Country School

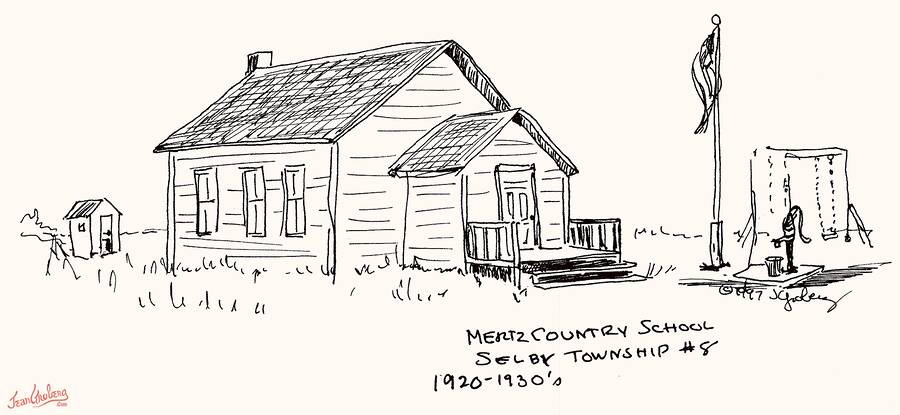

Our country school, ‘Shelby Township School No. 8’, was located on a corner of a section of land about 1 1/4 miles from our home. It was commonly referred to as the ‘Mertz School’ because our large family usually dominated the enrollment which varied from eight to eleven students. On my first day of school in 1930, there were three of my siblings in the same classroom. The water pump and flag pole were a few yards away from the porch of the small, one-room, school building that had a Cloak Room.

The Cloak Room, such a pretentious name. There were no dashing capes, real cloaks or swashbuckling boots hanging about. Our cloak room prevented cold outside air from directly entering the classroom and it was a scramble of jackets, snowsuits, caps and mittens hanging from black wire hooks and sexually segregated at opposite ends of the room. Snowy overshoes dripped into little puddles under the hanging coats.

There was a small barn, boys and girls outside toilets, and some play equipment.

The teacher resided with the closest farm family during the week days. She was usually a young newcomer to the rural community and an object of curiosity and scrutiny to locals. It was probably not a wonderful social life and she didn’t make a lot of money. We had four teachers within six years.

Our favorite teacher, Miss Doris Dolan, was from the small town of Hecla, about ten miles away. She was an inspiring and creative artist in many fields. She taught us to tap dance during recesses and lunch hours, sharing the new steps she had learned during her weekend lesson. I once was her weekend house guest. She lived with her mother and brother. She took me along to her weekly tap dance lesson. She gave sister Verna some nice used clothing.

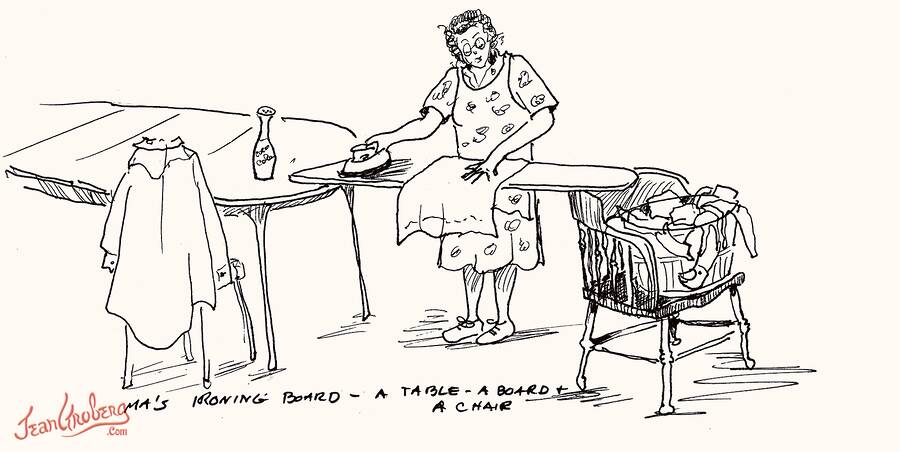

We usually had one school outfit, and many times that was also our ‘at home’ outfit. Many of our clothes were remodeled hand-me-downs from the older girls. Ma was a wizard at the sewing machine. Any new clothing and shoes were ordered from the Montgomery Ward catalog. We determined our shoe size by placing our foot on a measuring scale printed on the catalog page.

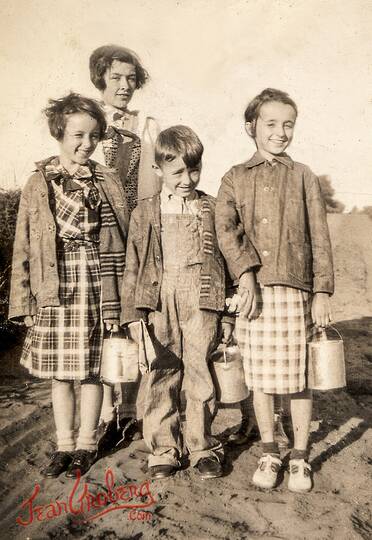

We walked 1-1/4 miles to school. Some students rode horses. Uncle Butch built a horse-drawn, two-wheeled cart that our three cousins frequently drove to school. The horses were tied in the school barn while school was in session. One girl, an only child, was driven to school by car.

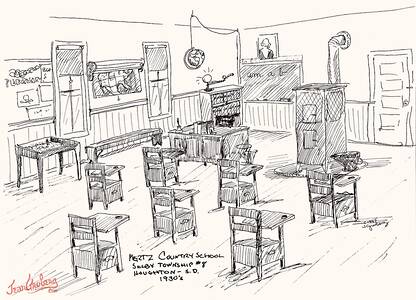

The teacher sat at an oak desk in the front of the classroom. A slate blackboard was mounted on the wall behind. Large brown-toned pictures of Abraham Lincoln and George Washington lent their silent support to our studies from their positions high on the wall .

The teacher’s job was to send us from this schoolhouse, after eight grades, educated in all the South Dakota State requirements listed in the bulky State Course of Study book clamped in the bookends on her desk. A County exam given to all eighth graders was the measurement of the teacher’s and students’ accomplishments toward this lofty goal.

A multi-tiered oak bookcase housed the school library, and it wasn’t much. The protective lifting glass doors prevented field mice from destroying books during the summer months. Other than our textbooks, our school library was composed of a relatively new set of World Book Encyclopedias, two outdated encyclopedia sets and a dozen non-fiction books.

A counterweighted 14” globe was uniquely suspended on a rope laced through two eye bolts on the ceiling. It dangled in the air above the teachers desk. She pulled down the globe when needed, and then easily pushed it up out of the way when finished. The orrey on the bookcase gave a fine cosmic demonstration of earth and moon rotations with the aid of smooth-operating chain pulleys. A set of six or eight maps pulled down like rolled wide window shades from a wooden wall case.

Students in the older classes gathered on two wall benches for class recitation while the younger children assembled on four or five small oak folding chairs.

We sometimes paraded about the room and along the desk rows to the tempo of brisk martial music played on the wind- up phonograph. Sometimes the teacher played the piano while we clattered, clicked, dinged and thumped the clog, cymbals, triangle, castanets and tambourine. We were allowed to play the old black piano before school, at recess and lunch times, but none of us played very well. A peek behind the sheet music panel would find us eye to eye with Mama Mouse and a batch of her naked pink babies all cozy in a nest lined with the felt she had chewed from the interior piano key parts. She must have cherished the summer vacations when the piano sat quietly in the empty building and all the food she desired was available in nearby wheat and hayfields.

The twisted ropes of crepe paper that decorated the bulletin boards and walls was always rerolled and saved for later use. A quart jar of white School Gluey Paste had a wintergreen flavor that one of the girls enjoyed so much she ate it a finger scoop at a time. Another girl considered free sample tubes of Ipana toothpaste a gourmet delight.

We carried our school lunch in Karo syrup pails. In the winter time there might be pint jars of soup in the pails. Early in the morning the teacher placed the opened jars in a flat pan of water on top the coal stove. The soup was warm by lunch time.

Most of the students in the early 1930’s were from economically challenged families. Poor, would be more accurate. Ours was the largest family attending our school. One student, Margaret, was a year younger than I. She was an only child from a family that was not financially distressed. She not only dressed nicely but carried her lunch in a genuine, commercially-manufactured lunch pail with a real thermos bottle. Her wrapped sandwiches were made of white, evenly- sliced bakery bread and were usually spread with purchased Kraft sandwich spread, potted meat or peanut butter. She always had a piece of fruit and maybe a cookie or graham cracker.

I am sure there were times when sandwiches in my lunch bucket were extraordinarily good. However, the bread loaves tended to be dry and hard after a few days in our large pantry storage crock. We frequently filled our sandwiches with canned homemade sandwich spread, a combination of chopped pickles, green tomatoes, peppers, spices and mustard that Ma canned in unending quantity. Many quart jars of this handy sandwich filling stood in rows on a cellar shelf. It was spread in its chartreuse glory on our homemade bread. Once absorbed, it turned the bread transparent on the edges creating a sandwich I felt was to be consumed only in the event of extreme famine. Once assembled, it was dropped, unwrapped, into the lunch pail so the bread dried even more. Wax paper was a luxury we learned to live without.

It was lunchtime at school one day and everybody set their lunch pails on their desks. I pried open the lid of my syrup pail and released the aroma of that acidic sandwich relish. It permeated the humid contents of the lunch pail and assaulted my nostrils. It was one of those sandwiches, still stuck together after bouncing in the bucket during the walk to school. I glanced towards Margaret’s desk as she meticulously unlatched her lunch box and removed a beautifully wrapped sandwich made of lovely, soft commercial bakery bread. She handled her food listlessly. I watched her closely as I took a couple of bites from the soft parts of my sandwich letting the remaining, dry, C-shaped crusts fall into my pail. They made a metallic clank. It was time to approach Margaret.

Our teacher had taught us some tap dancing and I already knew two dance steps. It was time to put this remarkable talent to commercial use. I told Margaret that if she gave me a sandwich I would tap-dance for her. This made two people happy. She was rid of a sandwich she didn’t want and I was the happy recipient. She was highly entertained with a dynamic dance by Miss Twinkle Toes.

Above Photo-Joyce, Verna, Bruce and Jean on way to school 1935

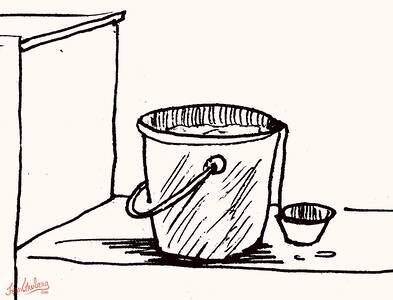

Students took turns pumping the daily drinking water from the well. Water remaining in the bucket from the previous day was sometimes used to prime the pump on cold mornings. The fresh bucket of water was placed on a shelf in the back of the classroom. For several years, everyone ladled and drank from the same long handled dipper, dropping it back into the bucket of remaining water after each use. This unsanitary practice enabled us to share chicken pox, measles, whooping cough and colds with our classmates. In later years the school district furnished a five-gallon crock water fountain with a spigot. The students made personal drinking cups from a folded a piece of paper. Sanitation had arrived at Mertz School.

When it was time for the kids to step out on the school porch to clean the felt blackboard erasers, one could barely make out their figures standing in the cloud of chalk dust created from whacking and clapping the erasers. We breathed a lot of chalk dust.

When it was time to go to school we covered our clothes with heavy snowsuits that Ma had sewn from old woolen coats. A search through the jumbled pile of rubber, buckled overshoes behind the kitchen stove magically produced a pair for each of us to pull over our shoes. Our winter outfit was topped off with stocking caps and mittens that had dried overnight on top the kitchen range warming ovens. We swung open the storm doors and shuffled down the snowy road toward school. The woolen scarves over our mouths and noses became icy from our breath steaming through in little white puffs. Sometimes we walked backwards against a cold wind.

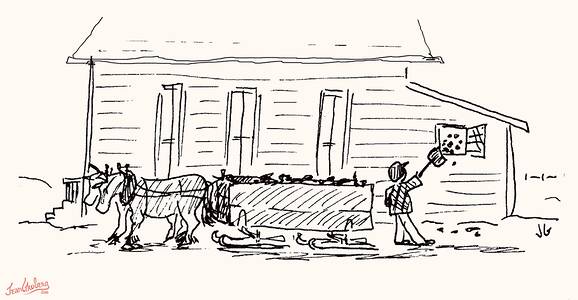

Pa and the older boys made bobsleds from farm wagon boxes equipped with bobsled runners. On bitter cold days Pa or Floyd would hitch horses to the bobsled and drive us to school. We snuggled in the loose straw on the floor of the wagon box, keeping warm under heavy quilts that Ma had sewn from mens wool suiting samples. Sometimes we took one of the heated flat irons from the back of the kitchen stove to warm us during the ride.

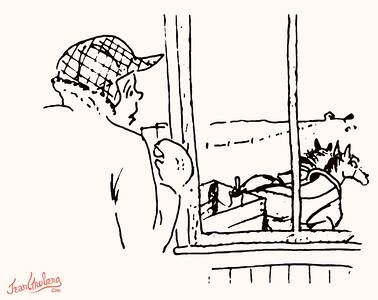

Floyd was about 17 or 18 and not in high school. He sometimes picked us up in the afternoon with the bobsled. It was a treat for us and it gave him an opportunity to get away from the farm. He came into the schoolhouse to warm up and talk to our young teacher before we loaded into the sled for the trip home. One time he became engrossed in their conversation and was startled to see the heads of his team of horses trotting by the school windows heading for home with no passengers and no driver. All of us walked home that afternoon.

If the roads were passable, some farmers drove their children to school in cars that trailed steamy plumes of exhaust, reeking of antifreeze. They peered through a small windshield area they had scraped clear of frost. If a car was parked for a long time, the hood was sometimes covered with a blanket.

Our teacher usually walked the half-mile to school, but sometimes the host farmer gave her a ride on cold mornings. The tall iron stove in the front of the schoolroom burned coal. One of her jobs was to start the fire to warm the room before the students arrived. She didn’t have to go outdoors for a scuttle of coal, for the coal shed was built against the schoolhouse and had a door leading directly into the classroom. She learned to bank the fire at night in order to get a hot fire quickly in the morning. Sometimes the room was still cold when school began and we pushed our desks in a circle around the stove like pioneers circled their covered wagons. We wore our coats at our desks until things warmed up.

Snow began falling early one school day and by midmorning it was pushed by a strong wind. We stayed indoors at recess playing inside games and the piano. By noon the heavy snow was driven in horizontal sweeps limiting visibility. It was the beginning of a grand blizzard. No one came to school in the bobsled to pick us up that afternoon. We pulled on our snow outfits, caps and mittens. Our noses and chins were wrapped with woolen scarves. Only our eyes peered through the crack between the cap and scarf. Verna, a sixth or seventh grader, was the oldest Mertz at school and she bravely assumed the cloak of responsibility.

She tied us three younger siblings together with a length of rope leaving about three feet between and we began the walk home in the blizzard. Visibility was terrible and it was bitter cold. We went directly across the road from the school until we touched the woven wire fence that completely surrounded one square mile section of land. The fence was our guide home. We faced the wind following and touching this fence for one mile north and when the fence turned the corner going west, we did the same. Following the fence about 1/4 miles west until we reached a simple wire field gate. We knew this gate was directly across the road from our farm driveway. We crossed the road into our farmyard and could see the house and smoke coming out of the chimneys. Our parents were very happy to hear us stomping snow off our overshoes in the hallway. Ma had been standing at the window mentally pulling us home. Verna had done the rest.

We played Fox and Geese tag games on trampled paths in fresh snow and dueled with the long icicles that clung to the eaves of the barn and toilets during spring thaws.

We tumbled snow into balls so huge they required several children to turn them over. Dry snows pushed by heavy winds made dense, hard-packed snowbanks. A couple times we took Pa’s saw to school. During the lunch hour we sawed the snow banks into blocks and built circular igloo forts large enough to hold everyone in school. One year, we built a snow-block spiral maze taller than our heads.

In 1930, when Charles Lindbergh was a popular hero, an enterprising manufacturer marketed Lindbergh-style children’s aviator helmets made of black and brown imitation leather. Of course, they came with important- looking goggles. Each of us Mertz kids had a Lindbergh helmet that projected us into the giddy wave of kid fashion. The goggles were the perfect shield from windy sandstorms. We liked our heroic appearance as much as the protection. Many windy days during the depression we walked to school with handkerchiefs tied around our mouths and noses to keep from breathing the blowing grit.

Like todays children, we played games at recess. Sometimes the teacher joined in. When a skunk took up residency in the boys toilet, the girls teased the boys who were forced to do the unthinkable: they had to use the girls’ toilet. In the spring we picked wild pasque flowers from the native grass pasture across the road. Spring was the time to unfasten the supporters holding up our long stockings and roll them to the ankle. This revealed our long underwear which we immediately rolled into a bulky roll to a point above the dress hemline. Cool. Chic!

One rainy afternoon when I was in the third grade, the whole classroom was busy with school work. Thunder, lightning and drenching downpour vied for our attention and lightning won the contest. Big time. The rumble of a distant rolling wave of thunder came nearer and louder and suddenly culminated in a tremendous ear-splitting explosive thunderclap. At the same instant, lightning struck the schoolhouse chimney, traveled down the metal stovepipe with a blasting, crackling ‘Ker Whoom -Bang’! A ball of fire, six to eight feet in diameter, exploded near the ceiling over the stove. The thunder clap and the lightning strike combined made a deafening sound. It was terrifying. We learned what ‘Fast as a bolt of lightning’ meant on that day. Within seconds the teacher had a roomful of crying kids. Those who weren’t crying were scared quiet. There was no telephone at school so the parents, not knowing what had happened, followed their usual routine. The kids got on their horses, walked home or waited to be picked up at the usual time.

The Brown County Schools sponsored a Declamatory Competition every spring. Schools students spent hours memorizing and reciting poems and readings with great passion and even greater facial expressions. This was high drama, country style. When regular class work was done, two students at a time were permitted to go to the Cloak Room, close the door, and quietly recite selected poems to one another while their schoolmates remained at their desks. To be on our own, away from the teacher was a special privilege. We kept any silliness and giggling muffled with a hand over the mouth.

The winning students from our school competition went forty miles away to the Aberdeen Civic Center for the county- wide contest. Kids, dressed in their very best, stepped before a microphone for the very first time and in loud, excited voices recited the writings of poets such as Edgar A. Guest and Longfellow. “Be sure those people in the back row can hear you,” was the last command of their teacher before they stepped onstage. Some of the poems were real clinkers offering many opportunities for broad hand gestures and lots of rolling of the eyes. Poems that began with:

“Who stuffed that white owl?

No one spoke in the shop,

The barber was busy and could not stop---”

or

“My Pa held me up to the Moo Cow Moo,

so close I could almost touch,

I fed him a couple a times or two,

I wasn’t a ‘fraidy cat, much.”

Their schoolmates were present and proud.

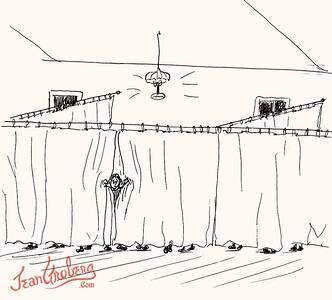

School programs were held in the evening with most farm parents attending. This was an opportunity to recite poems memorized for the declamatory contest. Bed sheets were brought from homes (not ours, they were in use) and converted to stage curtains when they were safety pinned to taut wires outlining the stage. The safety pins glided smoothly along the wires so curtains could easily be pulled aside for the performance. The audience sat on the recitation benches, desks and wooden folding chairs. Additional bench seating was created when planks from the school barn were placed to span the space between two desk seats. One evening there was a school program. Pa wasn’t home and so Ma walked the l-l/4 miles down this dark country road with four or five of us kids to get us to school so we could perform in the program. It was dark, and it was scary. No lights were visible from distant farms and there were certainly NO automobile lights. It was nice to get to the school building which was lighted by lanterns and lamps people had brought from their homes.

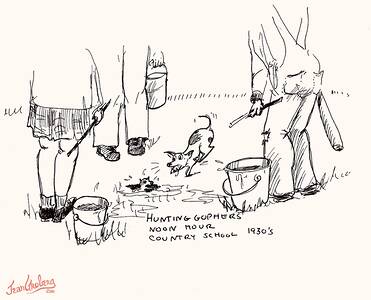

The three-cent bounty paid for every gopher tail redeemed at our township board was a sure way to put money in our pockets. Any hapless gopher foolish enough to be running in Uncle Butch’s hay pasture across from the school during recess or noon hour was in serious trouble--and he knew it. When he saw us, he took off running, his little tail straight in the air, disappearing into the first available hole. He was dealing with skilled gopher hunters. Hot on his four little heels ran our whole student body, eight or nine shrieking, yelling kids waving sticks and baseball bats in the air. Our water-filled lunch buckets sloshed and spilled as we ran. We didn’t really want to hurt the gopher, all we wanted was his tail, and he was not about to hand it over without a little mayhem. We poured the water down the hole and the drenched gopher emerged, unable to withstand the deluge. We chased him again until we caught him, killed him and took his tail. The tail went to the lucky person who first saw the gopher. It would later be redeemed to the Township Board for three or five cents per tail, depending on the species.

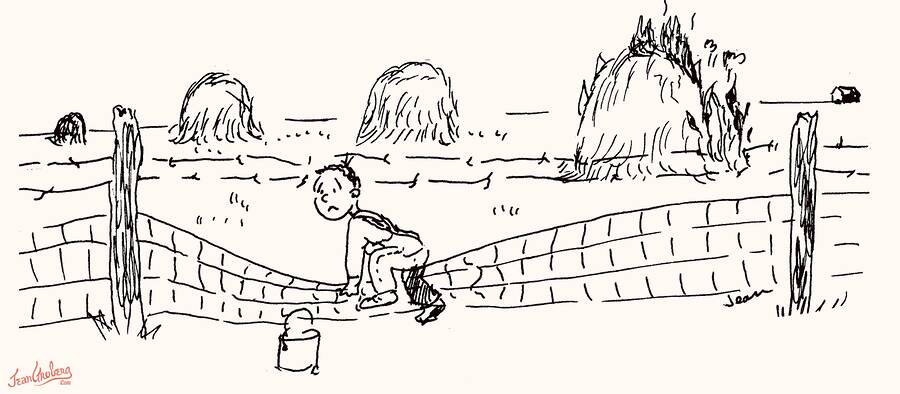

One morning on our way to school, Verna, Joyce, Bruce and I took a shortcut through Uncle Butch’s pasture right across the road from the school yard. The hay had been cut, dried and stacked into several huge ten-feet tall haystacks. They were destined for animal feed during the winter. We walked around the haystacks and crossed directly to the fence line. We then crawled under the barbed wire and crossed the road into the school yard. Bruce, our first-grade little brother, apparently had fallen behind when we crossed the pasture and he suddenly scurried from behind a haystack to join us.

We had barely stepped inside the schoolhouse when someone noticed a fire in the hayfield, precisely in the area where Bruce had briefly been out of our sight. Flames licked up the back side of a haystack and it was completely destroyed. Local men, when they saw the smoke in the distance, came and beat the flames with wet burlap bags to prevent the fire from spreading. Bruce had taken this opportunity to practice igniting wooden kitchen matches farmer style: by scratching them on the suspender button of bib overalls as he had seen a neighboring farmer do it many times. Pa paid Uncle Butch $75 for the lost haystack.

You knew that it was serious business when the County Nurse drove 40 miles on dirt country roads in one of the those 1930’s cars just to nail this ominous sign on your house. “QUARANTINED”. It warned visitors there was a communicable disease at your home. It was nailed on our house once, probably when we had whooping cough. It didn’t affect the activities of us kids but probably limited activities of the adults and older siblings in the house.

The County Nurse made called at our school once or twice a year. She would weigh and measure us, look at our throats, administer the small pox vaccination and a scratch tuberculosis test. This was the only time we were ever weighed. She weighed me when I was nine years old. I weighed 44 pounds. I proudly wrote this to our oldest sister, Dorothy, who, saved my letter. I was skinny, and was always being asked “Why doesn’t your mother feed you?”

Our country school enrollment dropped to a less than six when I was in the sixth grade. We were down to the last three Mertz kids and two of our cousins. The district closed the school and sent us four miles away to school in the small town of Houghton, population 107. Town School. Hot dog. We were headed for big stuff.

We attended school in Houghton when our country school closed. The town school building had three classrooms: one for the first through fourth grades and another the fifth through eighth grades. The Freshman and Sophomore class were in the third room. Three teachers were employed to teach all ten grades.

The township paid Uncle Butch to transport us and his three daughters to the town school. I was a seventh grader and apprehensive about a huge schoolroom with many children and a male teacher, Mr. Smith. We had heard all sorts of stories about strict male teachers. It turned out that Mr. Smith was a very creative teacher. He did lose patience with a couple of the less-motivated students. There were about fifteen to twenty students in the four grades in his classroom. A majority were town kids: offspring of the depot agent, the grocery store owner, the Rural Free Delivery postman, a church leader, the gas station operator, pool hall operators, assorted farmers with town residences and farm kids like us.

Mr. Smith, a poet himself, taught us to keep journals. I interpreted that to mean that I was to write a poem every day, and I did, composing poems about the weather, the sky and my brothers and sisters. Any subject became a target. I was a conscientious, terrible poet, spinning short rhyming sentences with great abandon. All were really quite awful but Mr. Smith heaped on the praise and I read them to the class and hurried to write some more. I liked that attention.

All ten grades were released at recess time onto the grassy play field across the street. Its prairie grass was mowed with a hay mower. The Giant Stride, a tall metal pole dangling with multiple clanging chains, swings and teeter-totters were placed close to the building. It was nice to have so many kids to play with that I was not related to. Boys and girls of all ages played the same games together. When I was an eighth grader, I bumped heads with the depot agent’s son while playing football and broke my nose. This caused my first trip to a Doctor, forty miles away to Aberdeen. He pinched my nose to straighten the bones, however, he either did a poor job or I sabotaged his fine work with additional bumps over the years as my nose definitely points to the right.

My Sister Dorothy and her husband Rudy lived in Columbia occasionally I would Visit for a few days. An additional attraction when staying with Dorothy and Rudy in 1936 was to enjoy the rituals of Saturday night in downtown Columbia, a town of about three-hundred people. Farmers would hurry to milk cows and do their chores so they could drive their wives and children into town early in the evening. The early arrivals left their weekly five-gallon can of cream at the creamery and parked their car in one of the highly-prized parking spots in front of the stores. By the time their groceries were purchased, it would be twilight. The wives returned to their parked cars and sat quietly nursing their babies in the front seat. Any tired toddlers in the back seat were mollified by an older child delivering an ice cream cone or a corn sucker lollipop the shape of an ear of corn.

From their seat in the car, the women would watch, wave and call out to other farm families going in and out of the grocery store and the drug store. The farm wives kept a lookout for their friends sitting in the cars. Once the groceries were purchased, the car hopping would begin. Usually one woman would stick her head in the open car window and talk for a while to her friend. When it was decided they had lots to discuss and a big bundle of time before their men returned from haircuts or the Pool Hall, the visitor would be invited to sit in the car. It was like a small living room on wheels. Excited older farm children walked up and down the sidewalk trying to make their ice cream or popsicle last as long as possible.

The fathers headed to the Pool Hall to lean on the long bar, enjoy a beer. Some took a couple spats at the brass spittoons. There were a few tables for card players and a pool table toward the back of the room. The little one-man barber shop next door had a busy Saturday night. There was always a man with a ruddy tan face and white forehead in the barber’s chair. A handful of farmers, awaiting their turn, sat in a row of straight chairs lined against the wall. A few would lean against the window sill of the square front window, all engaged in watching haircuts. There was a great exchange of crop information, the latest edicts of the Department of Agriculture, soil erosion, calving, and all the other details that go with farm crops and animals. Hopefully a neighbor may already have a solution to a farmer’s current problem.

The teenagers provided a restless backdrop to this folksy downtown Saturday night scene. Those with cars drove the length of Main Street, all five or six blocks. The gravel crunched as they hung slow U-turns around the light standard in front of the old hotel. They repeated their slow Main Street cruise again and again to gain maximum visibility, and also to catch sight of any friends on the sidewalk. See and be seen, that was the game. A contingent of teen-aged girls sauntered up and down the sidewalk, their gaze ever alert for the boys and their cars. Up and down they strolled, and up and down the boys drove in this ritual ballet. Occasionally a car eased to a crunchy stop in the middle of street and the girls would walk over, lean into the open window and talk to the driver and his friends. Sometimes one or more accepted an invitation to get into the car.

I usually joined the girls of grade school age, spending the evening walking to the end of the sidewalk in front of the stores talking in exaggerated, excited whispers. It all seemed so sophisticated, so ‘up town’. There wasn’t this kind of excitement on the farm. Boys our age lurked in the shadows. One could hear the stones fly as their bicycles spun dusty arcs in the gravel. We would squeal, and run. Such was the excitement in 1936.

After a couple hours of this stimulation, the chorus of bawling tired kids sung in unison from the parked automobiles. Parents would round up their tired broods and stuff them in the back seat among the groceries. The wails of weary children drifted from the car windows as they were driven out of town toward home. The Saturday night social time was at an end.

Dorothy got married at the farm home of her future in- laws and our whole family attended. Chairs were set up in the living room, and Joyce, about 8, managed to trip and spill one of the vases of flowers placed at the end of each row of chairs. She was mortified.

When Dorothy and Rudy had their first son, Joyce and I took turns being a ‘mother’s helper’ at their home in Columbia, just like we had done at brother Donald’s house when he and his wife had their first baby. Dorothy, in her early twenties, knew her younger sisters well and made an effort to get us involved in cooking projects we would enjoy. It was fun being there. As a young bride and mother in her first home, she had established an ambitious routine. She was intent on being the best little wife possible. She had a specific day for washing, mopping, and dusting. It was difficult for an eleven-year-old to understand the need to dust on Wednesday if there was no visible dust, but dust I did. It was not as satisfying as dusting back at home where we had visible dust, fine-grade silt that settled on the rungs of chairs and window sills. When you dusted at our house you were making a difference.

A community picnic celebrated the end of the school year. It was a spring social event. Students and parents of all ten grades participated and the whole town turned out. The Catholics, Wesleyan Methodists, Congregationalists and Lutherans all mingled amicably. Some of the farm fathers, easily recognized by their white foreheads and ruddy skins, showed up for the picnic after a day in the fields. The ladies wore their nicest print house dresses and the men their better pants, or their newest, crispest denim overalls.

A few oak folding chairs from the school building were placed on the edge of the grassy field near the tables that the local women had burdened with food. There was Jello, potato salad, green olives, home-made pickles, deviled eggs, sandwiches plus wieners and marshmallows to roast. This was the time for the women to show off their multiple layered cakes, all fluffy with shredded coconut caught in the sticky icings. Several hand-cranked ice cream freezers, each holding two gallons of ice cream were carefully packed with ice and salt and covered with burlap bags awaiting dessert time.

Farmers and men from town played ball with the students. There were organized foot races, broad jumps, potato sack races and tug-of-war, games usually played only at picnics. Young children played on the swings and teeter-totter. The older kids stole chunks of ice from the tops of the ice cream freezers which they dropped down the back of their friends shirts. This was followed by long intricate chases around the food tables, much to the consternation of the women who tried directing the running away from the laden tables. Girls encouraged the boys to chase them by merely taking the boys cap and running with it. Some women busied themselves hovering over the tables swishing flies with their best embroidered dishtowel. Others were caring for the little ones or sitting in a car nursing their babies. Adults caught up on community gossip and exchanged crop problems as they lounged on Beacon blankets or old bedspreads that had been spread on the grass.

Only darkness brought a halt to all this fun. Car lights were focused toward the playing field and lighted the picnic area to aid in the cleanup. Trunk doors yawned as ice cream freezers and picnic paraphernalia were stored for the ride home. You could hear the tearful cries of tired children, reluctant to end such a fine time, and yet too tired to continue. The farmers and their kids headed home to milk the cows. The town kids were scampering across the play field in the early darkness in one more game of tag to extend this wonderful day. A few freshmen and sophomores talked quietly by the side of the school building, planning their next encounter.

Going to Houghton High School as a Freshman and Sophomore was like stepping backward. The school building was very familiar for it was a little one-room country school that had just been moved into town. It wasn’t even as big as our old Mertz country school. This was supposed to be the new, and not-so-improved two-year Houghton High School. There were between twelve to fifteen students in the two combined classes. We were taught by a well-dressed, middle- aged teacher, Mrs. Powell, who did a fine job of encouraging our interests in Geology, Biology and Mathematics.

Four rows with four timeworn desks in each row, trickled down the center of the small 16’ x 20’ classroom. Some desks had fold-up bench seats, decorative cast iron legs, holes for inkwells and lift-tops well-carved with initials. Aged chewing gum deposits clung to the underside of the desktop like barnacles on a boat hull. The stove was in the front of the room. It was like our old country grade school with bigger kids. Even our recesses were held at the same time as the grade school children. High school and grade school students mixed freely. Boys and girls played softball or football together.

We attended class without leaving our desks. The freshmen Algebra students overheard the sophomore Geometry class, everyone listened to everybody’s classes. There were no organized athletic teams nor were there academic electives. We were fortunate to have a dedicated, teacher whose summer travels enriched our curriculum. She returned in the fall with new seashells, pressed flowers and mounted insects and butterflies. She brought rock samples and petrified wood and from travels on the Columbia River. She occasionally read to us. We worked from our textbooks and a set of encyclopedias. There was no library. In 1938 the two classes took a field trip to Aberdeen, forty miles away, and that was a big event. We visited the Coca Cola bottling plant and the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad roundhouse and topped off the trip with a picnic in Wylie Park.

There were eight or nine buildings on the Main Street of Houghton. One was a dance hall built in the 1930’s by Mr. Valentine, the gas station operator. The Friday night dances drew young people from surrounding towns. During the Freshman and Sophomore years, I stayed in town after school on dance nights to work as a waitress at the Hotel across the street from the dance hall. I attended the dance and then hurried back to the Hotel at supper time’ to serve hamburgers, French fries and coffee to the dance crowd. This was a happy night in town.

I was fifteen in the early summer of 1940 and brother Floyd, who was working as a hired man at a farm in Minnesota, came home on a visit. I rode back to Minnesota with him so I could find housework there. I spent the summer living with and working for a Minnesota family who had a girl near my age. We released the windmill lever to pump water for household use and hauled the filled water buckets to the house in a child’s red wagon. I learned the difference between Minnesota well water and the ever flowing artesian water of South Dakota. I learned it was wise to shampoo hair in the softer rain water available from an iron cistern pump on the kitchen counter. Most homes with outside toilets had a chamber pot available for indoor nighttime use. Every day we had to go empty ‘Gracie’, the chamber pot.

One weekend while I was in Minnesota, my brother Floyd, about 22 years old, was having a party at the farm where he worked. The owners were gone, their daughters, Pat and Ethel B., were home. I was invited to come and to stay overnight as Pat was my age.

Floyd had been shopping for a new car and had a used sedan on trial from an auto dealer. It was twilight and the party had not begun. I went out of the house and sat in the driver seat of Floyd’s loaner car. The keys were dangling from the switch, I turned them and pressed the starter and the car started. The sound of the motor brought Floyd to the kitchen door to see what was happening.

I had never driven a car, but it seemed I should give him a little show. I knew how gear shifts worked and I knew how a car was supposed to sound when you drove it as I had heard Floyd start a car many times. After the engine started he always hit the gas pedal several times. VROOOMM, VROOOOOOM, VROOOMMM, the motor reverberated with loud sustained bursts and then he would ram the car into gear. Since he was already standing at the door watching, I hit the gas pedal many times and got many, many ‘VROOOOM’s’, and then I jammed the gear shift into reverse, just like Floyd always did.

That sedan cut a 90 degree arc across the yard, going backwards so fast that it was but a mere second before I rammed into the hog yard gate and the back wheels were in the muck. Floyd stood on the steps by the back door of the house overcome with laughter. Tears rolled down his cheeks as he came across the yard followed by Pat and Ethel B. I didn’t think there was anything funny and was scared to death. There was a lump in my throat the size of an apple and I could scarcely hold back the tears. The car barely got a scratch, Floyd fixed the gate and the party began on schedule. Floyd decided not to buy that car. I had no desire to solo drive for several years.

Room and Board with Sister Dorothy

In September 1941 it was time to move away from home to finish my Junior and Senior High School years in Columbia. Commuting the thirteen miles distance was out of the question for we had no car. Columbia High School occupied the second floor of a two- story school building. The lower grades used the first level. There were outside toilets.

A teacher monitored a study hall confining the whole High School student body of fifty to sixty students into one room. We left study hall to attend classes in one of the three separate classrooms. There was a typing room with a dozen manual typewriters.

My sister Dorothy and her husband Rudy lived on the edge of Columbia within easy walking distance to school. I lived with them during the beginning of the school year. I helped Dorothy with housework and the children. I baby sat when they went to the ‘Married Folks Dance’ or other outings. I kept Rudy’s cigarette box full with cigarettes that I rolled on his cigarette rolling machine using Model Smoking Tobacco.

They milked two or three cows and had their cream separator in a separate building. A fifty-gallon steel barrel of water was solar heated on top of that building and the warmed shower-bath water was piped into the Separator room below. A shower drain was made from an iron wheel rim filled with cement and the water drained onto the ground under the building.

Before the year was over Dorothy and Rudy moved to their own farm outside of town and I had to look for another place to live. World War II had begun.

We declared war when Pearl Harbor was attacked by Japan in December, 1941. I was in my third year of High School.

The following summer, I worked at the cafe in Columbia as a waitress for $5.00 a week. A step up in the world. Three of us girls, all about 16 or 17, were the waitresses, dishwashers, cleaners and assistants to the cook.

The food was home made and good. Each day we recited the usual menu of hot roast beef or hot pork sandwiches to the regular customers who perched on the counter stools. These sandwiches required that two slices of white bread be smothered with slices of hot meat, a scoop of mashed potatoes was plopped on the meat and the whole affair was slathered with a rich gravy. The hot sandwich was ready to be served. The cook’s secret for nice brown gravy was using caramel colored syrup made from burned sugar.

It had been but seven months since Pearl Harbor was bombed and our Government started defensive activities on many fronts. Already, there was a glider pilot school a few miles south of Columbia. Motor-less manned gliders were towed into the sky, the tow rope was disconnected and the young men learned how to handle this quiet craft in the air currents and to land it safely. This became one of the ways to move men across enemy lines.

Some pilots and mechanics were regular customers at the cafe. The mechanics came in after work with their empty lunch bucket. While they ate their evening meal, the cook packed their lunch pail with sandwiches for the following day.

We referred to one mechanic as ‘Mr. Bunch Of Stuff’. When his battered car pulled up out front one of the waitresses would call out, “Here comes Bunch Of Stuff.” He was a tall, lanky fellow with uncombed, straight, oily hair. His striped overalls were covered with the same grease and oil that traced the creases in his knuckles. No doubt he was a whiz with a wrench in his hand, but he was acutely uncomfortable in the civilized cafe setting. He was probably a farm kid on his first big paying job, and had never before ordered food in a cafe. He had no desire to hear us recite the menu and would interrupt our recitation by saying, “Just give me a bunch of stuff.” This way he did not have to suffer the embarrassment of asking us, “Just what is a hot beef sandwich?” When asked what he wanted in his lunch pail for the following day, he gave the same answer, “Oh, just put in a bunch of stuff.” This was not a fellow who liked to make decisions. He didn’t vary, nor did our menu. The cook loved him.

During my Senior year of high school I worked for my room and board for Mrs. Evans, a lady in her mid-80’s. She was a short woman, with straight gray hair, bluntly cut at earlobe level. Her hearing was keen, but her blue eyes were clouded with a milky cataract glaze. She wore floral printed house dresses that flirted with her puffy ankles. She quietly shuffled about the house wearing blue felt house slippers and was always closely followed by Fluffy, her aged, vision- impaired poodle. Fluffy was no longer fluffy, in fact he was two- thirds naked. Dark gray spots of varying sizes randomly spattered his exposed pink hide and his once-elegant tail looked more like a ruddy rat’s tail with a few clusters of white hair sparking off the tip. Fluffy had an acute case of mange.

My duties were to buy the groceries, clean house, cook our meals on the wood burning kitchen range, keep the living room stove fire burning, change bedding and wash clothes. I hauled in the wood or coal for the fires, and emptied Mrs. Evans’ chamber pot in the outside toilet. It was hoped that I would learn to administer her daily insulin shot. Mrs. Rathert, a nearby neighbor had performed this thoughtful service for Mrs. Evans for years and gave me a demonstration on how to give inject insulin into Mrs. Evans’ billowing underarm flab. She worked quickly, thrusting the needle into the flaccid sack of flesh, quickly pushing the plunger and withdrawing the syringe before I could count to three. Bingo! Instantly a small bubble, much like bubble gum, puffed up the flabby tissue. It was nauseating. I was seventeen, and wanted no part of this activity. The other work was no problem. Mrs. Rathert kindly continued to administer the daily insulin shot.

A wide, draped archway separated the living room from Mrs. Evans’ bedroom. Her four-room cottage had a small, unfinished attic with a roof so low that one stood erect only in the very center. This tent-shaped cavity was my bedroom. Bare 6” planks covered the floor. A previous occupant had randomly pounded a handful of large nails into the exposed 2 x 4 roof supports providing a great place to hang clothes, with or without hangers. This same creative genius tied a cord to the end of the iron bed and connected it to the chain dangling from the naked light bulb that hung from a rafter. Once in bed, a quick yank on that handy cord and the light was off. Heat drifted up the stairway from the living room and made the attic cozy and comfortable. I liked it.

A high school with a student body of sixty students is a friendly school. There were many evening practices for basketball games, singing, and high school plays. Students with a nickel sometimes went down to Main Street and had a Coca Cola at the drug store or cafe. Sometimes we visited our classmate who lived with her mother and sister in a small apartment above the cafe. They were the local telephone operators for that part of the county. The switchboard which was necessary for the job was placed in the corner of their living room. We would lower our voices if the switchboard buzzed. One of the women would put on the earphones and say, “Number Please.” She would then make the requested connection. She would sometimes tell a long distance operator that a certain party didn’t answer because they were probably at the basketball game. Long distance operators didn’t appreciate information being given to a caller before a paid connection was established. Many nights we stayed there late to hear the mystery-thriller radio program The Shadow or The Squeaking Door. Later on we would walk the three blocks home in the dark, scared to death. I was home by 9:30-10:30 p.m. on week nights. Basketball games or dances on weekends usually meant staying out later.

No matter if I returned home early or late, no matter if I was as quiet as a mouse, I could be sure that Mrs. Evans’ little dog would bark hysterically to announce my homecoming. The wide, draped archway leading to her small bedroom was three feet from the front door and Fluffy, the dog, slept by her bed. As soon as I opened the front door the scroungy little mutt would scramble from her bedside, his claws skidding on the bedroom linoleum as he bounded through the draperies, yapping fiercely. This commotion was followed by her wavering voice calling, “Is that you Jean?” I answered affirmatively and quickly went up to bed. This was not the end of the episode. My arrival and her fiercely protective dog had disturbed the old lady’s sleep. She would stay awake and listen for the next chime of the dining room clock and count the number of gongs announcing the hour.

She filed this information in her memory bank, and the following morning she would say in a kindly, but scolding way, “My, Jean, it was awful late when you came in last night.” I didn’t think 10:00 or 11:00 was very late at all.

Mrs. Evans knew my activities. It was hard to get into trouble in a small town of three or four hundred people. Basketball games and major school activities were booked on Friday nights. Saturday nights we would sometimes go to a community dance in Houghton or Frederick, 14 to 20 miles distant. I liked to dance. Jitterbug (swing) and fox trot were the popular dances in 1942.

Dances in these towns, lasted until 1:00 a.m. and it would be 1:30 or 2:00 a.m. before I got home. I hated being barked into the house by that dog and being scolded about the late hour when I had only danced and behaved myself. She probably felt responsible for me like I felt responsible for her.

One Saturday night I had a date for a dance in the town of Frederick. I knew the dance lasted until 1:00 a.m. and by the time we drove home it would be 2:00 a.m. I came up with a trouble-free idea that would allow a late return without the hassle. Nothing could be done about Fluffy’s barking, so I confronted the tell-tale clock by turning the time back several times. I began this operation early on Saturday morning. When the clock read 9:25 and was about to sound the half-hour gong, I quickly moved the minute hand backwards to 9:05, slowing down the clock 20 minutes per hour. The clock was allowed to function properly for the balance of that hour. A couple hours later the same adjustment was made. The clock manipulations were spaced throughout the day and hardly noticeable. The early winter darkness worked to my advantage and made it difficult to judge the time. Mrs. Evans rarely listened to the radio and her vision did not permit reading. I felt secure. By evening the clock was two hours slow.

Before departing for the dance, I banked the fire in the living room stove. When I left, she was sitting in her rocker with her slippered feet caressing the warm metal stove legs, absorbing the comforting heat. The scissors were in her lap and it looked like she was going to spend the evening seeking the stray long gray hairs that sprouted on her chin and cheeks. Snip, snip. I had heard her clip those wayward whiskers many evenings. I said goodbye, and went with my date to the dance.

Like Cinderella at the ball, the evening flew by. Too soon, the band was playing Home Sweet Home, followed quickly by Good Night Ladies. It was their signal to the crowd that it was 1:00 a.m., the dance was over and it was time to drive home. It was almost 2:00 a.m. when I unlocked the front door, but the maladjusted clock had not yet chimed the midnight hour. The scheme had worked! Mrs. Evans’ bedroom draperies jerked and bounced as the dog bounded through as usual, broadcasting my arrival with his frantic barking. I quietly eased the door shut as Mrs. Evans called out, “Is that you, Jean?” I answered, “Yes.” Then, in a quavering voice she added, “My, this has been the longest evening!”

Early the next morning the dining room clock had to be reset before she arose. She was snoring loudly in her bedroom, catching up on the sleep she had missed the previous night so she didn’t hear the clock’s multiple gongs as I advanced the hands through two hours to correct the time. I never did that again.

Mrs. Evans’ must have had a lot of confidence in me as a seventeen-year old cook. She decided to invite her son and his family, who lived on a nearby farm for Thanksgiving dinner. She didn’t get about very well so the cooking was up to me.

In those days the Thanksgiving turkey arrived in the kitchen dead and plucked of most of its feathers. It still had feet, head and intestines and a few pin feathers that had to be removed with a pliers. I had helped Ma do that several times. I had eviscerated chickens before, but never a turkey. Mrs. Evans’ old, dull butcher knife didn’t make this revolting process any easier. Lopping off the grayish-purple feet and knobby red head was the easy part. Mrs. Evans was not too helpful as she couldn’t see well enough to do anything. She hovered over me and the wood kitchen range until I got the turkey in the oven complete with a stuffing. The table was set and the potatoes peeled.

When her family arrived for dinner, her son prepared to carve the turkey. I set a platter for the meat beside him. I glanced over his shoulder and discovered, to my dismay, that my amateur gutting job had left the turkey’s anus in place. Her son made no comment as he removed the meat and dressing, working around the surprising embellishment. Such a gentleman. It was acutely embarrassing.

It was a dark Sunday evening before Christmas during my Senior year in High School. I was embroidering some pillowcases in the living room and Mrs. Evans sat in her rocker, caressing the warm stove legs with her slippered feet and pulling out the 5/8” white whiskers on her chin. Each one took several yanks. Some nights she clipped them. Snip, snip those scissors would chatter. Fluffy the dog lay at her feet trying to warm his pink hairless skin and occasionally he gave a little shudder as a chilly draft enveloped his nakedness. A group of Christmas carolers from a local church appeared on the porch and Mrs. Evans had me invite them in to finish their song out of the bitter cold. After their departure, she mentioned of being so ashamed that I had been caught sitting there sewing on the Sabbath, a restriction I had never before encountered.

Mrs. Evans became ill shortly after Christmas and I stayed home from school and took care of her for two days. Even after receiving my fine, inexperienced, nursing care, she still ended up in the hospital. Once released from the hospital, she went to live with her son’s family. I moved in with a family that lived next door where Darlys, a young woman, two years older than I, was caring for her terminally ill Mother and fifth-grade twin siblings. I was a helper, at least I hope I was, because Darlys had a lot of responsibility for a 19 year- old girl. I was not there very long, but it gave me a place to be until I could find another place to live. When I graduated from high school, Darlys loaned me her formal to wear at my graduation and prom.

Doctor Martin in Columbia was a large friendly man with a fat stomach. He did not maintain regular office hours. Unofficially, his door was always open. The big round kitchen table was his dining table, office and pharmacy. It was stacked with a tumbled array of medical literature, medicine samples, opened medicines, sugar, table condiments and a large jar of Hemo, an Ovaltine-type product popular at that time.

When my bad sore throats turned into tonsillitis I went to Dr. Martin for help. He dispensed immediate treatment from the mounds of samples at the center of his breakfast table. My throat was then immediately sprayed with Merthiolate delivered from the long- nozzled atomizer on his window sill. There were no antibiotics or penicillin available then. He and his short, plump wife were a cheerful couple. During one of my visits they told me of the roll of linoleum they had purchased for their living room. Age and physical condition had stolen their agility. They needed help to lay it and hired me for this job, probably knowing I needed the money. Having never seen a new roll of linoleum, nor the installation process, one could truthfully say that I was perfect for the job and could approach it with an unfettered mind. To a seventeen-year-old, everything is possible, even simple. There is the floor. Here is the linoleum. Lay Number Two on top of Number One.

We couldn’t move the heavily-laden china closet, the hefty secretary desk with the fold-down shelf and some other heavy furniture along the walls. No problem. With their encouragement, I knifed away the linoleum around the base of the cabinets, and probably not too well. They seemed to know the limitations of their hired girl and the hired girl was aware of theirs. They were not requiring a precision job which is exactly what they didn’t get. They made me feel I was doing everything just beautifully and seemed downright grateful, I liked this colorful pair.

Once more, I was looking for a place to stay while attending school. Donna, a Junior in High School asked me to live at their house. It was surprising that this family found room for me. Their home had been destroyed by fire and they lived in some rooms on the second floor of a nearby home. The Mother worked in a downtown grocery store and the Father was a quiet man who operated a road grader on the graveled county roads.

There were three bedrooms and a kitchen. The parents and the seventh grade girl each had a bedroom. The third bedroom was shared by Doug, age 17, Donna and me. Donna and I slept in the double bed, and Doug used the single bed. He had been crippled from infantile paralysis when young and walked on crutches. His legs were supported by hip- high metal braces with leather straps laced to the thighs and calves of his undeveloped legs. The braces made a clanking noise when he shoved them under his bed at night. When the braces were sent away for adjustment, he had to crawl around on the floor for a couple of weeks until they were returned. He developed muscular shoulders, drove a car and played the guitar. His friendly disposition and good looks made him popular at school.

There was not a lot for me to do to justify my presence in this small apartment. They were nice to include me. When a house became available a few blocks away, the whole family moved. Donna and I no longer had to share the bedroom with Doug. Her mother sewed things for me as well as her own daughter. These people were so kind. I was fortunate.

When I got the mumps I had no way to get home to the farm to recover, and no way to let my folks know I was sick, so I got a ride on the meat truck that always drove to Houghton after his deliveries in Columbia. The man that ran the Houghton hotel took me the rest of the way to our farm.

One of the spring events for the graduating seniors was the Junior-Senior banquet. Various students performed songs and skits. One of the seniors circulated about the tables singing They Call Her Two-Ton Jessie From Tennessee, a George Burns patter-type song. Absolutely, politically and sensitively incorrect and none of us knew it.

Graduation ceremony for our Class of sixteen students was held in the Congregational Church. The relatives sat in the pews and watched their sons and daughters walk down the aisle in the awkward, halting step that some teacher thought was important and that none of us did well. We sat behind the minister’s pulpit and listened to the speeches delivered by the Principal and the Valedictorian. After I gave my Salutatorian speech, we were off for the prom dance. The High School gymnasium was draped with gold and maroon twisted ropes of crepe paper for the occasion. A small band played dance music and there was plenty of room on the dance floor for the twenty couples attending. At the end of the day, sixteen more graduates went out to change the world.

I was 17-1/2 years old at graduation time and planned to enroll in Business College to acquire skills that would qualify me for a coveted office job. My sister, Verna, had a good job at the Department of Internal Revenue in Aberdeen, the largest city in our part of South Dakota. It was about forty miles from home. Her stable employment qualified her to cosign the $100.00 loan I needed for Business College Tuition. She agreed to this, and made my Business College training possible.

I was introduced to the world of suits when I went alone to the Columbia State Bank to borrow the tuition money. I had never sat across a desk from anyone I considered as important as Mr. Huey Jones, manager of this small town bank. He was a short, round-faced man and he wore a suit to work. At that time in my life I knew only two other important people that wore suits to their jobs: the Minister of the Congregational Church and the Principal at Columbia High School. I was honored and awed by the presence of this person who’s job was so important it required him to be splendidly groomed. My brothers wore suits to the Saturday night dances but they performed their daily work in overalls. My father felt dressed- up wearing a suit jacket over his brand new overalls when he went to Aberdeen, but this banker wore a full suit to his job at the bank, every day of the week.

I told Mr. Jones how much money I needed and he agreed that Verna could cosign the loan. In addition to his managerial duties, the nattily attired Mr. Jones, happened to sell insurance. There I sat, a trusting, gullible girl who believed that every adult was helpful and knew everything there was to know. I knew they were eager to transfer all their knowledge to my fertile mind so I could move on to a rich, fulfilled adulthood, like theirs. Mr. Jones, in his sartorial splendor, was preparing to do exactly that. I was a blank book and he was about to mess up the first page.

He sat there in his suit, his hair flattened and shiny from a heavy Brylcream application, and told me he would be happy to loan me $100.00. His face clouded as he related a small problem: how would he be sure, he said, that Jean Mertz, a seventeen- year-old, would be alive at the end of the year to pay off the loan? Seventeen-year-olds were evidently dropping like flies. He seemed to have forgotten I had a cosigner. He explained that the only way for him to protect himself in the event of such a calamity was for me to buy a life insurance policy with an annual premium of $26.00. He easily convinced me of his wisdom. The least I could do to protect this considerate man’s investment in my future was to add the insurance premium, plus the interest to my $100.00 loan.

Finding myself still alive a year later, I paid off the loan and insurance fee. Since there was no longer a need to protect the banker’s investment, I did not renew the insurance policy. Thanks Mr. Jones, for imparting to me this sorely needed wisdom. If this had been a Junior College course it would have been entitled “Questionable Financial Aid, - Part I”. Experience really is a good teacher, but is sometimes the most expensive.

I moved to Aberdeen and shared room and board with Verna. Her landlady, Mrs. Milbrandt, a cheerful woman with a German accent, treated us like her family. It was war time and her husband was working as a carpenter in Washington State. He was building government housing for the defense workers of the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard.

Verna taught me the intricacies of big city living, and probably opened her purse for more things than I remember. The homeowner next door had converted his living room into a hamburger joint and we occasionally enjoyed his big, fat, ten- cent hamburgers. There were fifteen-cent movies at the theater a couple blocks away and foamed-over root-beer floats at the Five & Dime Store over on Main Street.

Aberdeen Business College taught Dictaphone operation and shorthand. Mr. Gabbard, the manager of the school, was a master at garbling, mumbling and slurring his words. But, he did have a nice rich voice. The combination of his ego, position and slovenly diction assured that his would be the voice used in all the Dictaphone cylinders from which the students transcribed their lessons. That old technology was indeed a challenge. No audiotapes and no sensitive earphones. Nope, just Mr. Gabbard’s unintelligible baritone voice as he murmured and gabbled his way through recording after recording. It was necessary to reverse and play back the cylinder many times to correctly type his words in a business letter format.

We studied Bookkeeping and Business English. The English teacher gave a daily list of twenty new words and required us to sit at our desks in her classroom and write each word ten times. I liked it just about as well as I liked Penmanship and Spelling in those grade school days when I occasionally feigned illness. There was no one to rescue me from Business English and take me home on a horse.

During the last week of each month, the students welcomed the chance to do real office work for pay at the Socony Vacuum Oil Company. We were paid twenty-five cents per hour to type the name and address headings on their customers monthly statements.