This Is Your Life - Part II

One autumn night after finishing the dishes we hurried to the front room to play games near the brighter gas lamp. We balanced the wooden game board on our knees and dealt out the cards for a game of 500 Rummy.

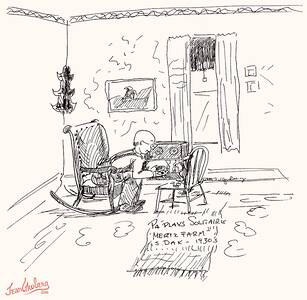

Pa was already in his rocking chair with the flattened rockers. A print of the Remington Indian painting “End of the Trail” hung on the wall behind him. Ma sat in her smaller wooden rocking chair reading a magazine. She was wearing one of the striped, buttoned-up-the-front house dresses that Pa would occasionally buy for her. He always bought her striped dresses and in later years she stated she never cared for stripes or dresses that buttoned up the front. The two lowest skirt buttons always popped off when she placed the milk pail between her knees while milking cows. Pa had gone somewhere that day and had come home with too much to drink. When he was sober his speech was well- peppered with ‘Goddams,’ but when drinking his language elevated to that of an English professor, flowery and multi- syllable words flowed freely. Growing up in an orphanage may not have provided him with a good education, but he had a keen interest in learning. During the winter we would bring home one encyclopedia after another from school for him to read from cover to cover. He read our large library-size dictionary like a non-fiction book. His remarkable vocabulary was used mainly if he had been drinking.

On one particular night Pa was intermittently nodding off in his chair and talking to Mom in exquisite detail and in a most scholarly language. Year by year, the story poured forth, the story of their life together, year by year. Ma filled in the gaps in his recantation with an occasional “Mm hmmm,” as she continued to read her True Story magazine.

I listened as Pa trolled out the saga of the Mertz family and how it grew. After 45 minutes he was now saying “and as time passed, little Floydie was born,” he was only as far as Birth #4 out of 10 kids and he was telling it in chronological order. It was obviously going to be a longer story than usual and it would be another half hour before he would get to the part most interesting to us: the story of births #7,#8, #9 and #10, OUR births. We had heard this tale before, it was a long one and we already knew the ending.

We tallied the game score, leaned the game board against the wall and went to bed.

The older children remember the loving, playful father who made merry-go-rounds, kites, played games and enjoyed a practical joke. A father who served on the school board and who loved to sing, singing occasionally with an informal men’s quartet in town. He encouraged his children to sing. A father with time for the children. A healthy, hard-working man, well loved by the community. We younger ones knew that fine, generous man was in there somewhere, we just didn’t see him as often as the older siblings.

Several cottonwood trees, a half-dozen willows, another half-dozen plum trees and ten or twelve scraggly poplars north of the barn supplied a limited amount of fuel. The winds blew down dead twigs and branches that we burned in the kitchen range. We collected corncobs after the pigs had chewed off the corn. Sometimes a delivery of wood was dumped on the ground by the ice house, much of it in need of splitting. Even the very youngest of us could split wood using either the single or double bitted axe. We knew how to pound the handle on the ground to tighten loose bits; after three or four chops the axe head would loosen and require the same adjustment.

One summer we burned cow chips, hardened dried discs of cow manure, that we picked up in the pasture. Another year, when corn prices dropped to three to five cents per bushel, our crop of ear corn was burned as kitchen stove fuel.

In the fall Pa and the older boys drove horse-drawn wagons bringing loads of lignite, anthracite or briquette coal from the Houghton elevator four miles away. It was shoveled into a metal chute jutting through the cellar window and made great clanging noises as it bounced down the chute and onto the cement floor of the coal bin.

The foundation of the house was banked for winter. Pink- toned tar paper was wrapped completely around the house foundation up to three feet high. Nailed lath strips held it in place. The job was finished off with many loads of barn manure piled 14” high against the pink tar paper completely around the foundation. This manure insulation prevented potatoes and jars of canned food from freezing in the cellar during freezing temperatures.

Fire in the front room stove was banked at bedtime so it burned very slowly overnight. It was reactivated in the morning with a vigorous poking followed by a scuttle of coal. We were glad to come down from the frigid upstairs bedrooms to warm our clothes and dress behind the stove. Those who were advance planners warmed their mittens here and had cozy hands on the way to school.

As sure as the sun rose in the east, you could count on Ma frying pancakes for breakfast. She presided over a blackened 18”” round griddle, baking pancakes, five at a time, while the family ate. Finished cakes were flipped onto a rapidly disappearing stack in the center of the table. They were served with fried eggs, sausage, butter, various homemade jams, and cold, brown Karo corn syrup that was purchased in one-gallon or half-gallon buckets. We didn’t waste drop of the thin gravy made from browned sausage drippings.

We sometimes had cold cereal in the summertime. Milk was plentiful and the sausage was all gone. Stale bread dipped into an egg mixture made French toast.

White bread dough was mixed in large quantities in an enamel dishpan or wooden butter bowl. The bowl was covered with a clean dishtowel and the dough left to rise. The dough was shaped into loaves and placed in well-blackened pans holding three loaves each. She baked nine or more loaves at a time.

Corncobs were burned to heat the oven. Even though it was missing a thermometer, Ma knew when the oven was hot enough for baking just by thrusting her hand into the oven. A murmured, “Hot enough”, a nod, a smile and the loaves were put in to bake. Our job was to keep the corncob baskets filled. About 45 minutes and a basket or two of corncobs later, she peeled apart two hot loaves and dented the exposed surface with her fingertip. If the dent popped back up, the bread was done. It was stored in a five-gallon crock covered with a large enameled lid. Another crock, the same size, stored white flour which we purchased in one-hundred pound bags. The flour crock was covered with an inverted enameled dishpan. The crocks set side-by-side on the pantry floor.

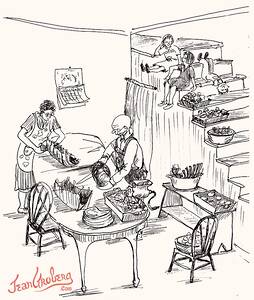

Butchering was a messy, difficult task that consumed a lot of time and space. We would climb in the hay rack and watch as the men killed, scraped and cleaned the animal. It was hung by its back feet on a singletree outside the granary window. The large meat quarters were carried to the oilcloth- covered dining room table and cut into usable sizes.

Since there was no stair banister on our stairway, the open steps became convenient shelves for the meat cutting operation. They were also good viewing seats for little kids. If we got bored watching the meat operation, we slid down the steps on our bellies or on our behinds, head first, or feet first.

A hand-cranked sausage grinder turned out many pounds of homemade sausage. The white pork fat was cut into one- inch cubes, tumbled into wide, deep pans and heated in the oven. The cubes simmered, releasing liquid lard and leaving each cube an empty amber shell. The pan was then emptied into a metal lard press which operated like a grape press. A metal plate placed on top of the rendered fat cubes was compressed downward by the turn of a huge screw. Clear melted lard dripped into a container below. The disc of solids remaining after the pressing was used as shortening for making crackling cookies. They fried pork chops in great quantities, layered them in gallon jars and poured hot melted lard over all. The lid was screwed in place and the canning was complete, no further processing was needed. These jars were stored in the cool basement with other canned goods. Some of the pork was cured into bacon but the larger chunks of meat were submerged in a salt brine in two twenty-gallon crocks in our cellar. When the salt pork was boiled, it was pink and tasted like ham.

Ma saved seeds each fall by squirting ripe tomatoes onto newspapers. In late winter she planted them indoors in flat wooden boxes, usually old peach crates that had been lined with newspapers. She created metal planting boxes by tin- snipping away one- half of rectangular, gallon cans from the gas station. The planted seed boxes were covered with a newspaper and placed in the living room on the desk and the waltzing library table. Here they were nurtured until after the spring thaws. She watched the moon and never planted seeds in the ‘dark’ of the moon. Seeds planted at the wrong time would become leggy. As the plants grew, she discarded the spindly and saved the strongest. She waited for warmer weather and a plowed garden.

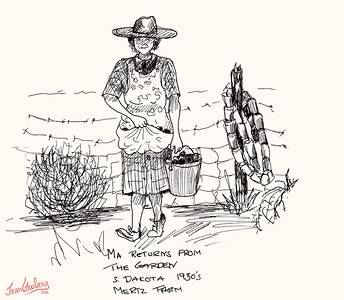

The vegetable garden was about three city blocks away from the house. Every spring when horses were hitched to the plow for field work, the garden was also plowed. A horse- drawn manure spreader scattered barn manure over the fields and garden. We were years ahead of todays organic fertilizer hype. In later years a tractor was used instead of horses.

Over a hundred tomato plants were planted in the garden. Mom protected new plants from the cutworms by using modified quart oil cans from gas stations. She removed both ends of the cans with a can opener and the simple tin cylinder was pressed into the earth around each plant. This also sheltered young plants from the stiff prairie wind. Later in the spring, the cans were reused in other garden areas. When autumn came, they were restrung onto eight-foot loops of bailing wire and draped like huge rusty leis over the nearest wooden fence posts where they remained for the winter.

The ripening tomatoes consumed much of her day and the we all helped with weeding, hoeing and picking. The unsupported tomato vines draped over the ground and had to be lifted to pick hidden fruit. Many bushels of tomatoes were picked two or three times a week. We hauled them in milk pails and wooden apple baskets to the brooder house where they were spread loosely on newspapers on the wooden fl oor. When all the fLoor space was taken they were piled in heaps

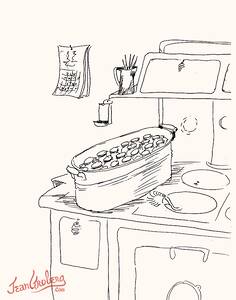

It was now canning time. Jars, hardly sparkling clean after a winter on the cellar shelves, were hauled up from the basement,. Many contained spider webs and mouse droppings and all had to be washed and scalded.

Milk pails filled with scarlet tomatoes that were scalded with boiling water. The skins slipped off easily and the skinned tomatoes were crammed into jars with a little salt and water. Once the glass-lined zinc lids and sealing rubbers were in place, the jars were set on a wooden rack in the big copper wash boiler filled with water that was heating on the kitchen range. The water covered the jars. It took a lot of time and fuel to bring this large container to boiling temperature. Corn cobs and wood were stockpiled and we refilled the corncob basket several times. Each season we helped put up over 200 quarts of tomatoes in this manner.

Imperfect tomatoes were boiled in an open kettle and then hand-cranked through the sieve of a food mill to squeeze out the juice. The pulp was discarded and the juice was bottled and capped in recycled root beer and pectin bottles. The bottles were also heat-processed in the boiler. Pa loved tomato juice.

We had a dozen or more milk cow during the good years before the drought. They were of assorted colors and names. One was called ‘Papa’s Darling’, evidently it was Pa’s favorite cow. We were sent to the pasture to herd in cows that weren’t already waiting in the barnyard. A loud call of, “Here Boss,” or “Come Boss,” usually brought them in. The older kids did the milking.

We had gone up into the hay mow earlier and forked hay through floor openings located directly above the mangers. The cows went directly to the milk stall where they munched on the manger hay while they were tied for milking. The boys perched on the simple T-shaped milk stool, squeezed the bucket between their knees, leaned their head against the cow’s belly and began squirting milk. It made loud, ringing noises as it hit the bottom of the empty milk pail. The barn cats gathered nearby hoping the milkers would shoot them with a well-aimed squirt of milk directly from the udder. A good shot hit the cat in the mouth but any milk landing on the body was okay with kitty. She promptly licked it off and patiently waited for another milky jet. Kids were occasional targets.

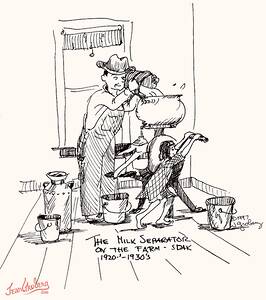

Our milk separator was bolted to the floor of our entrance hallway and was surrounded by five gallon sour cream cans and a few pails. The fresh milk was poured into a five gallon basin at the top of the separator. As the crank was turned, the milk slowly flowed through many spinning discs that separated the cream from the milk. A little bell sounded with each turn of the crank. We liked this job. Skim milk flowed from one spout into a pail sitting on the floor and cream from the second spout flowed into a gallon tin can. A pail of water was run through the separator as a final rinse so the separator was ready for the morning milking.

We fed skim milk to weaned calves. They stuck their heads through the fence and drank the from a small pail. It was difficult to keep control of the bouncing bucket as they butted and jerked. The more adventuresome kids would take the full milk pail into the pen but they had to deal with several hungry animals while trying to deliver the milk to only one. This method required lots of yelling, and kicking and shoving.

Large aluminum kettles of excess milk slowly soured on the warm surface toward the back area of the kitchen range. When a huge curd formed, or ‘clabbered,’ it was drained in a large colander balanced over a milk pail. It was later made into cottage cheese for our table. Leftover cottage cheese was mixed with grain for chick feed.

Soured cream was poured into five or eight-gallon cream cans and stored on the cool cellar steps during the summer. Once filled, the can was hauled by team and wagon, or by a neighbor, to the a Cream Station in town where it was tested for butterfat content. The Cream Station sent it by railroad to a creamery plant where it was made into butter and other dairy products. The farmer usually had two cream cans, each personally identified by cardboard shipping tags or brass plates. When he delivered a full can to the creamery, his previous can was awaiting pickup.

We used cream for cooking and churned some into butter. When the family was large we used a five-gallon wooden barrel-type churn that rotated on a wooden frame as it was cranked. If the little glass peephole on the lid was clouded over, it meant you had to turn the churn a little longer. When you could hear a huge heavy lump tumbling and splashing in the buttermilk, you knew you had butter. We drank and cooked with the buttermilk. The butter was turned into a large shallow wooden bowl where it was patted, flopped and squeezed with a wooden paddle forcing out pockets of buttermilk caught in the dense volume. Butter coloring was used to enhance pale-colored butter. Occasionally butter was packed into a three or four-pound butter crock and artistically patterned with the edge of the wooden paddle. It was taken to the Holdhuson General Store in Houghton and traded for groceries. They sold it to customers. When our family grew smaller we made butter in a hand-cranked, two-gallon glass churn with wooden paddle.

The separator was thoroughly washed and scalded after the morning milking. The thirty sour-smelling discs seemed like a hundred once threaded onto a big rod to be washed. Milk congealed on the tiny rim of each disc and was removed with a knife tip. The hotter the weather the more quickly the milk soured on the discs. Some summers the cows ate pepper grass which imparted such a revolting taste to the butter and milk that Ma had trouble getting rid of the milk products until the pepper grass season ended.

Mother was creative in using the huge volume of tomatoes. After canning some whole or as juice, others were used in relishes and preserves. Some were fried while still green, others were stuffed, sliced raw or used for tomato soup. There was even tomato jam with some orange peeling in it. She should have received an Oscar for salesmanship when she convinced us kids that tomatoes tasted just like strawberries. She was dealing with kids that hadn’t seen many strawberries, and when we were served chopped tomato in a bowl sprinkled with cream and sugar, sure enough, they tasted like strawberries. At least we thought so. Several times. They tasted wonderful until somebody from Minnesota brought us a crate of real strawberries. Tomatoes never tasted like strawberries again.

One year Ma went along the roadside and pulled the young Russian thistles (tumbleweed) when they were only two inches tall and still fern-like and tender. They were steamed and served with vinegar. She called them “Greens”. They were.

Cucumber vines covered a large part of the garden. We picked a bushel every three days at the season’s peak. Ma fixed them fresh from the garden with salt, vinegar and sour cream. A matured cucumber overlooked during picking became large, yellow and inedible. We scooped out the seedy insides and carved them into boats. A wooden match or toothpick for a mast, a scrap of paper for a little sail and we were off to the horse tank to launch our new vessel.

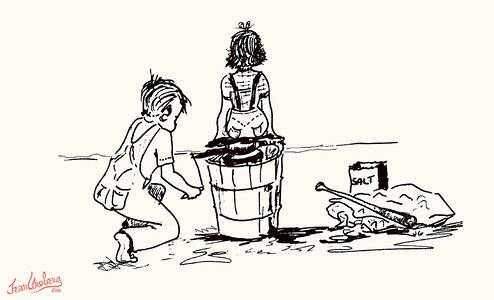

Many three-inch cucumbers were submerged under brine in three-gallon crocks on the pantry floor. This early stage of sweet pickle processing used recipes with names like ‘Fourteen-Day Pickles’, ‘7-Day Pickles’ and ‘Crystal Pickles’. Some recipes required draining and reheating the brine and then pouring it back on the same pickles. The finished pickles were sealed in canning jars.

Occasionally Mom filled a 20-gallon crock with the largest cucumbers and made sun-cured dill pickles. The crock sat in the sun near the clothesline. Wonderful fermenting dill smells drifted through the cracks of the wooden cover. We ate a lot of those pickles while we were playing in the yard, probably before Ma considered them ready.

We picked the little 6 and 8 inch green watermelons if an early frost came before all the melons had matured. Mom pickled them in a salt-vinegar brine in the big crock. After a couple weeks we were slicing pickled green watermelons. They tasted pretty much like a sour dill pickle with a bigger, light- colored interior. One year she grew winter watermelons that were preserved by submerging them under wheat or oats in the grain bins.