PA and MA

Ma would find a use for any fabric scrap at our house, no matter how shabby or worn. She ripped worn cotton clothing, denim overalls and blankets into one inch wide strips. After sewing the strips into a long continuous strand, it was wound it into a large ball, eight inches in diameter. A local weaver wove these multicolored balls into rag rugs that were used throughout the house. Wooden apple baskets filled with carpet rag balls were stored in the attic.

She saved the white string used by merchants to wrap purchases and wound it onto its own little ball. The many little hands using pieces of string prevented the ball from growing very large. Tinfoil wrappers from tea and gum were pressed into a silvery wad and used in craft projects. Discarded paper gum wrappers were folded into zig-zag belts and garlands. During the depression Ma made chenille bedspreads from bleached heavy feed sacks sewn together into a bed size. She hand-stitched a design, making 1” stitches, through the fabric using a multi-filament, thick cotton yarn. When the large stitches were clipped they fluffed into plume-like tufts. She made muslin feather quilts and bed pillows from our own chicken and duck feathers. Sacks filled with feathers flopped around on the clothesline for months at a time until she had time for that project, or perhaps the feathers needed time to clean themselves in the open air.

Fancy embroidered doilies and lace dresser scarves were laid flat on a padded brocade square and then rolled like a cinnamon roll. This ‘Fancy Work Roll’ was stored on a high closet shelf and occasionally brought down and unrolled for viewing. We all gathered around to see and touch the lovely things before they were carefully rerolled and returned to the shelf. She saved these treasured linens for good. Unfortunately, a sniffing mouse found something he liked about that roll of fancy linens. He ate through the outer brocade and every piece of ‘fancy work’ that got in his way until he reached the desired delicacy. He left a few droppings and some yellow stains. This ruined most of what Mother had in that roll. She enjoyed getting out those lovely things and looking at them once or twice a year. It probably made her feel good to see the nice things, just like it did for us kids.

Beginning in 1953, Mother began yearly winter trips to visit her daughters living in warmer areas. She missed very few years visiting Verna and Ed in Utah, Joyce and Jim in Arizona and Lyle and me in California,. She arrived in California with a nice tan she got while in Arizona, a tan obtained in the pursuit of pleasure instead of hard work. It was scarcely noticeable on her olive skin but she sat on the front porch in our Northern California winter sun attempting to preserve that golden Arizona glow until she returned home. There would be no mistaking she had spent the winter somewhere besides South Dakota.

She told me the unique ways she hid her money at home. She accumulated money from selling eggs to farm visitors. Storing the cash in a house that was never locked worried her and inspired her to be quite creative in finding hiding places. Any hopeful thief was in for a difficult time at Ma’s place. When she came to visit in her later years, I always inquired of her current hiding place, knowing it would be difficult to find her assets if something happened to her.

The first time I asked about her private hoard was the year she put it on the floor under the edge of the linoleum. Her ingenuity was impressive, but not surprising. A couple years later she said the money had been put in a sock and stuffed in the toes of rubber winter overshoes in her closet. Another year she stored money in a canning jar submerged in a 5-gallon crock filled with white baking flour. Anyone taking money from that spot was going to make one big floury mess and leave magnificent tracks that would send Sherlock Holmes into ecstasy.

One February we picked her up at the San Francisco airport for her annual visit. She was in her mid-80’s and still very active. We hadn’t gone ten miles down the freeway from the airport when she leaned toward me and said “Guess where I have my money this year.” It was quite obvious from the sparkle in her eyes that she could hardly wait to supply me with the answer to her own riddle. Ever since she had a radical mastectomy in the 1950’s she usually wore a bra with a pad in the empty cup. Not that day. She reached down the neckline of her dress into the bra pocket where the pad would have been and pulled out a bunch of one-dollar bills banded in a tight little roll a couple inches in diameter. We both laughed.

Raising a family of ten children is a formidable task at any time. To bring them up on a South Dakota farm during the depression presented my Mother, Hilda, with a series of challenges that she met with vigor and imagination. Ma could whip out Pa’s hacksaw and bring an iron bed to its knees while the supper potatoes were frying on the cook stove. There was no piece of furniture on our farm that was safe from her attentions. It seemed that with Pa’s hammer and saw, wielded with the force of her own determination, Ma would bring our farmhouse to the cutting edge of home design.

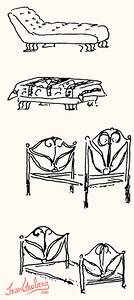

In 1932 the Sears Roebuck catalog featured the ‘Hollywood’ style bed, with its low headboard, as the very latest in bedroom fashion. It was then that Ma began her home decorating career, hacksaw in hand, as she converted her own iron bed to the popular ‘Hollywood’ style by cutting its legs down to mere stubs. This modernization pleased her six daughters so much that she immediately shortened legs on the three iron beds in the two upstairs boys and girls bedrooms.

Chests of drawers were next to bear witness to her skills and within days all were resting fashionably legless on the floor.

A worn, seven-foot, leather-covered chaise lounge with a hump at one end was destined to be Ma’s next project. It had been an unclaimed railroad shipment until Pa, who was the depot agent in his younger years, decided to give it a home at our house. Ma knew that valuable living room space was squandered by the useless hump and now she had a solution. With her recent successes behind her, she attacked that lounge like a practicing Civil War surgeon. With the hump amputated and using nails found in Pa’s machine shed, she grafted new legs and finished the job by covering the wound with a carefully tucked and folded Indian blanket.

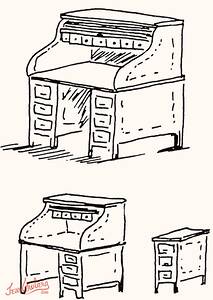

By this time she was not only quite experienced with the saw, she could also swing an effective hammer. After a few months spent pondering her next move, Pa’s roll top desk caught her eye. Already it had been providing double service. In addition to standard desk duties, it was used as a rudimentary pre-incubator. In the spring when the ducks and turkeys began to lay their eggs, Ma stalked the elusive hens to find their hidden nests in the willows and tumbleweed. The treasured eggs would be gathered and stored on Pa’s desk, laying in neat rows within sawdust-filled, cardboard trays, their numbers growing daily. When the weather was just right, the eggs would be returned to setting hens for hatching. Ma decided this big desk could use a few improvements. Laying it on its back she removed one of the end panels. With her trusty saw, she cut off one of the drawer stacks that flanked the knee hole and then shortened the rolled top. After pruning the pigeon hole section, the side panel was reattached to the abbreviated desk. The liberated drawer stack “fit just right” as an end table by the remodeled couch.

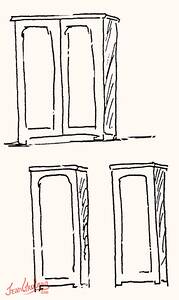

With her skills proven, Ma’s confidence grew and she selected a large upstairs armoire for her next project. It was almost five feet wide and had been strategically placed at the top of the stairs to prevent any kids from tumbling down the otherwise unprotected stairwell. Ma decided to put this cumbersome piece of furniture to better use by cutting it in two. Under her refined abilities, the separation was successful. With planks from the fence to cover the open sides and to make shelves, the two new cupboards began service for linen and pantry storage.

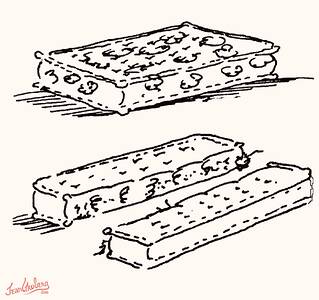

Over the years, Ma’s unique talents blossomed like wildflowers in a barren pasture and her accomplishments on our farm gave it a personality uniquely its own.. She was a fount of resourcefulness, nothing was thrown out if there was still a use for it and Ma could find another use for anything. She sewed dresses and skirts from old woolen shirts, smaller coats were made from larger worn coats and one good pair of stockings from two frayed pair. Old mattresses, cut in half lengthwise, were converted into portable sleeping mats. Empty sardine cans and Pa’s Prince Albert tobacco tins, carefully tucked in the dirt, made decorative borders for her flower beds. When asked to comment on her tremendous labors of these decades she would quietly murmur, “Oh, I kept busy.”

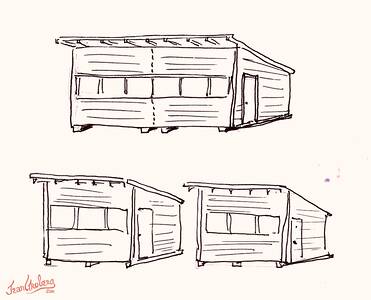

She was nearly sixty when she began what was to be her largest project. She had learned that Pa was planning to sell the brooder house to raise some badly needed money. The brooder house was an 18’ x 20’ flat- roofed structure built on a wooden beam foundation. – Ma’s newly-hatched chicks, ducks and turkeys spent their first weeks in this building where they kept warm clustered under a wide hood that surrounded a small kerosene stove. When mature they furnished food and income. – Ma was not about to give up this needed building, so without a word to Pa, she took action. The next morning she carried the saw along when she made her way to the vegetable garden. As she passed the brooder house, she walked around to the back side, selected a point about halfway down its length and began sawing. After a few minutes, she set the saw down, went on to the garden and returned to the house with her apron bulging with vegetables for the noon meal. The next day, and every day thereafter, she followed the same pattern. It was a race between Pa’s procrastination and the limited amount of time she could spend on it. As the weeks went by, she cut through that wall, the roof, the floor, foundation and then the front. She could do no more. Several days later, Pa came in from the fields for the mid-day meal, tied his team of horses in the shade and gave them their water and oats. She was watching from the kitchen window when he walked by the brooder house and she saw him pause. He had noticed the saw-cut in the front wall. What would he do? With his stained felt hat pushed back on his bald head, he slowly circled the building, studying it with great interest. The chickens scattered as he walked across the hot, dusty yard toward the kitchen. After finishing his meal, he pushed his chair from the table, hooked the heel of his shoe over the chair rung, and leaned back. “Hilda,” he said, “Have you been doing anything to the brooder house?”

“Well, you know, Linus,” she replied, “That building has always been too big, so I sawed it in two. Now I’ve decided to keep one piece and I need you to hitch the team to one section and pull them apart.”

With nothing more to be said, Pa dragged the pieces apart. Ma boarded up the open sides of the buildings. Her saw and tenacity had saved her a brooder house that she used for years to give her chicks a start.

Years later, when I had gone back to South Dakota for Pa’s funeral, my sister and I lay in the darkness in our old upstairs bedroom. We looked down into the shadowy farmyard and could see Ma’s rugs, made from worn overalls, hanging on the clothesline. We watched them flapping in the restless prairie wind, shared memories of Ma’s remarkable modifications and we laughed until we cried.

In my mind I can picture her now, saw in hand, cutting the tops off the Pearly Gates to make a fence for her chickens in the sky. What a woman!

When I was six or seven years old, during the early 1930’s, I became aware that Pa drank. His illness caused misery for the whole family and especially for Ma. It gave her one more thing to worry about, and she had advanced degrees in worrying. We didn’t have a car and were four miles from the nearest town.

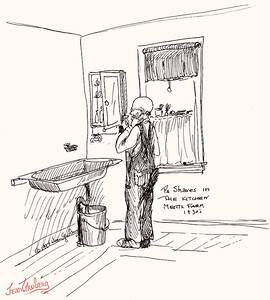

When Pa wanted liquor he would find his way to the town of Houghton, population 107, by walking, hitching a ride or a combination of both. He would sometimes stay at the Houghton pool hall until after dark waiting for a chance ride heading east of town. Some winter nights Ma would fix supper for us kids and as soon as darkness fell she took up her position at the west dining room window at the foot of the stairway. From this point she could see the few lights of Houghton. When she saw car lights driving east from town she worried out loud. She watched until the lights briefly disappeared behind the trees at a crucial corner two miles east of town. If the car lights emerged going north, Ma would wonder if they had stopped behind those trees and dropped Pa off. From that point he would then have to walk almost two miles home--or maybe he wasn’t in that car. She worried out loud “- ah--there’s another car coming out of town-- oh, it turned south at Kimball’s farm---a good sign-- maybe someone was bringing Pa home.” Thus she murmured and worried as she stood at the window. Sometimes it was two hours before a pair of lights somehow produced the man she was waiting for.

Many autumn and winter nights it was dark when he came home from these excursions. He would eat his fried potatoes and whatever food remained and then go out to milk the cows. Ma then had another torturous hour of worry after he picked up the kerosene lantern and stumbled through the darkness toward the barn to do chores. She now took up her vigil at the north window with Joyce and I at her side. We were getting lessons in Worrying First Class. She verbalized her concern as she watched the light of the kerosene lantern in Pa’s hands trace an erratic path toward the barn. Surely, she murmured, he was going to set the lantern down, trip on it, spill kerosene on the straw on the barn floor and once the barn became a flaming mass he would never get out alive. These must have been terrible evenings for her as she stayed in the house with her four youngest. I was 9, Verna was 11, Joyce 7 and Bruce 5.

Sometimes she would be milking the cows herself when he arrived home. If she was on her way to the barn when he arrived, he would insist taking the lantern and milk pail from her hands and doing the milking. Ma would worry about him again.

When Pa was drinking Ma knew where to find the bottles. She was too resourceful to throw them out, and would pour some of the contents into a gallon glass vinegar jug in the cellar and then replace the bottle. Sometimes it was whiskey, sometimes it was peppermint schnapps. No matter what the label, it was liquor and it all was poured into the same jug. When Pa needed to taper off his drinking, Ma would measure off small quantities of this strange cellar brew. I felt sorry for Ma, the life she had, full of worry. She deserved an easier life. I felt sorry for Pa. He was a loving, intelligent, creative and kind man who seemed unable to get control of this debilitating addiction.