituted for an airplane for this test. The log must have hurled like a missile from the ship’s deck and landed somewhere out in Puget Sound.

In 1945 Shipyard workers were again briefly excused from work. This time we gathered around the perimeter of the big dry dock next to our building. President Roosevelt spoke from the bow of a destroyer that was under repair in that dock. He was accompanied by Admiral Leahy, several military men on his staff, his physician, his dog ‘Fala’ and his daughter Anna. His talk was a morale booster. He told us of the good job the battleship USS Nevada had done in the bombardment of the Normandy coast after having been raised from the water at Pearl Harbor and repaired at our marvelous Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. The workers surrounding the dock cheered approvingly after his praise. The newspaper estimated there were 20,000 workers in attendance.

I only went to three USO sponsored dances,. We were told we must dance with anyone who asked us and after a few of those dances I decided I preferred having the right of refusal and did not return. Some ships held their own Ship Dances at a building just inside the Shipyard gates. The USO encouraged us to attend these dances. I went to one ship dance given by the battleship USS Washington; it was attended by both enlisted men and officers. There was a good orchestra and a large very well behaved crowd.

All of us, guys and girls alike, were probably between 18 and 23 years of age, uprooted from our families and familiar places. We were all looking for a friend in a strange environment. For the servicemen, it was an opportunity to visit with someone in a homelike environment instead of a steel ship and they behaved like gentlemen. The majority of young men I met were nice polite kids who missed being at home and wanted a friend for talking, walking, dancing and movies. They were pulled into a vicious war at an early age and seemed like high school friends. Our country was fortunate to have them.

Displacing the personnel on huge ships during overhauls that lasted several months presented housing and feeding problems which the Navy solved in various ways. In one instance they made use of the SS Yale, an old wooden cruise ship that had sailed from San Francisco to Los Angeles in its Jean Mertz Groberg 141 early days. It was painted a sad wartime gray/khaki color and was moored along one of the isolated piers. It became a floating sleeping dormitory for sailors displaced while their ships were undergoing repair. A galley to feed them was built alongside the Administration Building where I worked. A two foot space separated the two buildings. The windows of the galley and mess hall aligned with those of our office building in several locations. From our desks we could see the sailors standing in the mess line waiting to pick up their trays, and of course we were interested in looking. The sailor’s main entertainment while standing in the chow line was to get the attention of any girl in the office. They would dance, mug, whistle and point until one of their Chiefs or Officers told them to settle down. Mr. Workman had placed his desk squarely in front of the set of windows that lined up with the most direct view into the mess hall. To look toward those windows meant you had to look directly into the bottle-bottom glasses of Mr. Workman. Only the boldest of clerks cared to brave his cold, killing stare.

After several months, another person in our government housing got Shipyard employment. This freed me to move into studio apartment housing in Bremerton. The studio units, probably twenty to thirty in a cluster, were built by the government to house single female government, employees. I put my name on the waiting list and the housing office paired me up with a girl named Nora. The small studio room was furnished with two twin beds. There was a two burner portable hot plate on a short counter and a portable oven about a foot square that could be set over a burner for baking. It was fun living around so many young people for a change, but it was an eye-opening three or four months. I had never been around girls like many of them. Some were married to servicemen who were away at war, but they didn’t allow a little thing like that to restrict their social life.

A cute, petite young woman named Bea lived in a studio apartment a few units away from ours. She worked as a welder on ships in the Shipyard and always wore denim coveralls and a visored cap to work.

The layout of the apartments was similar to that of a motel and it was easy to notice the exceptional amount of nighttime activity coming and going to Bea’s small unit. I encountered her on a downtown street several years after the war ended. She told me she had bought the Dunhill Rooms, a flat of rooms over an appliance store in the downtown area. I congratulated her on her good fortune and wished her well as a manager of this small hotel. I later learned that the Dunhill Rooms was an active house of prostitution. Several of these types of upstairs establishments were located in the area for many years.

One night I double-dated with my studio- apartment room mate. We four were coming home from the movie in a taxicab at 10:30 p.m.. Nora’s boyfriend was a sailor off the battleship USS Washington. They were hell-bent on getting married before his ship sailed the following day. At 11 p.m. our taxi pulled up in front of the parsonage of the Swedish Lutheran Church. The cab driver waited as we walked up the sidewalk behind this romantic couple who were already on the porch and knocking on the darkened door. A gray-haired minister, tying his frumpy bathrobe closed, answered their urgent knock. He did not sympathize with their passionate appeal to please marry them, right NOW, and it was no surprise that he declined to perform a midnight wedding. Nora and Ralph had been so impulsive they didn’t have a marriage license. Advance planning was not their strong point. I heard that they did marry the next time the ship was in port. By that time I had moved. Being assigned room mates by a housing agency was not an ideal arrangement.

I was in the studio apartment housing but a few months and was anxious to find a different place to live. Everyone was looking for housing, not only Shipyard workers, but also wives of the Navy men whose ships were in port. Some of the servicemen and their families were housed in the Veterans Home on the hill overlooking the bay in the Port Orchard area. There was a definite housing shortage and many Bremerton residents converted their basements into rental units by covering the cement walls with knotty pine and installing a bathroom. None had a telephone, but most basement tenants were free to receive calls on the landlord’s upstairs phone.

I was happy when my friend Betty Hartwig and her room mate asked me to share a one-room basement apartment at the home of Betty’s Uncle. We shared the $40 monthly rent. The apartment was merely a single room with a double bed, fold-down davenport and a bathroom. Before long the Hartwigs asked us to make room for another niece, Ann, who was coming to the coast after graduating from high school in Kansas. We were crowded with four girls, two of them nieces of the landlord. We took turns sleeping on the davenport, cooked on a two burner hot plate, ate our evening meal together and shared the grocery bill,. The girls were all upbeat and got along very well in very tight surroundings.

The civilian attitude toward the servicemen during the war years was one of complete acceptance and generosity. The community couldn’t do enough for the them. In 1944 our landlords invited all four of us downstairs renters to come upstairs for Thanksgiving dinner. While the plates were being set on the table, Mrs. Hartwig asked her husband to drive the 3 miles to the downtown YMCA and see if there were any servicemen sitting in the lobby who might like to share the holiday meal. Now there was a lady who knew how to liven up a Thanksgiving dinner! Mr. Hartwig returned from the ‘Y’ with three sailors and we four renters from that downstairs apartment were mighty pleased at this pleasant turn of events. That made Thanksgiving a lot more fun.

Betty found that living with a cousin and having an Uncle upstairs was more family scrutiny than she wanted. A few months later she and Mary moved into another knotty-pine basement apartment three blocks away. It had a real stove, sloping skylight windows over the sink, a separate bedroom and a living room with a fold-down davenport also for $40 per month. I was left with Ann, the Kansas niece who had been foisted upon us by the upstairs landlords. She was younger, sweet, cute, immature and not terribly smart. She worked at a different location, had different friends and frequently went to Seattle on dates. When going there on a date, one had to be very aware of the ferry schedule. The last ferry to Bremerton left somewhere around midnight or 1 a.m., and there was no ferry again until around 5.a.m.. Mary seemed to be a slow learner, far too often she would not get home until morning saying they had missed the last ferry. I have no idea where she spent the night . She didn’t say and I didn’t want to know, I wasn’t her Mother. I do know that after a few months she hurried home to Kansas. The Hartwigs divulged that she gave birth to a baby a few months after her return to Kansas. Probably her parents had hoped she would discontinue her promiscuous behavior if she went to the coast after graduation. It didn’t work..

I asked Marge, a girl from the Black Hills area of South Dakota to share the apartment with me. It was nice to find an easy-going, intelligent, reliable roommate with a similar background and values. There were no surprises when living with Marge, other than the time she decided to make a pie from a can of plums. She dumped l cup of sugar on an unbaked crust, poured the plums on top of the sugar and applied the top crust. The sugar formed a crystalline brittle crust on the bottom of the baked pie and the plums had big pits. One time Marge’s mother came from South Dakota for a visit. She mistook the squat white jar of ‘Ever Dry’ Deodorant in the bathroom for Cold Cream and applied it to her face. Before long she came out asking what was wrong with the Cold Cream. I imagine that really tightened up the wrinkles.

Marge and I enjoyed walking the hilly streets near our apartment. It was such a lovely view of Puget Sound. We could see the ferries and other shipping moving through the inlets and channels to Seattle, Port Orchard and Bainbridge Island. One Sunday afternoon we rode a city bus to the last stop on the edge of town and began walking the shoreline road. After walking a quarter mile we noticed a small Naval craft out in the channel with five sailors aboard. They waved at us in a friendly manner from their boat a hundred yards off shore. We were safe on land and felt very secure returning a friendly wave as we walked along. We weren’t aware that their boat was a landing craft. As soon as we responded to their wave the boat made a sharp right-angle turn and headed straight for the beach in our direction. Marge and I didn’t feel quite so friendly any more. We reversed direction and broke into a run to get back to that bus stop on the edge of town. The landing craft went on its way. The fun was over.

We danced almost every weekend. The Sheridan Park Recreation Center and the Del Marco Ballroom ended their first dance sessions at 12:30 a.m. sending everyone outdoors only to reopen and sell tickets for Swing Shift dances a half- hour later at 1:00 a.m.. The Swing Shift session lasted until 4:00 a.m. and gave swing workers an after-work social activity at an unconventional time. I only attended two of these, finding that it was just too late to stay up. Occasionally we took the Seattle Ferry to go to a dance across the bay.

In West Bremerton the Perl Maurer dance hall held dances on both weekend nights Modern dance was featured on Friday night. Saturday was reserved for old time dances and drew a mixed crowd of young and old alike. If you didn’t know how to dance the old time steps, your partner would teach you. We learned to do the polka, schottische, Swedish Waltz, Varsouvienne, Spanish Waltz and square dance.

Lyle and I got involved in a square dance one Saturday night. The older people who had been attending these dances for years guided us through the steps and shoved us in the proper direction so the whole routine wasn’t ruined for all. During this sequence, a guy and a gal came from opposite sides of the circle, met in the middle, hooked elbows and twirled a time or two. When it was Lyle’s turn, he met one hefty old lady in the center of the circle and she swung him by his elbow with such vigor that he landed on his behind on the floor. When the dance closed at 12:30 a.m. there was always a bus waiting in front of the dance hall to take the dancing sailors and civilians the three miles back into Bremerton.

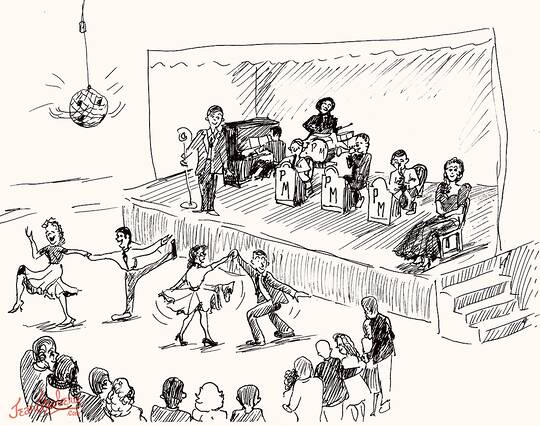

These six to eight piece dance bands that did their very best to play the popular songs like the famous big bands. There was always a vocalist. A male vocalist and the band members wore similar suits or blazers. The female vocalist always wore a long formal, a determined smile and sometimes elbow-length gloves and a corsage. Every hair was in place and her makeup perfect. Between performances she sat facing the audience on a chair at the corner of the stage. Hers was a glamorous job, like a small-time movie star.

If we didn’t have dates, Marge and I went to the dances together, and always come home together. That was our agreement, neither was left stranded. Girls who came as singles always congregated in one area between dance sets and the single guys knew where to find them.

If the band made a quick switch from a slow to a fast song in the middle of a set, the experienced jitterbug couples claimed a floor area in front of the stage while the other dancers who were marooned on the dance floor gathered around to watch these extroverts show their stuff. The full skirts would swirl and flare wildly during some of the jitterbug spins and many of the girls would modestly drop one hand to restrain the lift of the skirt. This reduced the chance of a radical revelation during a radical revolution. Girls never wore slacks to dances or on dates.