Farm Life

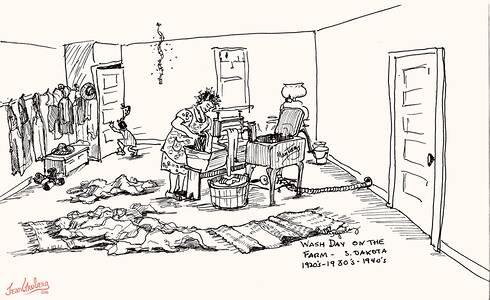

The sharp, firecracker pop of Ma’s gas washing machine early in the morning signaled wash day. It was always a noisy awakening for we three youngest kids sharing the second bed in Ma and Pa’s bedroom. We would first hear the older girls pulling the sheets off of Ma and Pa’s tilting, nodding iron bed. Too many kids jumping on their innerspring mattress had weakened the bed frame causing the foot and head ends to bow toward each other.

It would not be long before a quick yank of the sheet beneath us would send us spinning onto the striped ticking of the stained feather bed. As the older girls left home to work elsewhere for money, we gradually took their place doing this work. There were no little kids left for us to roll out of bed and not so many clothes to wash.

Once awakened, we stepped around the sorted piles of soiled clothing on the kitchen and dining room floors. Wash day was in full swing. It was an all-day affair, every room was in shambles except the living room. Since we had no extra bed linens, the sheets were pulled from all beds, washed, hung out to dry and were back on the beds by late afternoon.

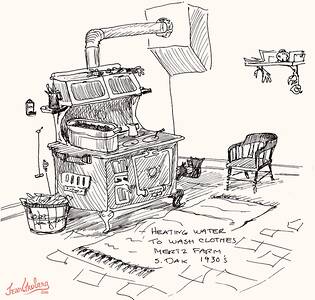

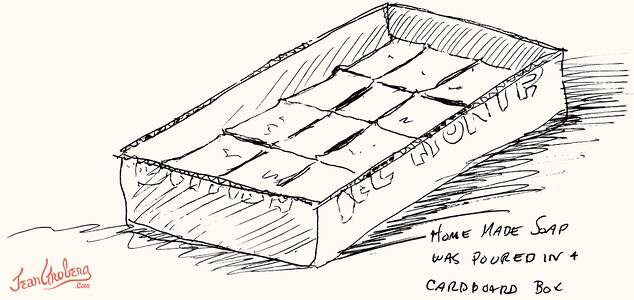

The wash water was heated in a 20-gallon oval, copper boiler on the kitchen range which was wolfing corncobs by the basket full. Homemade soap shavings floated and bubbled on top of the steaming water and Ma prodded and poked simmering dishtowels with her broom handle ‘wash stick’. This simple tool, bleached to a silvery gray from hot water and lye soap, was handy for lifting hot wet clothes from the boiler into buckets and then into the washing machine, and once more from the washer up to the wringer.

The gas motor of the square Maytag washing machine pounded away like a rapidly firing gun. A flexible metal exhaust hose poked through a hole in the wall belching blue smoke into the outdoors with each firing. The noise assaulted the house and echoed about farm buildings. The men could hear it out in the fields. Our world turned upside down on wash day.

One of the older girls was usually washing the cream separator discs in a dishpan at the end of the kitchen table so we poured a bowl of corn flakes and ate at the other end. We made no attempt to converse over the noise of the firing washing machine.

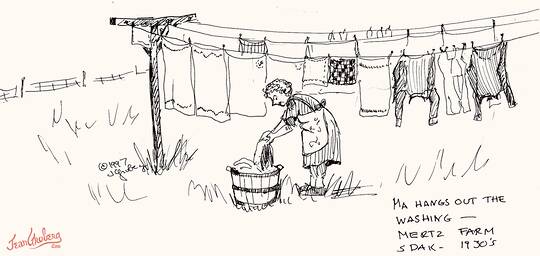

After breakfast there was a full apple basket of wet clothes needing hanging on the wire clotheslines that were strung between two yard posts. Two of us would grasp a handle and carry the wet clothes to the clothesline. Bruce and Joyce would take another basket to the hog yard to pick up more corncobs for the fire to keep the boiler of water hot. There was something for everyone to do. You couldn’t escape the labors of wash day, nor its noise.

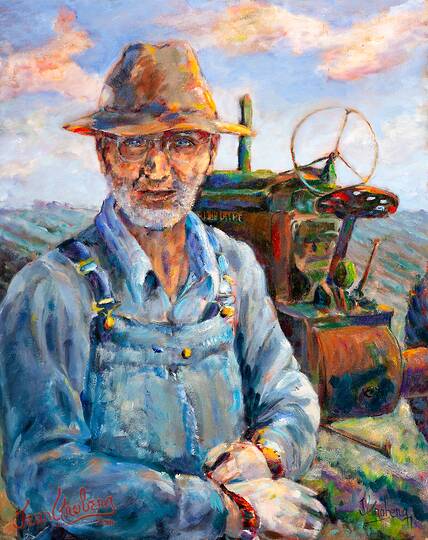

The piles of clothes on the floor slowly disappeared into the washing machine, the lighter colors first, then the worn towels, men’s work shirts and overalls. At mid-morning, we would start cooking meat and peeling potatoes for the noon dinner. Sometimes we snapped the tips and stems from string beans or podded peas that we picked from the garden. Other times we picked ears of field corn for dinner, being careful to avoid ears afflicted with a revolting smut fungus.

All washing activities halted while dinner was served in the dining room.

After dinner, the men went back to the field, Helen, a barely over 12, was out there working right with them. We washed the dinner dishes while Ma and the older girls restarted the machine and finished the last few loads of overalls and rag rugs. The copper boiler on the kitchen stove was now empty, the floors cleared of dirty clothes and the clotheslines were full. The gray water in the machine told the tale of many loads of heavily-soiled clothes. The final rug usually jammed its way through the wringer and when it dropped into the basket, Ma turned off the motor.

How beautiful the silence, the Maytag motor monster had been killed and stilled. It would have been extremely difficult to keep the clothing of a large family clean without a washing machine, even a loud one. How happy the women must have been when they could afford to buy one of these popping machines.

But wash day was not yet over. The galvanized tubs of rinse water were carried outside and dumped on the ground by a couple of the bigger kids. The warm, soapy water remaining in the boiler and the machine was poured into a bucket and used for scrubbing the kitchen linoleum. The floor was mopped with a clip mop, outfitted with cotton-knit winter underwear scraps and immediately smothered with several layers of the Aberdeen American Newspaper that remained in place for several days. Each day the uppermost newspaper would be carefully folded to capture any sand, and then removed. When the last newspaper was lifted, the clean, protected floor was revealed. In a few more days the exposed floor would be dirty and it would again be wash day.

The wooden hallway floor in the wash room was also mopped and traffic areas were also covered with more newspapers. The washing machine was shoved into the corner under the long line of hanging mens work jackets, overalls, sheepskin coats and assorted hats. The galvanized tubs and the swaying wash bench that held them were returned to the back porch. The messy, noisy part of wash day was over.

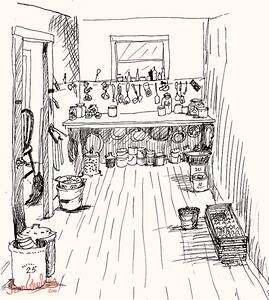

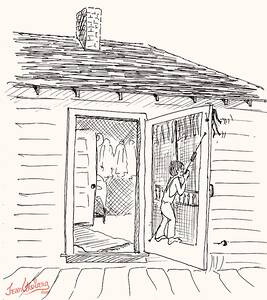

One Monday morning in the early 1930’s, we were making lunch sandwiches and getting ready for school. Ma was in the pantry and she was mad. It was just one of those mornings. She didn’t raise her voice often, but there was something about that cluttered pantry on Monday mornings that set her off. She pried a cookie sheet from the tangled array of pots and The Pantrypans, flipped it toward the pantry doorway where it landed on the aluminum kettle with the scorched wooden handle. I hated these Monday mornings.

I knew why the pantry was messy on that particular morning. The night before had been one of those balmy September evenings when we played outside after supper time. We were sorting discarded shotgun shells dropped by hunters along the road to the country school. It was dark when we finally went indoors to wash the dishes, The warmed dishpan of water was waiting on the kitchen range and the gas lamp had already been taken to the living room where Ma and Pa had settled for the evening. He was probably playing a game of solitaire using a wooden chair seat for a table and she usually read a magazine.

The kerosene lamp we used in the kitchen gave a dim light. No problem. We four sisters were more intent on enjoying ourselves than doing dishes. We moved the dishwater pan from the range to the kitchen table and sang while we worked. There was something about sloshing that bar of homemade soap in the dishpan that brought out considerable musical genius. We sang cowboy songs in fractured harmony or the latest popular songs as heard on the Saturday night ‘Hit Parade’ radio show. It’s too bad that Lawrence Welk was busy up across the North Dakota border getting his band started. He might have gone farther much faster had he heard about the Mertz Sisters Kitchen Singers down in South Dakota.

But back to the dish washing --I was the delegated ‘dish wiper’ on the previous night and stored the dried pots and pans in the dark pantry. The ceiling- high shelves were burdened with more stuff than they could ever hold. There was never an open space or an open nail for clean pots and pans. If a pan balked at being wedged in some crevice in the dark pantry, I just piled it on top of something already on the floor. That’s what we all did. If the washed pans weren’t spotless, we didn’t complain. Such talent of ours was wasted on humble pursuits such as dish washing.

Ah, how we sang and how we danced on Sunday night. But in the cold, harsh light of Monday morning, things were not so much fun. Ma was still worked up in the pantry. I quietly spooned the homemade sandwich spread onto slices of her white bread, and secretly wished she would stop the ranting and raving. I hated that noise. I dropped the unwrapped sandwiches into the syrup pails., And busied myself looking for a lid to fit my lunch pail. I had nothing to say

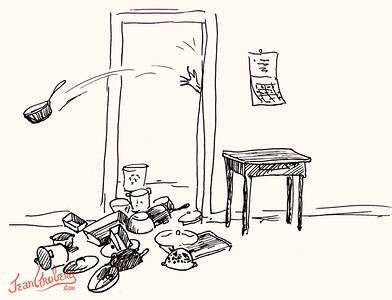

The pans kept flying out of the pantry as Ma chattered her frustration, “And this doesn’t go here,” and “Who put that in there?” or, “This didn’t even get washed!” Ma had really worked up a steam. We couldn’t hear everything she said because of the clattering of the falling kettles. I didn’t mind missing any of that torrent of words, not one bit. By now she was digging into a lower layer of pots and pans hurriedly dropped by some other offender on a previous night. Now THOSE were not MY responsibility. There was a little comfort in knowing that.

I found a lid, pressed it firmly onto my lunch pail and quietly slipped out the screen door with Verna, Joyce and Bruce and headed down the road toward school. Ma’s angry voice and the sounds of banging metal pots faded as we put some distance between us.

I was glad to go to school and the walk gave me time to put the messy pantry completely out of my mind. Ma would have seven hours to cool off before we got home and it would never be mentioned again. Until next time. There was always a next time.

I was about eight or nine years old that late spring day when I stood on the back porch and watched a whirlwind begin a spiral dance by the machine shed. It picked up momentum as it spun across the yard in my direction. Tumbleweeds, feathers and sand whirred in the vortex of the upward spiral. I squeezed my eyes tightly shut and felt the grit pepper my bare legs and face as the wind spun by. Then it suddenly dissipated. Tumbleweeds and feathers fell to the ground.

I was pulled away from this windy, gritty scene when Ma sent me to the cellar to get a chunk of salt pork for supper. She was probably going to simmer it with beans.

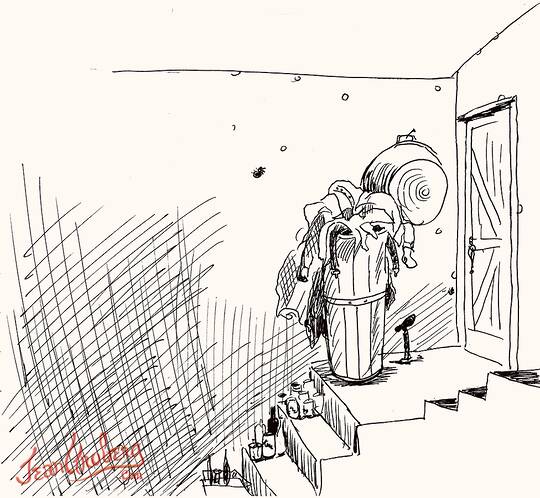

I grabbed a handful of wooden matches from the metal matchbox hanging behind the stove and opened the cellar door. On the top landing the tall, round banana basket that served as a laundry basket was teetering with an unbalanced load of dirty clothes. One more carelessly thrown towel or shirt and it would again topple down the cellar steps. The ends of the steps were cluttered with empty canning jars destined The Cellar Landing for eventual cellar storage. Dome-shaped, fuzzy nests of large, beige, harmless spiders clung to the cement walls. At the bottom step, I pushed open the cellar door and scratched another match on the cement wall. The aroma of the potato bin seemed stronger than usual. The flame fluttered as I moved along the darkened corridor and located the twenty- gallon crocks where big chunks of pork had cured in brine since the last butchering. I slid back the round wooden lid. Most of the meat was gone and the brine level was low. I leaned over and lower a freshly lighted match into the deep crock. Five pieces of meat, about 4 pounds each, floated in the bottom of the crock. In addition, there was an unexpected piece of meat in the process of being pickled. A dead mouse floated on the surface.

Someone on a previous visit, in their haste to leave the spooky cellar, had not properly replaced the lid and the unfortunate mouse had fallen in. How long ago? Should I reach in and fish out the disgusting creature or just perform the requested errand? Ma had asked me to get meat, not mouse, so the meat was removed, the lid replaced and the mouse left to continue curing. I decided not to tell Ma about the dead mouse, she would insist upon its retrieval. I flunked this moral dilemma, big time.

I retraced my steps, high-stepping my way through the stairway disorder and delivered the meat to Ma in the kitchen without a word.

I didn’t eat any meat that night.

There was nothing like a traveling salesmen to liven things up around the farm. Salesmen representing Watkins and Rawleigh Home Products called every few months. Their merchandise ranged from cleaning supplies to vanilla, nectar (a fruit drink concentrate), pudding mixes, first aid products, fly spray, bag balm for cow’s teats and Cloverleaf salve. We liked the Rawleigh man. He was friendly to kids and his product demonstrations were a good show.

Sitting in the crotch of the big cottonwood tree, we could spot his car coming down the road a mile away, trailing a roll of dust a quarter-mile behind him. The foraging chickens scattered noisily ahead of the car wheels when he turned into our yard.

When Ma heard the car and excited chickens she came out to greet him while wiping her hands on her apron. Sometimes she emerged from the chicken house with a clutched apron bulging with eggs. He followed her into the kitchen with us kids close at his heels. The corner of the kitchen table was cleared for his sample cases and boxes. We hung at his side to see all the stuff.

He gave us all a big smile while his eyes darted quickly about the kitchen for a suitable place to demonstrate his products. A glance at the worn kitchen linoleum told him it was a poor place to exhibit his floor wax. The warped floor boards had caused the linoleum to wear in four-inch parallel intervals that exposed the brick-colored jute base material.

He must have been delighted to see the smoky ceiling above the iron cooking range. It was sooty from the many crumpled newspaper torches used for singeing plucked chickens and smudgy from smoke resulting from many quick sloshes of kerosene on slow-starting fires. He had indeed found the ideal spot to demonstrate a new sponge mop and a granular cleaning product, probably a forerunner of Spic & Span. He dissolved the cleanser in a bucket of water, submerged the mop, squeezed out the excess water and made five long strokes on the dirtiest portion of the ceiling. When the demonstration was complete, there was a three-foot square patch of sparkling ceiling that gleamed like a diamond in that grimy setting. The sale was assured. Ma bought the mop, cleaner, some nectar and a few other items.

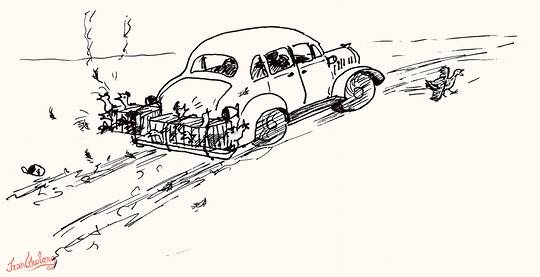

It was time to pay the bill and the bartering of chickens and produce began. Ma snared a few chickens by the leg using a heavy hooked wire. The salesman bound their feet together and laid them on the ground by his car. He took a hook scale from the trunk and hung the flopping chickens by their feet. Once weighed, they knew how many chickens were needed to pay the bill. He untied the legs of the selected chickens and stuffed them along with others already in the wire crates tied to the back bumper of his car. Sometimes Ma traded eggs or tomatoes from the garden. Call it rural collateral.

The salesman bade us all goodbye and drove from the yard in a cloud of dust. Chicken feathers fluttered from the squawking poultry confined in the bumper cages and danced lightly in upward swirls of dust that followed the car to the main road. I already looked forward to his next visit. It was quite a while before Ma got the time and help together to finish cleaning the whole ceiling.

The word ‘turkey’ was not a word of derision to us. Ma raised turkeys to earn extra money for necessities and to make another exciting Christmas possible.

In the spring, the elusive turkey hens would search the weeds, thistles, fence lines and abandoned car bodies for nesting places. Ma hunted for these secluded nests with the tenacity of Sherlock Holmes. She could be seen in her tattered tweed coat, searching the fence lines a quarter-mile away. Sometimes she quietly stalked a turkey hen at a discreet distance hoping to have a hidden nest revealed. Daily, she gathered freshly laid eggs from these nests, always leaving one egg. As long as the nest was not empty the turkey continued to lay her large brown-specked eggs.

The collected turkey, duck and chicken eggs were arranged in flat cardboard boxes cushioned with sawdust. They were in the living room on top the piano, the roll-top desk and the wobbly library table. Each egg was turned daily until it was time to put them under setting hens for hatching.

Turkey chicks were usually raised by a chicken or turkey hen. Occasionally a chicken hen would be given a bunch of duck eggs to hatch and raise. Old Mama hen got plenty concerned when her brood of ducklings went into the pond while she waited at the water’s edge.

Raising turkeys was not without problems. Their roosts were built six feet high so the birds could roost at night safe from marauding fox, coyotes and skunks. One year a nearby farmer sabotaged Ma’s Christmas plans by rustling our turkeys a few days before she was ready to take them to market. She made the toys for us that Christmas. Harvest time for the turkey flock came in November when they were put into crates, and trucked ten miles away to Hecla where they were killed, dressed and weighed. Some years this was done on the farm. The weather was cold. Many plucked, naked, bluish-skinned turkeys, their heads wrapped with newspaper, were suspended by their feet from a wire stretched across the kitchen. They were later packed in barrels and shipped. Freezing them was not a problem, we just set them on the porch for Jack Frost to do the job.

On good years she would have a couple hundred turkeys. I do not know how much money this represented in the l930’s. One November day when I was about twelve years old, Pa was having a bout with his drinking problem. The crated live turkeys were loaded onto the processor’s trucks for the trip to the Hecla buyer. I was told to ride with the trucker to the processing plant where the turkeys would be weighed and a check issued. My only job was to be sure that I got the check, Ma was taking no chances that it would fall into Pa’s hands. I waited and watched through the window in the unheated, drafty little office until the turkeys were processed and the check written. The trucker drove me home.

In November or December Ma would order the Christmas presents from the Sears catalog or maybe get a ride with Aunt Margaret to Aberdeen to do some shopping. Yes, Turkey was King at our house. Ma was pretty special too.

I was well into my fifties in l980 when I found myself seated at a long table with eight other women in a Calligraphy Class at the Palo Alto Art League. Our pens were clamped tensely in our hands, carefully tilted at the specified angle, as we laboriously shaped the letters a, d, g, c, and h. Again and again, we did line after line in endless repetition. It would be unthinkable for us to do any other letter. No, the way you learn calligraphy is a few shapes at a time, repeated hundreds of times with great discipline and deliberation.

My thoughts went back to the country grade school in South Dakota when I was in the second or third grade. Our teacher reserved a period each day for the practice of penmanship. We were guided by the small, red Palmer Penmanship book that required endless repetitions of ovals and zigzag marks of a prescribed height, line after dreary line. This practice enabled students to form beautifully shaped letters, all uniformly slanted. This miserable period of the school day was made doubly-miserable by the spelling class immediately following. The teacher had us write each word twenty times. It was utterly boring, just like the penmanship. My brown, wooden ‘penny pencil’, with the pointed white eraser, longed to dance to the margins of the paper and perform fanciful doodles and drawings. Such interludes were frowned upon. Writing kept us occupied while the teacher taught the other seven grades.

The penmanship and spelling lessons were so disliked that I resorted to a ruse used by children for generations before and after me: I pretended to be ‘sick’. Some days when spelling time came, so did my sudden illness. Clifton Deyo, an older student, would get his horse from the school barn; I would sit ahead of him in the saddle as he took me the l-l/4 miles home. What a lifesaver he was. That day of school was over for me. Once home, my malady miraculously disappeared and I was ready for play when the other kids got home.

So there I sat in my Calligraphy class, fifty years later, halfheartedly forming the tedious line of a’s and o’s across the page, line after line. Some things do NOT improve with age. It was still boring and Clifton was not available with his horse.

Many years after grade school and after doing many hours of Calligraphy for commercial jobs I found that, sure enough, practice does make you improve, a whole lot. I’m also not the great speller that I had considered myself to be and my penmanship is illegible. Teacher was right.

At age eleven, I was destined to become a candy maker. I loved to make candy and excelled at eating this sweet stuff, like chocolate fudge, penuche, taffy, butterscotch caramels, fondant and a few crude attempts at chocolate covered cherries. My siblings didn’t mind eating the candy while it was still warm, the sooner the better. I liked to let it cool so it would cut into nice squares and look nice on a plate that I made a big show of serving. It was an activity where I was the one in control. In a group like ours one had to create their own power base and candy was mine.

One winter night, in order to cool a batch of butterscotch candy quickly, I set the hot candy pan in the nearest snowbank out in the cold darkness. Fluffy, the dog, found the candy and slid the warm pan eight feet across the top of the snowbank leaving paw and teeth marks on the candy’s surface. Such a disappointment. The dog was delighted.

When our cousin from Massachusetts came for a visit, I really overstretched my meager talent in my eagerness to impress. It was a hot summer day and I made chocolate- covered flat mints with a fondant center. Ma suggested that I add a little paraffin (yum) to the chocolate to make it harden. She also supplied a half-walnut to press on top of each piece. Such extravagance, we were out to impress this city cousin for sure. The mints looked terrific, but the chocolate coating remained sticky and needed to be in a cool place. The icebox was full so I took the candy tray to the cool cellar and balanced it on jars of canned vegetables. After a couple hours we discovered that cellar wildlife had struck again. The mice had chewed the nuts on top the chocolates. Their unmistakable claw marks marred the smooth chocolate coating of many pieces. Ma salvaged a few unblemished ones to put on a serving plate.

Candy consumption and lack of dental care took their toll. I got my first job in Bremerton, Washington when I was eighteen and tooth pain forced me to make my very first dental visit. The dentist extracted four badly decayed teeth that very day. A predictable ending to a sweet indulgence.

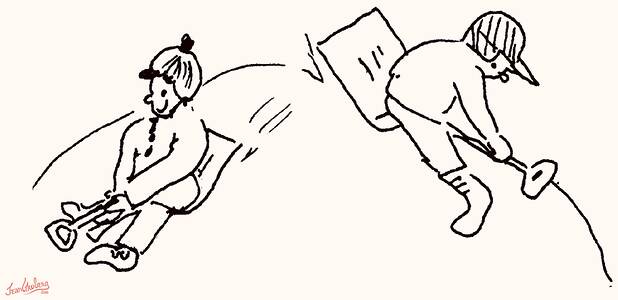

Herding cattle was the most tedious, boring job in the world. It seemed those long, hot afternoons were without end. One summer day two or three of us barefoot kids herded the cattle to an unfenced pasture about two miles away near the Kimball farm. Our job was to watch them as they grazed. It was one of those hot days when the wind was blowing. The pasture was a monotonous plane of grass except for a very small hill. We were grateful for this slight slope that inspired new games involving rolling, somersaulting and sliding. We counted birds, picked little l/4” daisies and buffalo beans, looked for wild strawberries, chased gophers and each other. We did anything to make the time go quickly.

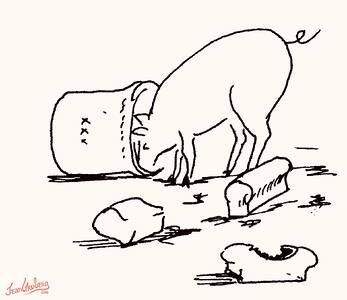

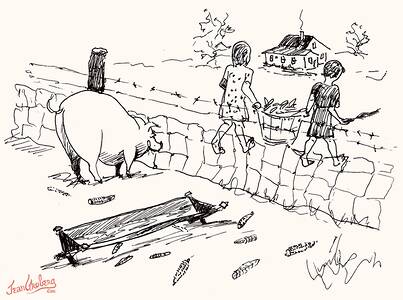

After a few hours in the sunny pasture we decided that a couple of us would go over to Mrs. Kimball’s farmhouse about l/8 mile away and ask for a drink of water. Mrs. Kimball was nice to us and had told us to come get a drink if we needed it. This particular afternoon we were thirsty and went to the kitchen door at the back of the house. There appeared to be no one at home, yet the grunts of full grown hogs sounded from the kitchen. The wooden screen door was wide open and 3 or 4 hogs were snorting about the kitchen shoving loaves of homemade bread across the linoleum with their snouts. It was a mess. The five gallon crock, used to store the bread, rocked back and forth on it’s side as a pig backed out of it.

What were we to do? We had a discussion. If we chased the pigs out and shut the door the unexplained mess might be blamed on innocent Mertz kids who were herding cattle in the area that afternoon. We made our decision, went to the sink, got our drink of water and left the kitchen, leaving pigs and open door as we found them and returned to herding the cows. Perhaps this is the way she wanted it.

Several successive years of drought in the early 1930’s brought on a desperate time. Every windstorm lifted the parched ground and churned the fine particles into clouds that rose several hundred feet into the air. Cyclonic winds pushed this towering gray mass across the prairie like a moving wall. Precious topsoil was blown away and dropped onto fields a hundred miles away. This same relentless wind that sifted and drifted the gray sand, re-sculptured the flat South Dakota landscape. Sand piled into wavy drifts that reduced the height of the four-foot fence posts to twelve inches, sometimes less. It covered fences, inundated ditches along country roads and sometimes swallowed the road itself. The road to school was gradually inched to the ditch as the sand first devoured the fence, the adjoining ditch and then the road itself. The far ditch became our road.

Ma would look up at the sky and comment “There’s no rain in this storm either.” She was usually right. The frequent winds stirred up the dunes in the sandy fields and pelted us with blowing grit. When the sand was blowing, Bruce, Joyce, Verna, Thelma and I wore handkerchiefs tied around our noses and mouths as we walked to school. The handkerchiefs masks became blackened, and moisture around our eyes, nostrils and the corners of our mouths turned into a fine mud outline by the time we got to school. The men came in from the farm yard with mud etched in the creases on their faces.

You could not escape the sand. It was everywhere. The wind forced it through cracks in window jambs depositing little piles of sand on the sill. If the window was open only a crack, a fine deposit of settled on the wood and linoleum floors. Our bare feet carried it into our beds.

We played detective in the dunes that drifted across the road near our house, following and identifying the tracks of various birds, bugs and snakes that had crawled or walked across the wavy sand. We traced the winding trail left by the cutworm. His raised burrow etched the sand for ten feet or more and would abruptly end. There was always a cutworm at the terminus. We would stick a finger in the sand and flip him onto the dune. He would repeat the same behavior, and so did we.

The government made aerial photographs of the devastated farms and from these aerial views learned that land located near tree groves suffered less erosion. The Farm Shelter Belt program was established. Thousands of trees were planted in multiple-rowed strips up to a half-mile long. Once established, they provided the windbreak that allowed the land a chance to stabilize and replenish itself. Today in the 1990’s, groves of trees break what had been a treeless horizon line on the plains of North Eastern South Dakota. Most of todays groves are a result of tree planting programs of the 1930’s.

After many difficult years, the rains returned. The meteorologists of the 1990’s would probably say we had been the victims of an El Niño or La Niña period.

The ‘finger-wave’ hairstyle of the 1930’s was carved into hair that was dampened with slimy homemade wave-setting lotion made from boiled flax seed strained through a cheesecloth. This translucent organic setting lotion kept the waves in place until they dried in crisp ridges.

Helen became quite skilled practicing this technique on the heads of her four younger sisters. A comb in her strong hands dug its sharp edge into our scalps commanding orderly waves. My head would wobble and bobble from the pushing comb. It was not easy for her to finger-wave a moving target.

The invention of the roll bob made new hair styles possible. It had metal tubular jaws shaped like a round clothespin. It grasped wet hair and rolled it tightly to the scalp where it was anchored with a hairpin before the roll bob was slipped out. It resulted in tousled curls and the more modern fluffy hairdos than that provided by finger waving.

We also curled our hair with a scissors-like tubular curling iron with wooden handles. It was heated by suspending it inside the glass chimney of a lighted kerosene lamp. This not only made the iron hot enough to curl hair but it also charred the blue enameled handles. The room reeked of burning hair and scorched paint. If we desired hair curled in washboard- like kinks, the tool to use was our Marcel iron, heated in the same manner. It was a rarely used curler left over from 1920’s hairstyles.

Mom took Joyce and me to the Cosmetology School in Aberdeen to get our first permanent when we were seven and nine years old. Permanent wave machines were cumbersome and primitive. Bunches of hair were pulled through insulated pads that had a steel shield. The protruding hair was wound onto steel rods. The weight of the pads and rods was considerable. My neck got so tired from supporting the weight that I was beginning to yearn for one of Helen’s vigorous finger waves. A little wrench tightly cranked the steel curler rods after which we were connected to a huge electrical contraption with so many dangling electrical cables and clips that it surely must have been borrowed from a prison’s death row. I felt they were going to do us in, for sure. The whole ordeal lasted between three and four hours.

Saturday night was bath night. During the summer we younger ones bathed in a galvanized square washtub placed on the back porch or at the end of the four-plank sidewalk. There was an order in which we went into the water, probably the dirtiest or the least observant one last. Winter bath tubs were usually placed by the kitchen range after supper. As we grew older and wanted a little privacy we moved the tub into the crowded pantry and bathed by the light of a kerosene lamp or lantern. There were not enough towels for all of us, so the well-worn terry towels were reused until they were quite juicy.

We entertained ourselves, using whatever was at hand to make simple toys. We were busy, never bored.

Many activities involved things that rolled. A simple wheeled toy was made from the lid of a gallon syrup pail or coffee can nailed through its center to the end of a three foot lath or stick. We grasped the end of the stick, put the wheel to the ground and ran like the wind. Ah, we were simple folk.

An empty 50-gallon barrel laid on its side brought the repressed circus performer out of everyone. Bare footed, we jumped on those barrels and rolled them all over the farm, frequently in races and sometimes two kids per barrel. The poor man’s chariot, you might say. The ever-so-slight slope in front of the barn was for advanced barrel-rollers only

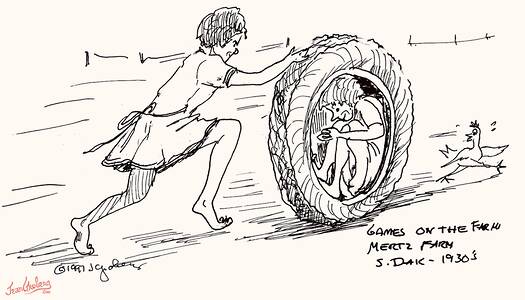

Old tires and inner tubes were rolled like hoops, sometimes with a smaller kid curled up in the empty center hole. A dizzy ride.

Large rusty circular wheel rims from old farm equipment were rolled as a hoop with a pushing stick. Discarded wheels from farm equipment made small carts.

We rolled marbles through arches cut into the edge of a shoe box.

Pa carved wooden shingles into arrows, something he learned at the orphanage. The thin end of the shingle was used for the head of the arrow while the thicker end was carved into a sharp point. It was notched at the balancing point and launched with an upward sling from a knotted string caught in the notch. The arrow landed point down, embedded in the dirt.

He also taught us to make a kite from paper the size of a business letter. He used sewing thread for the string and he flew it skillfully. More complicated kites were made from wooden strips cut from orange crates, string, newspaper and flour-and-water paste. A tail of old cotton rags and several dozen yards of string snitched from Ma’s ball of recycled grocery string and we were off to an afternoon of kite flying.

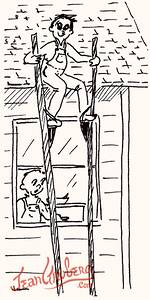

Finding materials for making our own stilts was a matter of scavenging from the wooden storm fence that protected the barnyard animals from cold winter winds. Occasionally the cattle would rub a board loose, although we would sometimes pry off a board for this purpose. The eight-inch boards were too wide for stilts, but one hit with the double-bitted ax split them into two pieces of correct width. Pa’s new, one-inch, black leather harness reins that hung in the machine shop supplied leather straps. More than one piece of leather from the center of new rein was hammered against the anvil until the leather split. Pa was not pleased, if we had taken it off the end it wouldn’t have been so obvious. Beginner stilts were a foot off the ground, the older kids made stilts of heroic three foot heights. They stood on the hay rack to get aboard a tall pair. With the slats clasped tightly to our thighs, we stilt-walked through puddles and indulged in shoving duels attempting to force the other to dismount. One morning Bruce was eating breakfast, he watched with amazement as mysterious long boards moved vertically in front of the kitchen window. Floyd was sitting on top the house attempting to mount newly-built stilts of heroic height.

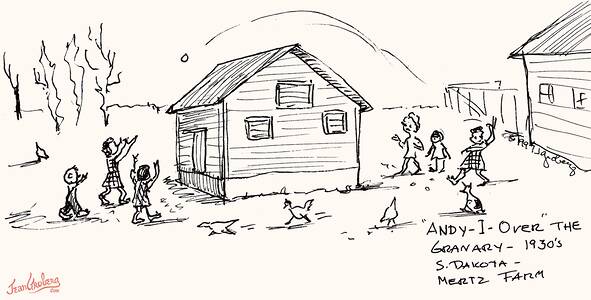

The granary had four interior bins about ten feet deep. Ladder rungs nailed to the interior corridor walls enabled the farmer to climb to the top of the bins to check the depth of the wheat, oats, flax or millet. We liked to climb the ladder and jump, bare feet first, from top of the bins into the grain. Millet and wheat made a smooth landing and the satiny, slippery flax seed was even better. Ma warned that we would break our legs if we jumped into a flax bin that was almost empty. If the flax bin was full, she said we wouldn’t break our legs but would surely smother as we quickly slid into the deep seeds. Obviously she didn’t want us playing in the flax seed and we certainly didn’t want to jump into the scratchy oat bin. The granary was in the center of the yard, free of attached fencing. It was the best place to play Andy-I-Over. We would choose up sides and throw a softball over the roof to the unseen opposing team, a tag game would ensue. Someone once jokingly substituted a rock for the softball. There were no injuries from that particular prank.

The pitched roof of the Machine Shed had a shiny path down the shingles worn by many sliding feet and dragging rear ends . The heels of our shoes made a pleasant ‘click, click’ sound as we slid from one row of shingles to another. It was a fast way to wear out a pair of shoes. We were careful to slide only on the side out of Ma’s view from the house.

Artesian water flowed 24 hours a day into a horse tank made from thick wide boards bolted together. We would climb into the tank despite the mosquito larva in the water and the undulating, long, green slimy fingers of algae at one end. Pa didn’t like us to do this as it riled the horses drinking water.

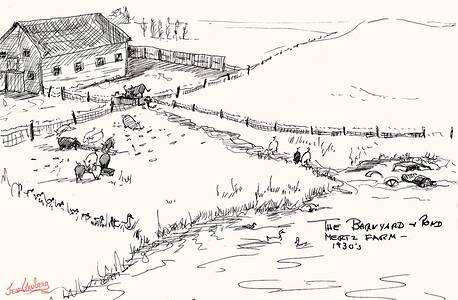

The shallow pond created by tank runoff was over a half-block long and twenty inches deep in some areas. It was not the healthiest place to play, but it was the only body of water for quite a few miles. We weren’t concerned about the assortment of rusted car bodies partially submerged in the water.

During the winter the tank overflow would flow across the hog yard and freeze as it continually trickled down the slope toward the pond. It created a hill of many-layered ice. A few amber discolorations were added by the farm animals that had ventured onto the slippery surface. The icy hill and the frozen pond were favorite winter playgrounds. We used iron skates clamped to the soles of our shoes until Santa gave us black leather hockey shoe skates. We gave each other icy rides on the sled as well as on the steel scoop shovel. Someone sat on the broad shovel, wrapped their legs around the handle and were swung about on the ice to build momentum and were then released, a ride with an unpredictable ending.

One early spring the ice had begun to thaw and it was rubber ice time. It was exciting to cautiously tread the wobbly ice, listen to it crackle under our weight as we hurried across before breaking through. Floyd, our inventive teenage big brother; converted our Flyer sled into a sailing sled by adding a mast with a sail made from an olive colored army blanket. The smaller kids took the first trial rides on this slick sled. The wind billowed that big army blanket and blitzed us swiftly and silently in a wonderful glide over the rubber ice. We sped the length of the pond while Floyd beamed proudly from the shore. After the younger kids had proven the efficiency of his fine design, Floyd was anxious to try a ride. He was fully aware that his additional weight presented a hazard that was not a factor for the smaller kids but was certain the wind velocity would push him so fast that he wouldn’t plummet through the thin ice.

We gathered at the pond edge to watch our adventuresome brother mount his sailing sled. He was Wilbur and Orville Wright all rolled in one, and we were the enthralled audience watching him take this dramatic step into danger. He needed a strong push combined with a vigorous wind gust to assure a safe ride. When a burst of wind arrived, he shouted his orders and we six younger siblings combined all our muscle for an energetic running push-off. Alas! The wonderful momentum created from the enthusiastic shove ran out at the same time the wind gust diminished. The sled slowly slid to a dead stop about 12 feet offshore. The ice sagged ominously and made little crackling noises as we watched with alarm. The secret of success on rubber ice was to keep moving. Floyd was not moving. Unfortunately, the ice below him was.

My sisters and brothers were yelling “Jeannie, go push him, hurry, hurry.” I was selected as his savior either because I was skinny and least likely to cause the ice to collapse or they were too smart to do something so dumb. By the time the shore committee had appointed me, it was too late to help Floyd, for he and his magnificent sled had dropped into the cold water as the sagging ice crumbled. Floyd waded through the icy water to the shore. The magical sled and soggy army blanket were frozen in place until late spring.

One day in late spring, we were surprised to find hundreds of little half-inch toads basking in the warm sun beside the pond. They were piled upon each other three and four deep in loaf-like formations a foot long. There was do doubt that those on the top were getting the most sun while those on the bottom were getting squashed. We watched as a small garter snake crawled out of the weeds in their direction. The toads quickly split from their tight loaf formation, jumped into the pond and swam for their lives. The snake slid onto the pond surface, gliding across the water behind them with his mouth yawning wide. He overtook the fleeing toads, scooping them in his jaws as he swam. We watched as he gulped down four or five toads, like Pac Man. One could count the lumps on his skinny body and know how many toads he had eaten for lunch.

We played work-up baseball on the farm, with a full team right on the premises. One summer evening Floyd, who was sixteen or seventeen years old, was batting fly balls to his six younger siblings. Bruce, five years old, had joined the group in the field. He didn’t stand a chance of getting near the ball in this highly competitive field but he was gamely chattering and waving his arms as Floyd batted balls for different kids to catch. Finally Bruce held his hands together and yelled “Bat me one here, Foydie, bat one here.” Floyd did just that, so precisely that it conked Bruce on the head and knocked him out cold. He was in his little blue overalls, laying unconscious in the dusty farmyard. We were all scared to death and the yard fell into uncharacteristic silence. That was the end of the ball game for that night. Even Floyd was surprised by his accuracy.

Almost every piece of farm machinery had an molded metal seat for the operator. We liked to sit on it. The planting drill had long wooden grain boxes that released seeds into little metal chutes that spilled them onto tilled ground. We played on the long wooden board where the farmer stood when he filled and serviced the seed boxes.

Acrobatic feats of questionable skill were performed on the open framework of hay racks. It was a safe place to watch animals being herded about the farm. As soon as we learned not to spook animals into going the wrong direction we were out there herding them ourselves. We stood safely in the hay rack to watch a conveyor belt connected to a big tractor filled the granary with newly harvested grain.

One summer day we decided to dig a cave. Digging into a hillside was out of the question as our farm was FLAT; our only option was to dig straight down. We went west of the plum trees and dug a beautiful rectangular hole about 5’ x 3’ and 28” to 30” deep. The sides were so nice and straight it looked like an empty dirt box. We laid boards over the top at ground level to form a roof and scooped a crawl-in entry at one end. A little fireplace was carved at the other end and a salvaged piece of galvanized chimney flue carried the smoke up and out. All very scientific. A wad of willow twigs burned so nicely in our little fireplace that we made a trip to the garden, pulled up a potato plant and plucked a few potatoes from the dirt. Just think of it --baked potatoes on our own little fire in our own little cave. How cozy. How nice. We felt we really had something special. So did Pa. He came through the yard and was surprised to see the smoke rising from the flat ground from our cute little chimney. Our cave days were over. He said we could have asphyxiated ourselves and he was right. Our freshly dug cave became the burial spot for a calf that had died the day before. So much for caves and calves.

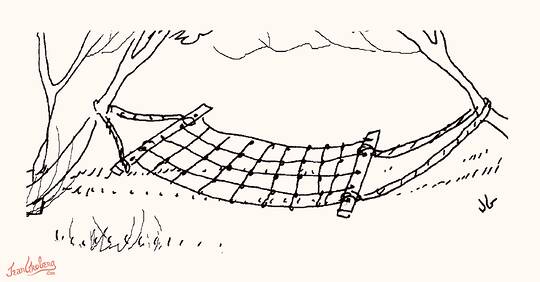

The willow trees west of the house were the perfect place to suspend the crude hammocks we made from pieces of woven wire fencing nailed to wooden 2 x 4’s. Once the harsh wire grid was padded with an old blanket we enjoyed laying and swaying while swinging at gnats and mosquitoes.

By midsummer we were playing hide and seek in the tall ragweed and the attractive stink weed at one end of the hog yard. Pa didn’t want us to hide in the tall cornfield, but sometimes we sneaked into that area also.

Sand burrs and cockleburs were vicious and hooked rides on our bare feet and clothing. Milkweed pods were collected, stuffed with cotton and painted into little birds.

Today it is difficult to visualize living in an isolated place without car or telephone, let alone television. The radio was our contact with the outside world. It was powered by a big black car battery and some large cardboard-covered batteries. Its wires connected under the window sill to an outdoor antenna that ran to the clothesline post. We listened to the Jack Armstrong and Orphan Annie programs after school. Wonderful sound effects augmented a story that flamed our imaginations. Using the foil off the top of an Ovaltine box as collateral, we mailed away for the important secret code badges advertised on the Orphan Annie show. Twenty-five cents and a sponsor’s cereal box top got us a pedometer. The radio was turned off immediately when a specific program finished. We did not waste the batteries.

Every noon Pa came in for dinner and listened to the grain and livestock prices from the trading markets. This was followed by a lively program of peppy Bohemian music, polkas, schottisches and marching music from station WNAX in Yankton, South Dakota.

In the afternoon Ma listened to soap operas; she was a fan of Pepper Young’s Family, Vic and Sade and Oxydol’s Own Ma Perkins. At night we heard Jack Benny, Edgar Bergen, Fred Allen, Major Bowes Amateur Hour, Lux Radio Theater, Graham McNamee’s Do you Want To Be An Actor? and the Manhattan Merry-Go-Round programs.

Saturday night was Hit Parade night and our opportunity to learn the latest songs. We listened carefully and wrote down the lyrics so we could sing songs while doing dishes. We occasionally purchased the Hit Parade Magazine which published lyrics to all the popular songs. We sung right along with the radio’s Hit Parade orchestra.

During the world series Pa chalked a schedule on the big blackboard by the stairway. Ma and Verna tabulated the scores by the inning as they came over the radio. When Pa came in from the field he easily reviewed the game with a glance at the board.

During elections we listened to the hoopla of political conventions. One night when I was a fifth or sixth grade and wanted to hear something besides the Democratic Convention on the radio. Pa wasn’t home and Verna was sitting in his rocking chair. We all knew that whomever sat in Pa’s rocking chair controlled the radio, it was as simple as that.

It was an unwritten rule. Now that is power spelled with a capital ‘P’. The convention was blasting loud and strong. Franklin Roosevelt was the nominee. It was obvious that I wasn’t going to be successful getting the radio program changed to a different station by using charm so I opted for obnoxious. Every time the convention audience cheered and yahooed I joined them exuberantly in a mock display of wild fun. “Yay, Yay!” I shouted, stomped my feet and clapped. I was being as irritable and as noisy as possible with each round of radio applause. Verna rocked to and fro in the rocking chair, taking an occasional sip from the glass of water in her hand. She narrowed her eyes and gave me a couple sideways glances. Ah, at least I was finally getting her attention, -- and perhaps her goat at the same time. She knew what I was up to, and she also knew exactly what to do about it. After five minutes of my rowdy behavior, both the water and the glass came sailing across the room in my direction. It hit the wall behind me. I ducked and shut up; she had made her point. We listened to the convention.

When there are three kids using the same bed who goes to sleep first? Answer: The one who loses the word memory game. These games involved the recitation of a series of related words. The list grew longer as each player, in turn, added a new word to the memory list. After the first forgetful player was eliminated, the remaining two contestants played until there was a decisive winner. The fi nal game degenerated to seeing who could have the last word: “Did,” “Didn’t,” or “Okay,” repeated in turn with long time gaps between. Just when you thought you had enjoyed the last word the other one whispers ‘”didn’t,” and the game was still on. The silences got longer between the lone whispered words until we bored ourselves to sleep.

One afternoon in 1932 or 1933 Thelma and I were in Ma and Pa’s bedroom. I was about eight years old and she was thirteen. She stood before the cracked mirror on their dresser and asked me, “Do you want to see me take out my eye?” Now, not many kids could resist an exhibit such as this, and you could count me among them. I knew it was going to be a memorable occasion as the only tool she had to perform this feat was a wooden toothpick. I was really going to impress my friends when they heard about this.

She had my full attention as I leaned forward on the edge of the bed and urged her to show me. Thelma bent over the dresser, toothpick in her right hand and put her face very close to the mirror. She delicately lifted her left eyelid with her left hand and rolled her eyes toward the ceiling. Her mouth dropped open in a great grimace as she gasped and twisted, her elbow held high. I could see the toothpick making twisting, gauging movements behind her busy hand.

After a minute of this painful dramatic display she triumphantly displayed her shiny gelatinous eye on the end of the toothpick and considerately kept her left eyelid tightly closed over what surely must have been an unsightly cavity. I was one impressed girl, believe me. She carefully replaced the eye in the same fashion that she removed it. Years later, I concluded I had been the victim of the old skinned Concord grape caper.

Someone gave us a wind-up console style phonograph and a big stack of records. Where else could you learn such songs as When it’s Peach Picking Time in Delaware and Carolina In the Mornin’, sung fast or slow, depending on how tightly the phonograph was wound?

By carefully stepping on the boards stretched across the 2 x 4 studs in the attic we could reach an old zither, an accordion and Floyd’s old Hawaiian guitar. A misstep, and your foot would dent the lath and plaster ceilings of the two rooms below. The attic was a good place to hide, to sit by the little square window overlooking the yard below and imagine everybody was looking for YOU. In most cases, they weren’t.

Helen could sit at the piano with the Sears Roebuck Catalog on the music rack. She read the titles of the popular sheet music available and played each song by ear. Our piano was repossessed. Someone gave us a pump organ, It was a race to get home to be first to play the organ. The last quarter-mile walk from school was more like a run. Verna could play Work For the Night Is Coming quite well, and often. When I was in eighth grade another piano appeared and it was around for several years.

We liked school so much we played ‘school’ on the open stairway. The steps were convenient recitation benches and the teacher of the day directed the learning activities from the big blackboard, with a broken corner, mounted on the wall at the bottom stair landing.

During the summer we burned corncobs in the kitchen range. After throwing the empty apple basket over the wire pig yard fence we began the messy job of gathering the corncobs that remained after pigs had chewed off the kernels. Barefoot, we stepped carefully, avoiding sharp rocks, rusty nails and slivered boards. Some cobs were muddy and some had fallen on hidden piles of manure. We avoided stepping in some of these nasty surprises with our bare feet. The job turned into a bit of fun if we found tail and wing feathers from roosters and turkeys that we inserted into the ends of broken cobs. Grasping the feather, we threw it high into the air and watched it slowly twirl toward the ground, cob first. After the fun, we carried the cob basket to the kitchen and set it by the stove.

Bang! Bang! and Whop! Pa stood at the top stairway landing, ignited a large firecracker from his lighted pipe and tossed it under Floyd and Howard’s bed. With a thundering ‘BANG’, rolls of dust, feathers and firecracker smoke billowed from under the bed. Floyd’s eyes flew open. Another 4th of July in the early 1930’s was off to an explosive beginning.

We stayed home on many July 4ths. A big bag of fireworks was divided amongst us and we could light our own firecrackers when we wished. Later in the day we usually made two gallons of ice cream in the hand-cranked ice cream freezer.

Floyd and the older kids were creative with fireworks. Some firecrackers were ignited under empty tin cans that flew high into the air. The deep thumping noise of a firecracker exploding in a topless fifty-gallon metal barrel thrilled us all. By the time Ma came to check on an explosion it was too late for her to do anything but caution us.

One holiday I stood on the plank sidewalk with my allotment of red cellophane packets of 2” firecrackers. The farmyard sounded as if a military battle was taking place. The punks were all gone so it was time to make our own from the glowing cardboard casing of a spent firecracker. On this particular day I made the biggest punk of all by just pulling out the wick of a firecracker and lit several firecrackers from the glowing casing. Why bother with a half-punk, I thought.

Suddenly all hell broke loose. The punk exploded in my hand. Pa came thumping onto the porch. He grabbed the brown bag of firecrackers from my hand. “Those God damn firecrackers,” he shouted. His expletives were the most colorful pyrotechnics in the farm yard. My firecrackers were gone. I didn’t mind. I would help light the Roman candles after dark.

We frequently would see the towel-covered dishpan full of bread dough left to rise on the table. While waiting for the bread to rise Ma would pick up a milk pail and walk down the path to the garden to pick vegetables. We would watch until she disappeared behind the machine shed.

It was a scenario made for mischief: Ma was gone and the dough was defenseless. We pinched off walnut sized pieces of dough. It quickly became grimy from the grit on our hands. At the count of three, we tossed the gray-colored dough balls straight up. Smack! They hit the ceiling and stuck. Standing below, we watched them elongate as gravity eased them away from the ceiling and they eventually dropped into our waiting hands. Whoever owned the first falling dough ball was the winner. We threw them up repeatedly, always catching them as they fell. Some dough residue remained on the ceiling, joining many textured bits remaining from previous games. Some days the dough balls were tacky and slow to fall.

Such a nice game, no quarrels, we threw dough balls until someone saw Ma returning with the milk pail full and her apron bulged with tomatoes.

“Here comes Ma,” we whispered as we quickly swept the balls from ceiling using the kitchen broom. We caught them, replaced the towel on the bread dough and ran to the back porch to greet Ma. She was pleased to see the cob basket filled. Such obedient angels.

Flies were a persistent problem on the farm. We occasionally sprayed indoors using a hand operated push- sprayer. It coated everything with a foul smelling oily residue, but it did the job. A few minutes after the spray application, we would enter the room and sweep dead insects from the windowsills and floor. Mom did her best to prevent these pests. There were tattered strips of an old green window shade nailed to the top of the screen door. It was hoped their fluttering would scare flies away. Our screen door was opened a lot and the many kids added to the problem by taking screen door rides. We would dig our bare toes into the bottom screen door molding, grab the handle and push off for a slow ride. Several dozen grateful flies flew into the house with each swing. On warm summer days, particularly, if the air was still, there would be a couple hundred flies clinging to the outside of the screen awaiting an opportunity to enter.

Sometimes, it was necessary to herd flies by waving towels. We were skilled fly herders. Several of us, with a towel in each hand, began the pursuit in Ma and Pa’s bedroom. With wildly waving towels we scared flies off the window panes and immediately pulled down the shades. Like a Revolutionary War martial column we started in the far corner of the room, waving our towels, floor to ceiling, systematically advancing on the enemies. We forced them to fly through the doorway into the living room and immediately closed the bedroom door. The same procedure was used in the living room. The towels flapped in big vertical sweeps. Our little army followed the established battle plan swishing the flies through the dining room and into the kitchen, always shutting doors behind us. By this time we were not dealing with just a mere hundred little flies, there were thousands. We confined them in the entrance hallway near the back door and took the whole bunch prisoners. Their buzzing was like that of a million little chain saws. If fly spray had been available, they would have been annihilated on the spot. None of that Geneva Convention stuff. If there was no fly spray available, our next move was to chase them outside. Bruce, the littlest, had the distasteful task of holding the screen door open as we shooed the flies out of the house. He wrinkled his nose, shut his eyes tightly and pursed his lips shut as the flies pelted by, hurried by five pairs of frantically waving towels.

The last two rooms sometimes needed additional chase- throughs to eradicate stragglers. The back door was then closed and we stayed in and enjoyed the fly-free house. The flies clung to the outside of the screen door awaiting an opportunity to return.

On hot July nights in the 1920’s and early 1930’s, the only air moving on our farm was that displaced by the whirring wings of l,000,000 annoying mosquitoes. Their shrill, ear- piercing whine vibrated the air. In the barnyard, they agitated the cattle and made them restless. Pa and the older boys threw damp weeds on a small barnyard bonfire. The dense layers of smoke drifted slowly about the animals protecting them from the flying hordes.

To sleep outdoors was to offer yourself as a human sacrifice to the mosquitoes. We usually opted for the ritual of moving bedrolls about the house on hot nights, looking for a cooler place to sleep than the place we had just left. After the house quieted down for the night, one could hear the scraping sound made by the legs of iron beds being dragged across floors in the upstairs bedrooms as kids vied for a prime sleeping place near the window.

On these sultry nights four or five of us moved our blankets to the floor in front of the living room screen door to catch a possible southerly breeze. We plumped our pillows and began a session of giggling, tickling, and arguing until each found his or her ‘place’ on the blanket. A well placed pinch was the weapon of the smaller kids; but this was no match to a vise-like grip on the quadriceps muscle above the knee when administered by one of the older kids. We were intent of having fun for a while and played memory word games. Anyone that couldn’t remember the list of words in proper order had to drop out. When one or two kids dropped off to sleep, draping their arms and legs all over the place, the spot on the floor wasn’t much fun any more.

The news that a breeze might be coming in the dining room window would cause more than one person to grab their pillow and hurry that direction. An instant bed was created by bridging the distance between two chair seats using the legless ironing board. Sure, it was a very narrow bed, but it was a cooler one.

One night the sultry air drove Pa, wearing his white BVD’s, out of their bedroom. He dragged his blanket into the dining room and placed it on the long, fully extended, dining room table. He climbed gingerly onto the table and laid down, forgetting that the table extensions were missing a number of the securing pegs. Before long, the extensions buckled, tipping table leaves to the left and the right. Pa was dumped onto the floor with a terrible noise of falling boards and body which was followed immediately by a barrage of profanity. The tragic spectacle was also wildly funny to little kids and we put our faces in the pillows from our beds on the floor and suppressed a giggle. We were all so glad he didn’t hurt himself.

One year when I was about 8 or 9 years old, probably 1933 or 1934, there were lots of potato bugs on the potato vines. Pa said he would pay me 75 cents if I would fill a bucket with potato bugs. He was probably teasing, but I took it seriously. Seventy five cents! What an opportunity! I knew instantly that I was on the verge of making my fortune in the potato bug market. One summer morning I carried a two-gallon pail to the patch and began the task early. A long time went by, something like two-hundred years, and I had hardly collected enough bugs to cover the bottom of the bucket. I realized it would take me all day, perhaps longer, to fill the bucket so I opted for early retirement and saved Pa seventy-five cents. I would have to make my fortune elsewhere.

During the 1930’s the Striped, Flicker Tail and Pocket Gophers damaged farmers crops in our corner of South Dakota. To encourage their eradication, the township officials paid a bounty of two to ten cents per gopher tail, depending on the species.

We kept busy during the summer months setting metal traps at gopher holes in our cow pasture and along ditches, marking the location with a two-foot anchoring stake. Sometimes we caught more than one gopher from the same hole. One time I was checking the trap line alone. There was a weasel in our trap. He is a feisty little animal belonging to the ferret family. He was so strong that he lifted the metal trap off the ground as he lunged at me, his body arching, mouth open, teeth bared. I was scared of this nasty little fellow and left it there for one of the older kids to take care of.

Pocket gophers were more difficult to catch but also more profitable. A bounty of 10 to 20 cents was paid for a pair of front claws. We would scrape through piles of fresh dirt mounds looking for their holes so we could set a trap. The older kids were more successful. The collected claws and gopher tails were stored in the Prince Albert tobacco tin. We each kept careful records of how many tails in the tin were ours. When the tails were redeemed at the township board. The money was carefully disbursed.

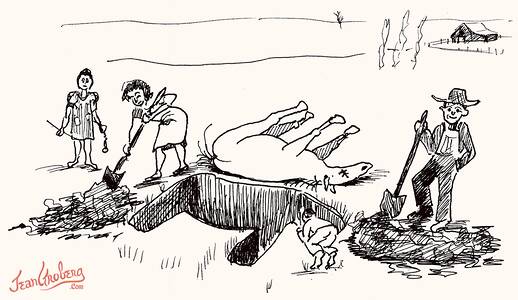

While checking the trap line in our pasture one summer afternoon I came upon Floyd and Helen, ages 14 and 15, digging a grave. Old Bill, one of the favored work horses was stretched out stiff on the ground. They dug a unique grave. To save a lot of digging they dug a horse shaped hole right along side of old Bill’s back. They planned to flip him over and let him drop into this custom designed hole. My sister and I watched while they put in a grave marker.

A bounty was paid for skunks, coyotes and badgers. The older boys scraped and stretched these pelts on flat boards and leaned them against the fence during cold weather.

County roads divided the flat countryside into a square mile grid. One winter the farmers organized a hunt to eradicate jackrabbits. They dressed warmly in twill sheepskin- lined jackets, their ears protected by the flaps on their brightly colored plaid caps. They marched across the cornfield like the forward line of a military regiment. Their four-buckle rubber overshoes made crunchy noises in the dry snow. We younger ones watched from the living room window as the men marched across the field, an evenly-spaced human wall flushing and shooting the rabbits. When the hunt was over, a huge pile of dead jackrabbits was loaded onto a bobsled. The hunters celebrated their successful hunt with a oyster stew served at the Pool Hall in Houghton. Someone brought home some of the leftover oyster stew.

Baby cottontail rabbits would get in the way of the plowshare during spring plowing. Our father and big brothers stopped the horses, got off the plow to catch the bunnies and put them in their jacket pockets. The bunnies were awfully cute, scarcely bigger than the palms of our hands and not afraid of us. We let them run around the house and fed them milk out of a saucer. They were later returned to the field, if they hadn’t already escaped or fallen victim to a cat, dog or clumsy kid.

The sharp call of a pheasant was a pleasant evening sound when they were abundant in the 1920’s and 1930’s. We found their nests, filled with small gray-green eggs, hidden in the fields and under tumbleweeds in the spring. Once hatched, the chicks were fast on their feet and the wary hen kept them hidden in the tall grass and weeds.

Hunters from other states came during the autumn hunting season. They frequently knocked on our door seeking permission to hunt the pheasants in our fields of wheat stubble and corn stalks. They would then drive their car as close to the field as possible. Sometimes as they drove off our land they would leave a few dead game birds on our porch as a gesture of appreciation. This probably also took care of a potential problem if they had exceeded their limit.

During hunting season our 1 1/4 mile walk to school was a continual hunt for the discarded brightly colored, brass-tipped shotgun shells. We collected and traded them. The collections gradually disappeared, probably scattered around the farm yard.

Ma usually skinned and fried pheasants, serving them in a cream gravy. Some were canned for later consumption. We poked the long tail feathers into the holes of a 2” wide strip of a corrugated cardboard box and make Indian headbands. Corncob stubs were pierced with long tail feathers from pheasants and turkeys and then flung high into the air.

Bruce was only five and he knew what to do with a well- trained dog like Fluffy. He was home alone with Ma while we older ones were at school. She was inside taking a few minutes to sit down and read before we came home from school. Bruce wandered in and asked her if she wanted some chickens for supper. She was reading and not really listening to him, and murmured an affirmative “mmm hmmm”. This was often her answer if she was thinking about something else. That was as close to ‘yes’ as Bruce needed and a short time later he laid eight dead chickens on the porch. He was indiscriminate in selecting the chickens for Fluffy to ‘get’ and there were laying hens among the killed birds. That night Pa helped Ma pluck and clean these chickens on the back porch. Joyce and I watched as he cut into the hen and removed small developing eggs and showed them to us. Joyce, about 7, poetically commented “Oh, those are the hearts of youth” and Pa laughed until tears rolled down his cheeks.

When spring came, Ma pursued the duck hens like she did the turkey hens, collecting the eggs from their nests and laying them in boxes of sawdust alongside the turkey eggs.

For a few years there was a big table-type incubator in our dining room. It was heated by a kerosene burner. The collected eggs were spread on incubator trays that slid out for daily turning and a sprinkling with moisture. How lucky we were to see hundreds of little chicks, turkeys and ducks and occasional pheasants fighting there way out of the egg shell right next to our dining room table.

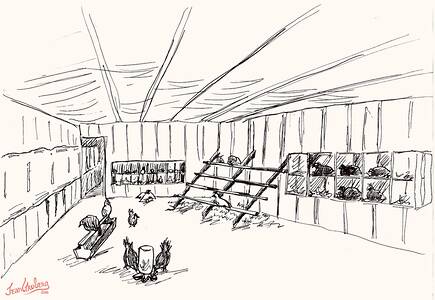

Ma had chickens in all colors: snow white Leghorns, gray heavy-bodied Plymouth Rocks, Rhode Island Reds, the brownish Buff Orphingtons and even a Wyandotte or two. They provided us with lots of eggs and meat. They roamed the farm scratching up seeds and fluffed themselves in dust baths while freely squirting their excrement everywhere. We learned to be very careful where we stepped with bare feet.

The chicken house was awful to enter, particularly if one liked to breathe real air. There seemed to be no oxygen in this stifling room. In the winter it was suffocating. Its low ceiling was stuffed with straw insulation and the windows were covered with opaque screen fabric. Tightly shut doors blocked the bitter cold and the chickens did not venture from the building. No need for that, for we carried food and water to them. The smell of chicken manure was strong and the feathers and dust were constantly stirred by the flapping wings of bickering, active chickens. Squabbling sparrows spent their winter with the chickens, enjoying the same protection, water and feed. Once a day we gathered eggs from the double rows of nesting boxes on the walls. As soon as a hen laid an egg, she stepped out of the nest and noisily broadcast the news of her accomplishment. Those were the easy eggs to collect. I tried to do the whole egg gathering with the one deep breath that I took before entering the building. I hurriedly snatched eggs and left before breathing again. Setting hens never laid any eggs. Their ambition was to be a mother and hatch those eggs. She fought to keep the eggs under her. Any defensive setting hen sitting possessively on a nest of freshly laid eggs severely impeded my progress and she didn’t mind delivering a few sharp pecks when I reached under her to take an egg. When the warmer months arrived, we cleaned the chicken house and painted the roosts with a solution to kill mite infestation.

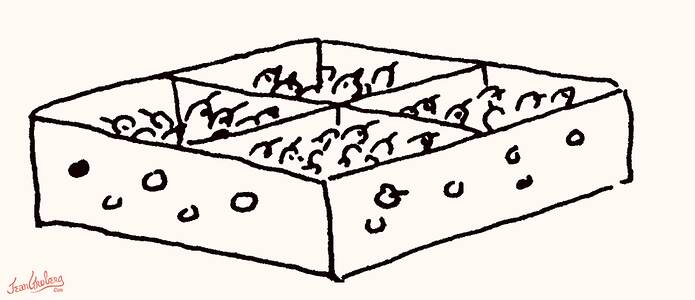

Some years chicks were ordered from a hatchery. They were delivered in the spring to the General Store in Houghton. Boxes of peeping chicks were stacked five feet high in the back of the store awaiting pickup by the farmers. The 30” square boxes were divided into quarters, with 25 chicks in each compartment. One peek into the penny-size air holes in the sides of the boxes would put us eyeball to eyeball with a little yellow chick who gladly pecked an offered fingertip.

Once taken to the farm, the chicks were assigned to those grateful setting hens who guided their young charges through the farmyard in the daytime. When evening came, the hens fluffed their feathers and spread their generous wings to provide a wide protective covering for the chicks.

Fried spring chicken became the noon meal of choice when the chickens reached edible size. ‘Free range chicken’ was the only kind of chicken we knew. Ma had a couple ways to catch a chicken for dinner. She threw chicken feed on the ground. While the chickens nibbled, she would let one of us kids creep behind and snag a chicken’s leg with a four foot hooked wire. For a few years we had a well trained dog called Fluffy who would catch any chicken you designated. If you said, “Get ‘em Fluffy”, Fluffy “got ‘em”.

Ma wrung a chicken’s neck by grabbing its head and twirling the body in a circle until it separated from the head. We watched in awe as the headless chicken jumped about until it flopped over and died. It was then dunked in a bucket of boiling water to make the feathers pull more easily. Any remaining pin feathers were singed by a newspaper torch held over an open lid on the kitchen range. The ceiling showed the sooty signs of this activity. We all learned to eviscerate poultry.

One morning Ma caught some chickens for dinner and showed me how to wring their necks. It looked so simple with Ma’s instructions: “Take the chicken’s head in your hand and twirl its body around like a jump rope.” Sure. Ma had already wrung one head off, and stood there with a rooster’s head in her hand as the headless body hopped about in the dust. I determinedly seized a doomed chicken’s head and flopped its body into circular twirls as directed. I was not strong and the weight of the bird made my arm drop downward. This gave the chicken an opportunity to reverse the spin I had put on it’s neck. It promptly unwound and gave its wings a couple flops. His kicking claws scratched my bare legs and I released him. He ran in a frenzy across the yard to get away from his potential killer and live another day. I flunked chicken killing.

When Ma predicted a storm she was usually right. When clouds popped up over the horizon this weather wizard knew from the direction of the wind if we would get rain, and she knew when it was ‘over’. She did this without the help of weather satellites or television for she had her own system. She claimed that, “If the sun went down (set) behind a cloud on Friday it would rain before Monday.” “If there is enough blue in the sky to mend a pair of men’s pants it means there will be good weather tomorrow. The taller the cumulus clouds, the bigger the hail stones.” She would sniff the air and say, “They got hail somewhere.”

She would occasionally refresh our fears of the storms with a new tale of some terrible thing that happened to someone in the community during a storm. Many of these tragic events had occurred twenty or thirty years previously, but their lesson value was not diminished. Her vast collection of these horror tales were used to teach us caution, and some of her stories were awesome. No one ever “cut their head”, in her vernacular they “split their head open”. A warning to keep something away from our face was worded. “You’re going to poke your eye out!” A wrestling tussle would bring forth “You’ll rip your arm out of the socket!”. She always emphasized the verb.. She may have been graphic, but she was also smart. If you are raising ten kids, have no car and are twenty to forty miles from a Doctor, you scare the kids enough so they won’t do anything stupid and hurt themselves. She was skillful at wording things in a way that caught our attention.

When a storm threatened, it was an important to disconnect the wire connecting the battery-powered radio to the outside antenna. We would then quickly chase chickens into the chicken house and hurried the ducks from the pond by throwing a few corncobs into the water. The duck hens waddled through the tall grass, single file, followed by tumbling ducklings, spilling and rolling through the grass as fast as their little legs would go, The turkey broods were shut into their coops. A sudden storm hit one late afternoon when we were not prepared. It was a dramatic symphony of lightning, thunder, rain and wind with a finale of good- sized hail. The little ducks and turkeys that weren’t under shelter stood in the rain facing the storm. A few were knocked over by hailstones. Afterwards, when the sun highlighted a rainbow arched across the dark afternoon sky, we were sent out to bring in the wounded and drowning young turkeys, ducklings and chicks. Ma was right there wearing her kitchen apron, the indispensable farm woman’s garment. She pinched the hem together and the apron became a basket for young wet poultry that she carried to the kitchen. Their soggy limp bodies, feathers matted with water, were laid on towels on the lowered warm oven door with hope that some of them would revive. A lot of them did.

We would go out after hailstorms and scoop up handfuls of the pellets into icy balls. As the old saying goes, “When life hands you a lemon, you make lemonade--.” but a few times when life handed us a lot of hail, we made use of that free crushed ice. We brought out the ice cream freezer and made two gallons of ice cream before the hail melted.

The lightning storms were dramatic and had a way of demanding ones immediate attention. During the night the bolts of lightning slashed through the cracked green fabric window shades knifing instant light into the room. Floyd told us how to count time between the clap of thunder and the bolt of lightning to determine how close the lightning was striking. Counting up to 7 or 8 meant it was not striking very close and I was out of danger, at least from that last bolt, which was all I cared about. As I grew older I got wiser, and Floyd, who was the most wise of all, told us that rubber would not conduct electricity. This was the most welcome storm information that I had ever heard and after that, during lightning storms, I carried a flat, red, canning jar rubber about 4” in diameter and achieved full immunity from lightning strikes. I tempted fate joyfully, venturing into puddles knowing the rubber ring clutched tightly in my hand was performing its repellent magic. I carried it when we were out putting chicks and ducks into their shelters before and during electrical storms. It was always in my hand when I made a trip to our outside toilet. I never got struck by lightning while carrying it.

We also learned from our wise older brothers and sisters that you shouldn’t stand near a tall tree as they ‘drew’ lightning . God forbid that the dog come near at these critical times as we had also been told that dogs ‘drew’ lightning. Dogs never got any comfort from me during a storm. Occasionally some farmer would lose cows that had been standing near a woven wire fence when lightning struck the fence. Floyd forgot to tell us that cows ‘drew’ lightning too.

We knew Christmas was not far away when the red and green paper ropes were draped diagonally across the living room ceiling. A collapsible, red, tissue paper bell dangled at the intersecting point. A few times we had a Christmas tree and decorated it with foil icicles and ornaments.

We were careful not to enter the closet in our parent’s bedroom during December because we knew the presents were hidden here. One year the infamous candy underground organization spread the news of the existence of a big brown bag filled with hard zig-zag ribbon candy. It diminished in volume considerably before the holiday. Even during the depression we had a nice Christmas. When there wasn’t turkey money, Ma made things.

On Christmas Eve we unfastened the elastic supporters from our long winter stockings, peeled them from our legs and hung them up, still warm, at our preselected spot. The older teenage boys participated at a less serious level. They hung their long winter underwear, legs knotted at the ankles, as ‘stockings’ to receive Santa’s gifts. Usually some oranges and nuts were shoved into our socks. As a joke, Santa occasionally tucked in a coal briquette along with the fruit in the boys long underwear.

One Christmas eve we looked out our living room window, and standing out there in the dark was Santa Claus. His red costume reflected the light from the gas lamp sitting on the library table. He shook his finger at us and disappeared into the night. We quickly went off to bed. Years later we learned Ma had borrowed the Santa costume and put in on in the barn by the light of the barn lantern. The older boys were out there doing the evening milking at the time and also had a little fun. When Santa shook her finger at them, they squirted her with milk from a well-aimed udder. Good shot. Even Santa didn’t get respect from those guys.

On Christmas Eve, Pa sat in front of the radio until late at night listening to Christmas carols and other holiday programs. He sometimes wept, it was hard to tell if he was happy or sad. Beginning at age three, he spent thirteen childhood years in a Catholic orphanage. Perhaps he was wondering where his three brothers and two sisters were. This always seemed a sad night for him. Whenever he walked into a room where two of us kids were fighting he always took us aside and told us how lucky we were to be together and that we shouldn’t quarrel.

One Christmas Eve Santa mixed up the gifts. On Christmas morning Joyce became immediately attached to the huge doll by her stocking. It had a sawdust-stuffed body, opening fluttering eyes and pink rubber pants, Ma realized Santa’s mistake and switched the dolls in front of us on Christmas morning. I was then given the large doll that Joyce had just fallen for. Joyce was given a smaller molded rubber doll. I wasn’t particularly fascinated with dolls, but Joyce would have loved that big doll. Hers was obviously not as nice as mine and she was in tears. Pa thought a bit of fun would change tears into smiles and secretly put a little French’s yellow mustard in my doll’s rubber pants. He sat his rocking chair pretending to read while he waited to see what my reaction would be. Of course I was quite amazed. Joyce wasn’t amazed or amused. She was still cross.