Life in Bremerton

My first backpacking trip to Flapjack Lakes and Mount Gladys in the Olympic Mountains took place in August of 1946. I went with Jane and the Benson family for this ten day trip. One morning after breakfast as we were cleaning camp, a group of about 15 enlisted Navy men and their officers on a survival bivouac walked into our camp. They told us the atom bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima the day or two before. This was exciting and surprising news and we looked forward to our return to civilization and the possible changes. Japan had not yet surrendered.

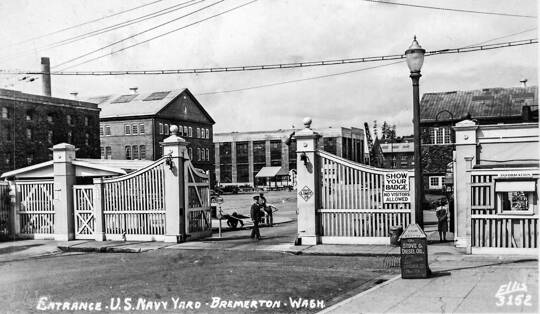

We were back at work only a few days when the announcement came that the war was over. The Shipyard released all employees immediately and Marge and I walked out the Shipyard gate into the middle of an impromptu celebration on the main downtown avenue of Bremerton. Crowds in the middle of the street had brought traffic to a standstill Church bells were ringing, horns honking, buses were unable to move. There were conga lines of workers, secretaries, seamen, old people and young people screaming and yelling with happiness. Big wrap-around hugs and kisses were exchanged freely between strangers, and the young Navy men were grabbing and kissing the girls, any girl. Marge and I were astonished by the cacophony and the joyful release of emotions. We joined a conga line that pushed and snaked through the mass of people and then got on a bus to go home. The bus struggled through the happy streets, even the driver was smiling as we inched along.

Once in our apartment we talked and began to assimilate what had really happened. This is what we had been working for, the end of the war. From the comparative quiet of our neighborhood in East Bremerton we could hear the sounds of marathon horn honking and downtown church bells drifting across the inlet.

The peal of the church bells were noticed by Marge who felt the church bells were calling us. I can’t say I felt they were calling me, but she felt we should go to church. It was mid- afternoon when we entered the small white church a couple blocks away. We had never been there before. The church had not had time to prepare an organized program to celebrate this event. A handful of people sat helter skelter in the pews talking in muffled tones. Some meditated for a short period. After a respectable time we left.

The day was not over for us, we boarded the Seattle ferry to see how a big city would celebrate the war’s end. The one-hour ferry ride to Seattle during the war years was an interesting experience. Shortly after leaving Bremerton it sailed through a narrow inlet between Bainbridge Island and the mainland. This passage was controlled by two Navy net tending vessels moored in the center of the inlet. Each ship trolled nets deep below the surface. Their purpose was to prevent enemy submarines slipping through the channel and gaining access to the many warships being repaired at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. When the ferry reached the nets it would blow it’s whistle, and the Navy boats would each drag the underwater nets toward opposite shorelines to open the channel. After the ferry passed, the nets were towed back to the center and the net tenders resumed their guard position.

Seattle was celebrating big time. The streets were gridlocked and the sounds of hundreds of car horns reverberated among the taller buildings People were wild with joy. We joined the mass of people that filled the street and sidewalks of Fifth Avenue. Like in Bremerton, it was a tremendous crowd of euphoric, shouting, dancing, hugging and kissing people. There was no doubt some celebratory drinking but I do not recall drunks. I remember the exhilaration and the wild, silly exuberant behavior of the happy crowd. There was dancing, pirouettes, more hugging, jubilant jumps, waving and dancing in the street. A flatbed truck passed before us, its platform crowded with singing celebrants. Strangers aboard the flatbed reached down, we grasped their hands and were hoisted to the truck platform becoming instant old friends for the whole mile that we stayed aboard. We viewed the extraordinary scene below us and joined our new companions in song as the truck inched up Fifth Avenue. At one clogged intersection, we dismounted and rejoined the street crowd.

As twilight dimmed the beautiful evening, we pushed our way through the throngs and made our way to the ferry depot. Once aboard the Bremerton ferry, we joined other returning celebrants along the railing of the top deck to watch the ferry leave the pier. The Seattle lights grew dimmer as we sailed out of Elliot Bay and the sound of honking horns and pealing church bells slowly faded. The nearby tree-studded hills were silhouetted against the fading light as we entered the shipping channel by Bainbridge Island. It was so peaceful. Only the throbbing motor of the big ferry and the swishy noise of the boat’s wake broke the sound. It had been an unforgettable day! The war was over.

Marge and I moved to a small four-room furnished house about a half-mile walk from our jobs. An oil-burning floor furnace supplied heat and we cooked on a long legged 1930’s style electric stove. There was an empty one-room cottage in back and an aged apple tree out front. We had graduated from basement apartments and were actually living above ground level and we loved it.

The Shipyard no longer needed 30,000 employees. The ‘rif’ (reduction in force) pink slips were gradually distributed as the downsizing began. Marge was concerned her job might be eliminated so she resigned and looked for work outside the Shipyard. She began commuting the one hour ferry ride to Seattle to work as a stock girl at I. Magnins exclusive clothing store. Even though the employee discount was attractive, I was quite surprised when she paid $200 for a fur coat on the installment plan.

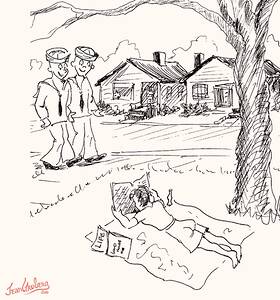

She was very shy, one need only ask her, “Marge, what makes you blush?” and her face would immediately turn scarlet. I admit that I teased her a bit. Our little house was two blocks from the city park. It was not uncommon for servicemen on liberty to pass by our house on their way to the park. On one of those rare sunny afternoons, Marge put on a pair of shorts and was laying on a blanket in the front yard. I was in the house and noticed two young sailors approaching. Marge noticed them also and immediately lifted her magazine high above her face and pretended to read. They glanced at her as they walked by and she would not look up.

After they were about ten steps past her, I stood out of sight and gave a wolf whistle from inside the house. The happy sailors immediately spun on their heels and walked back to Marge and asked if she had whistled at them. Her face turned scarlet, she picked up her magazine and blanket and hurried into the house and slammed the door. She was furious with me. The sailors looked puzzled, and then went on their way.

But, back to the fur coat. It was a surprising purchase for a timid girl who did not enjoy the focus of other people’s attentions and who was anything but flamboyant. It hung in her closet a lot and I am sure she felt everyone was looking at her when she wore it on dates those few times. When she decided to return to her home in the Black Hills of South Dakota, she felt her parents would be critical of this indulgence or, worse yet, might think she accepted an inappropriate gift from a boyfriend. She sold it for $50 to a man in the office who bought it for his wife. I imagine that fur coat would have felt quite nice after she returned to those South Dakota winters.

With Marge moving back to the Midwest I immediately looked for a new roommate and found two. Adelade was from North Dakota and worked in the Post Office in our office building. She was living in a small apartment with Marie, a telephone operator for the Bell Telephone Company. They were great roommates. We were congenial group, all between 20 and 23 years of age.

Marie’s telephone job required peculiar hours and occasional split shifts which meant she would work four hours, go home four hours, work four hours more and then have 12 hours off. It was a terrible schedule, sometimes she got home at midnight. It was hard to keep track of her hours and it seemed that she was always in her blue bathrobe, either preparing for bed or just arising. She and her many telephone operator friends were a lively group. They trailed off into hysterical laughter when they shared hilarious tales of ‘ number please’ experiences. The telephone operator would usually listen to one or two words of newly connected conversations to assure a successful connection. Operators were carefully monitored to prevent lingering and listening, Jean Mertz Groberg 153 but sometimes they listened a little longer if a phone conversation got off to an interesting beginning and if it happened to be a slow night on the job. They enjoyed sharing their telephone connection tales.

Our sleeping accommodations for three was simple, two shared the double bed in the bedroom and the third person slept in the living room on the fold-down davenport. It was disassembled each morning and the bedding stored in the cavity below the seat. We took weekly turns sleeping on the davenport, the exception being that the last one to come in from a date slept there, no matter who’s turn it was. This freed the living room for the last girl in at night to invite her date in out of the rain for coffee if she chose to do so..

We saved the grocery sales slips and split the costs at the end of the month. We usually ate meals together, however Marie’s erratic hours frequently meant she ate what we saved for her or what she cooked separately. We were specialists at putting chipped beef, tuna and canned asparagus in a sauce and serving it on toast.

One twilight winter evening there was a wet snow falling. Adelade and I came home from work at the same time and had both forgotten our keys. The only way into the house was through the bedroom window. Anxious to accommodate my new roommate I volunteered to go through the bedroom window along the side of the house. We found something to stand on. I didn’t want to soil my new rose colored coat on the sooty wet window sill, so I handed it to Adelade. My good dress was too nice to sacrifice to the grimy sill, so I stood in the snow and removed it also. The big snow flakes melted as they hit my bare skin. I looked down at my new satin slip which was likely to get snagged on the worn dirty sill. Well, not if I took it off - and the nylons too. By then we were both laughing so much that we were being silly. Stripped down to the bare necessities I went through the window head first. I wonder if the neighbors across the fence saw us.

Adelade bought an old wringer style electric washing machine with a green enamel tub that we put it in the basement by the cement laundry tub. The laundry dried on the backyard clothesline during good weather and in the basement on rainy days.

The damp cottage in the backyard had a bed and mattress that we used for some slumber parties. I never could resist a blank wall, and the cottage was the perfect place to paint life size footprints that walked up one wall and separated as they crossed the ceiling. The right and left footprints walked down separate walls. An airplane was skywriting ‘Coca Cola’ on the ceiling. Silly, but fun.

I was getting anxious to find work outside the Shipyard in 1946. I liked living in Bremerton and knew that if I delayed looking for work in the business sector, the few jobs would disappear to other job-seeking ex-Shipyard employees. The Gray Robinson Portrait Studio had a fine reputation and it looked like an interesting place to work. I knew nothing about photography, but hoped for some office work. During the job interview, I showed Mr. Robinson the portfolio of drawings and artwork I had accumulated while passing time at my desk in the Shipyard. He was building a new state-of-the-art Portrait Studio a block away and his present studio would become his exclusive children’s portrait studio. I was hired as bookkeeper and relief receptionist for the new location. Showing the drawings turned out to be helpful for he was planning to have murals painted on the walls of the children’s studio and he needed artists. He already employed three girls with art training so there was plenty of art talent in that studio. I was almost 21 years old and had never worked around creative people like this. It was a stimulating change from the civil service work in the Shipyard.

Once my Shipyard resignation was submitted, the office personnel once again went through the ritual of collecting a dollar or fifty cents from everybody in the office to buy a ‘going-away’ present for me. Over the time I had been in the Yard, I had donated lots of dollars and quarters for gifts to the many people who had departed before me. It was now my turn to receive. On my final day, the cake and coffee were served during the coffee break and I was presented with a silver plated Oneida flatware set in a walnut box with a velvet lining. A nice gift. I probably didn’t deserve it but was content to wallow in my good fortune. There would less people to participate in these collections as the staff dwindled. The last ones departing after me were probably fortunate if they received a book or a glass dish.

I was very excited on my first day of work to at the portrait studio. It was a few months before my 21st birthday. The new studio, a block away, was not ready for its grand opening and the staff for both studios were walking all over each other in the cramped old studio. We had four photographers in the building, two receptionists, a bookkeeper, two printers, one photo coloring artist and a retouch artist. Fred left occasionally to go out on location to commercial jobs during the day.

Mr. Robinson, in his mid 40’s, was a handsome, nicely- dressed fellow with a mustache. He was a cheerful man with a very engaging personality and a heavy smoking habit. He gloried in being King of his little fiefdom. He lived on a nearby island. If he missed the ferry home he knew where to get a drink while waiting for the next ferry, or the one after that, and perhaps sometimes the one after that.

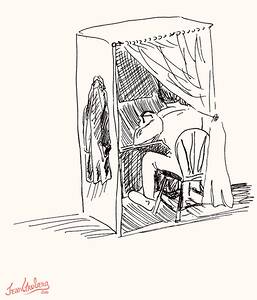

Jim, the retouch artist had a grim, lonely job. He sat in complete darkness in a secluded plywood booth carefully scrutinizing the smoky negatives that were centered over a brightly lighted 4” hole on his slanted light table. A canvas curtain shut him off from the lights in the finishing room. He spent the day obliterating facial blemishes and wrinkles on the portrait negatives of our customers. Using pencil holders with long, changeable leads, he drew tiny little figure 8’s and s’s on the dull side of the negative. It was precise work that required skill. A careless job showed up on the enlarged picture. He was a master at this craft and he charged by the ‘head’ for his work. It is no wonder he occasionally drank too much. He was originally from New York and lived alone in a small waterfront cottage that was built on pilings over the tide flats, several steep wooden stairways down from the street level. It was not surprising when we heard that he tumbled down the stairway one night after an evening of drinking. After a few days in the hospital he was back at work.

The printer was a large grandfatherly man who walked through the darkroom curtains with his rubberized apron smelling of photographic chemicals. He was assisted by a plump, plain girl in her twenties. She, too, had a cheerful disposition and occasionally joined in the finishing room banter. Even Joe, isolated in his dark retouching booth, would call out a contribution to a conversation taking place outside his cubicle. He overheard many conversations by people who had forgotten his quiet presence behind the canvas curtain.

There was only one way to get a color portrait in 1946. It had to be hand-colored and that was the job of Marion. She was a talented girl, also in her early twenties who could bring those gold-toned portraits to life using small tubes of special oil paints. She did outstanding coloring work for both Studios. The word ‘creative’ was invented for this person who had artistic curiosity in all fields throughout her life. She dated Jack, one of our studio photographers, a romance and marriage that has been going on for fifty years.

Fred, the outside photographer, had interesting stories to tell when returning from some commercial jobs. One job took him to the funeral home where an elderly eccentric woman wanted photographs of her deceased son as he lay in the casket. The funeral director was upset because the old lady kept caressing the deceased and rubbing off the makeup. One rainy Washington day he was photographing informal candid shots at a wedding. The most interesting picture of all was the one the bride never saw. To escape the rain, she had hurriedly gathered her voluminous satin skirt to crawl into the back seat of the wedding get-away car. Fred, ever conscious of getting his equipment wet, lifted the camera over his head, pointed it in the direction of the action and grabbed a fast blind shot of the departure scene. He was trusting to luck that something useful might be captured on film. The printed proofs revealed the full length of the back of the bride’s leg including the stocking top and garter -- no panty hose in those days. We laughed about it at the studio, but the picture was withheld from the presented collection.

Ellie, an art major from the University Of Washington, was a receptionist as well as a very capable photographer. She and her husband had purchased a topless, army surplus, olive colored army jeep and we drove about in it. Her husband was covering the Indochina war in Laos. He wrote a book about this period when he returned to the states, I went out to their place and did some typing for him.

Marge, about 24, was a graduate from Chouinard Art School in California. She was a fine artist and an exceptional salesperson. She could easily get a customer to spend two to three hundred dollars for photographs and make them positively glow with happiness at this big expenditure. She was definitely good for the business. She was an only daughter and had a wardrobe of lovely clothes that she wore well.

George was a tall slender photographer for the Children’s Studio. He kept his hairline mustache fastidiously trimmed, in fact he gave the impression that he did everything meticulously. Even his speech had a measured, precise manner.

There was a lot of creative talent in that studio, both studios were well-staffed. Ellie and I submitted drawings to Mr. Robinson for Children Studio murals. I was assigned to do a mural of the Old Woman Who Lived In a Shoe while Ellie was painting the Cow Jumped Over The Moon. We snapped our chalk lines in 12” increments and began the transfer of our drawings to the walls. The murals were completed before the new studio opened.

Little did I know how important my 21st birthday would be to Mr. Robinson. I was now old enough to have a permit that allowed me to buy rationed liquor. He paid for my permit and made certain that I regularly purchased my allotted quota of Three Feathers or Four Roses Bourbon, the only choices available in the bourbon department. I didn’t know much about either so I just bought what he ordered. Choices were limited as some liquor brands hadn’t ‘returned from the war’. Ration coupons would buy a couple fifths a month at the package stores operated by the State of Washington. To buy a bottle involved two counter people, one to take the coupon and deliver the liquor and the other to take the money.

Buying mixed drinks in public places was also complicated. There were many beer halls, but hard liquor could only be sold in licensed ‘bottle clubs’. The Bremerton City Club, located above the City Hall, was the popular ‘bottle club’ for drinking and dancing. This unique location placed the Police Department right down the stairs. Payment of a token fee made you an instant member. Once a member, you furnished your own bottle of liquor identified with your name, and presented it to the bartender. He stored it behind or under the counter, and then poured your drinks from this marked bottle, charging a set-up fee for each glass served. One wondered how carefully he reached for those private bottles that were stored out of view of the persons sitting at the bar.

The club occasionally featured live music on weekends. It was considered more of a downtown watering hole in spite of the efforts of the management to jazz it up with live talent, some young and some slightly worn. Fifi D’Orsay, a French chanteuse well past her prime, performed there. Eddie Peabody, a diminutive fellow who billed himself as the ‘Banjo King’, had been famous years before he performed in Bremerton. He played his banjo from an instant stage created among the dining tables. He just sat his chair on a dining table, up close and personal, and played his lively music.

Mixed drinks were also available at the Officers Club to commissioned officers and their guests. This club, on the hill in the Shipyard, was well known for its outstanding Friday Night Buffets, and dancing to a live orchestra. The Elks Club and the Golf and Country Club were popular watering holes also requiring membership.

The Elks Club was only a couple blocks from the studio. They had a few slot machines, as was permitted in private clubs. Mr. Robinson’s mother was an animated little lady who dressed nicely. She loved to spend her time there playing the slots. When she ran out of money she would come to her son’s portrait studio and ‘cash’ a check for $20.00, with the admonition NOT to cash it. I was the bookkeeper and the only way to hold these checks was to put them under the change tray in the register every morning as part of the daily cash. There were a few times when she had three or four checks still awaiting redemption under the change tray, and she would show up and add another to the collection. When this procedure eroded the available money allotted to the cash register, Mr. Robinson took out his wallet, redeemed his mother’s checks, and tore them up.

At one time she decided that I, age 21, would be a match for her bachelor son who was in his mid-thirties. I was invited to their house for dinner so I would get to know him. I didn’t know how to tell the boss’s mother that her son was too old, and that I was not interested, so I went there for dinner. Everything was very nice and proper. I didn’t date her son, who seemed like a very nice fellow. I presume he felt the same as I did, in reverse. I did come away with her lovely recipe for Date Torte that I still use.

Mr. Robinson’s new studio was smashing. Its huge camera room featured a balcony that swirled into a curved stairway that was designed as a place to pose groups of people, brides and ladies in long formals. There were two finishing rooms, one with a balcony, a fine darkroom, print room as well as an elegant sales salon and lobby. Mr. Robinson knew how to do things in style. The grand opening was attended by all the downtown notables.

Being pulled from the sterile Shipyard civil service culture out into the social whirl of downtown was an exciting change for me. I loved it. Mr. Robinson’s membership in the Rotary Club, Elks Club and Golf and Country Club gave me an opportunity to design a number of invitations and programs for some of the special functions of these service organizations. These little art jobs were welcome additions to bookkeeping and receptionist duties.

The Studio had a good reputation and did very well. The first Christmas season had us all working until 2 a.m. in the finishing room. Marie, a tall angular woman receptionist, was a master when explaining delivery delays at the front counter. She lightheartedly gave absurd excuses such as ‘the longshoreman strike in San Francisco’, or ‘oil shortage’ and then give the customer a big grin. They walked away disappointed, but with a smile.

Shortly after moving to the new Studio Mr. Robinson purchased a prestigious Portrait Studio in the Olympic Hotel in Seattle and while spending time in the Seattle area he added another business to share our luxurious Bremerton studio. He purchased a Modeling School franchise and hired a director for it. She was a very attractive woman, in her late 30’s or early 40’s, who commuted daily from Seattle.

All female Portrait Studio employees were encouraged to sign up for the first Modeling School Class, no charge. Mr. R. was making certain that all the young women that walked through his reception lobby would be good representatives of his businesses. He also wanted to encourage the Model School director by providing students to fill those first modeling classes -- and we were it. These self-improvement classes were called “Charm School”, a cloying name that makes one think of the old South. It seemed like a dumb name, even at that time. We learned about makeup, walking, basic etiquette, how to enter rooms, how to sit, stand, remove coats. All that sort of thing. A general rounding out of social graces, nothing painful or harmful. Ah, our Studio was about to be graced by young women who walked beautifully and wore their makeup JUST RIGHT. We each bought a round leatherette hat box with a handle and hinged lid that models carried in those days. It was filled with makeup, makeup capes, brushes and sometimes even a hat.

The leaders in fashion had decreed the “New Look” in 1947. The war was over and fashion could kick up its heels a bit and use more material. Wartime clothing was not wasteful with fabric. Even men’s suits gave up cuffs during the war because they used extra fabric. The ‘New Look’ meant longer skirts, pencil slim and flared, that flirted with the ankles. Black suede high heeled pumps, some with ankle straps, wrap around jackets and button-less swingy coats were fashionable. Hats and gloves were the finishing touch to any outfit.

We participated in many fashion shows to advertise the Modeling School. Usually the Modeling School Director asked exclusive dress and shoe shops in town to loan apparel. Since no well-dressed woman in those days went out without a hat, it was off to a contributing hat shop to select the proper hat for each dress. We were all over town by the time we put our outfits together for a show.

She once arranged with several beauty parlors to style the models’ coiffures for one show. In return, the salons were to be listed in the program credits. The hairdressers outdid themselves, and each other, as they demonstrated their skills with pin curls and hair lacquer. The hairdos coming from their shops were memorable, for sure. The damp Puget Sound atmosphere could never undo the handiwork of these pin curl wizards. We left the salon with our hair rigid with hair lacquer squeezed from a red rubber bulb that made coughing sounds as it spit droplets on our hair and enveloped us in a bubble of lacquer fumes. We were warned to protect these coiffures with silky caps when we pulled garments over our heads.

Unfortunately, on the evening of the show we learned that the hats we had selected early in the week were not compatible with the lacquered hairdos created by those salon whizzes on show day. There was hostile combat between the hat and hairdo; usually the hat won handsomely and the hairdo flattened in defeat. There were probably some very unhappy hairstylists attending the performance. Some downtown businessmen, in top hat and tails, performed as male models and escorted us down the runway. (A sure way to get attendance from that sector.)

One winter night we modeled in a Ski Show during intermission time at the Perl Maurer’s Friday night swing dance. We were all warmly dressed in brightly colored ski togs with the exception of my tall friend, Marion, who modeled the most remarkable outfit in the show. It was a flame red ‘ski-o-tard’ made of a knit material and was carefully selected to be the final ensemble presented. The upper part was like a long-sleeved leotard but the bottom section was merely a long panel that dropped from the front waistband. It was pulled up tightly through the crotch toward the back and stretched over her buttocks, the two corners then were wrapped around her waist and tied in the front. She looked marvelous, her long legs showed it off beautifully and when she appeared the audience hooted and hollered in appreciation. No wonder it was saved for last, it would have been a tough act to follow.

In 1945 Bain’s Music Store was the popular place in downtown Bremerton to buy 78 rpm phonograph records. Everyone appreciated the convenience offered by the three glass-enclosed listening booths. It was possible to listen to records before purchase.

A pale, bushy-haired young man, Matt, worked as a salesman. My friend Jackie took piano lessons from him. He invited her, my roommate and me to dinner at the small house he shared with two other young men. Jim was a struggling artist and Bob, the other house- mate, was a radio announcer for a Seattle radio station. He had his own program during which he softly read poetry while dreamy classical music played in the background. It was broadcast shortly before midnight We girls were very familiar with Bob’s rich voice and were faithful listeners to his romantic show. He always ended the program with the same verse. His voice would rise in a crescendo with the music as he read “And the night shall be filled with music, and the cares that infest the day will fold their tents like the Arabs, and silently steal away.” His voice faded to a gentle whisper with the last muted strains of the melody. The program was over. It was a lovely way to end the day. We always looked forward to his next program. Radio broadcasts allow dreams to fly free and imaginations to soar, creating faces to go with the voices. After listening to his program over many months I had a glorious vision of this passionate man and looked forward to meeting him at Matt’s dinner party.

It was a drizzling night when we three girls got off the bus on Callow Avenue and walked the block to their small rented house. Matt and the artist, greeted us and whisked away our wet raincoats. The room was lighted by many candles and a three-way floor lamp. We sat around the coffee table, drank a cocktail and turned our attention to Jim’s many paintings. It was obvious that this fellow painted pictures on anything he could reach with a brush. His pictures, painted on cardboard, cambric and loose canvas, were stretched and nailed flat to the living room walls. There was certainly no need to buy frames if one had a hammer and a handful of nails about. Bob, the radio announcer with the silky voice, was a nice fellow about thirty years old, very plain, a little plump and reserved. A malformed leg necessitated a corrective,thick-soled shoe and he walked with a slight limp. Afflictions don’t migrate through the airwaves and my image of the man with this marvelous radio voice crumbled. His appearance didn’t match his voice.

We talked for a half-hour and then Matt switched the lamp to the lowest possible light, and sat down at the piano and played a scherzo. Then he began to softly play a Chopin nocturne. We sat quietly as Bob stood and read poetry, silhouetted in the dimly- lighted hall near the piano. These guys were pulling out all the stops for us that night. Bob read beautifully. How fortunate that he had this great talent. The piano and poetry set us in a good mood to go to the kitchen for dinner.

Again we came upon more artistic creations by Jim. He had painted a four by six foot mural directly on one kitchen wall. When he had run out of money for canvas he yanked the old green cambric from the roller of every pull-down shade in the house and used it as a painting canvas. This explained the drafty kitchen with bare windows and the fluttery candle flames. Jim was a painter afflicted with a frantic form of creative frenzy. He was unstoppable. It was an interesting and enjoyable evening. We occasionally saw the pianist in the Music Store after that, but we never saw his interesting roommates again. We continued to listen to the announcer read poetry on the radio.

Many of our coffee breaks at the Studio were spent at the Olberg Drug Store. Mr. Olberg, a plump, balding man, had been in business on this corner for many years.

In addition to the usual drug store trappings, there was a beauty parlor near the pharmacy and a lunch and soda counter with eight or nine booths in a back room.

A half-block away from Olberg’s were the offices of the Puget Sound Power and Light Company where residents paid their electric bills and made inquiries. The manager of the company was a large, scholarly man who was fond of quoting Shakespeare. He reminded one of Orson Welles. He was a very popular speaker for luncheons and dinners around town and was frequently guest speaker at the local Little Theater annual ‘Oscar’ banquets. He relished the opportunity to embellish his speeches with scholarly quotations and prose.

The offices of their few electrical engineers were In the back half of the Puget Sound Power building. I am not sure what job Frankie Ames did for Puget Power, but this gregarious, short fellow seemed to be everywhere downtown at once, either on foot or in his Cadillac convertible. He was well known and rarely sat down for his coffee at the Drug Store. He was usually seen leaning between two seated customers, exchanging news and views. He was the quintessential stool hopper.

One day he did his leaning by my counter stool to tell of a newly hired engineer he wanted me to meet. I agreed to meet Frankie and this new engineer during coffee break the next day. Later in the day, I was with a customer in the Portrait Studio. I glanced at the front windows to see Frankie and a blonde man feigning interest in the window display and peering into the studio. I knew instantly that this good looking fellow was my date for coffee the next day. He fit Frankie’s description perfectly and I really looked forward to that coffee break.

This is how I met Lyle in July of 1948. A cup of coffee at a drug store soda fountain. Before long we were seeing each other almost every day. I was still active at nights in the Little Theater and the Arthur Murray Studio, but we found lots of time to be together.

Marion, our Studio colorist, was active in the Little Theater off Broadway, also known as the Bremerton Community Theater. Yes, it was off Broadway, but it was far from the Great White Way of New York City. Our Broadway was one-half block long and a half-block away from the Puget Sound Power and Light Company sub-station. The small 78- seat theater building was a small bungalow in a residential area, described by Bob Montgomery, one of the theater members, as being “A cross between a sharecropper’s cabin in Mississippi and an abandoned property.” When someone flushed the toilet, it was heard by the audience.

One night Marion and I went to the theater tryouts for the coming play, Dover Road. My only acting experience had been in High School plays so it was great to be selected for the role of Edith, the eccentric maid. It was a good part.

The Little Theater was a magnet for the eccentric. Self-acclaimed professional actors, breezed into town, and mingled at the Little Theater telling us of amazing, possibly exaggerated, New York Broadway credentials. We were excited to meet anyone who had experienced life on the REAL Broadway. This eagerness made us gullible and accepting of the exotic pasts many of these newcomers created for themselves. No one questioned why someone with such an impressive past would spend his time at this small, unknown west coast theater. Most of our directors were experienced drama coaches or former drama students. One director sold autos at his father’s local dealership, but his heart was in the theater.

A couple World War II veterans with noble battle records were trying to rebuild their lives. One frail fellow, a former Japanese prisoner, was a survivor of the Bataan death march in the Pacific war. A number of divorcées found an outlet of expression as well as romances with younger actors. A Naval Commander from the Shipyard, his wife and brother-in-law were surprising participants. This eclectic mix was enlivened by some very flamboyant men who also gravitated to the theater culture.

Once cast, a play rehearsed three nights a week for six weeks. When it opened we performed on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights for another six weeks. Service clubs purchased all seats for an evening performance and resold the marked- up tickets as a fund- raiser. This guaranteed the theater a full house and a specified income for every performance. This, in turn, paid royalties, expenses and hopefully financed the next selected play. The theater didn’t get rich, it got by.

The dressing rooms were cramped and had only one makeup table mirror. I know we all shared a single lipstick brush that had been used by every cast member for the last dozen years. One night, I was on stage, the butler was to deliver a thermometer on a tray so I could take Preston’s temperature. The butler came on stage carefully carrying the tray, I was appalled to see only one item on the tray and it was not the thermometer. It was the uncapped bright red Lucite lipstick brush about four inches long. Somebody back at the makeup table was probably looking for it at that very moment. With his back toward the audience. The butler helplessly mouthed the words, “It was all I could find.” The prop person had blundered so the butler hastily grabbed the lipstick brush. I quickly popped it into Preston’s mouth, brush end first. Yuk. The show must go on.

Practical jokes happened during many performances. These little surprises were concocted to see if an actor would fall out of character, break up or become flustered. They were probably old clinker pranks that had been used for years and transported by acting groups from theater to theater. When telegrams or letters were delivered to be read on stage, the actor sometimes found the opened telegram read, “Who in the Hell told you you could act?”, instead of the proper message.

During the run of one play, the stage set was a high Manhattan penthouse with windows overlooking city lights. One night, Bill Larson, who was not in the play, impulsively grabbed a towel backstage. Standing in the small passageway behind the back of the set, he pretended to wash the exterior of the penthouse windows during the performance, in view of the audience. During a different performance, an actor went to get a coat from a closet on stage and found Bill, looking unconscious, pretending to be hanging by his necktie from the closet ceiling, this time out of the audiences view. One would suddenly learn, during the performance, that real liquor was substituted for the tea in the teapot, and an occasional raw egg floated in the bottom of someone’s teacup. There would be a few quick coughs after these discoveries.

The final performance of every six-week run was celebrated with a cast party at someone’s home. One party was at a modest house along the waterfront rented by Len and his wife.

Len was in his early forties, his belly inflated by too many beers and his voice raspy from smoking the ever-present cigarette that dangled where its paper adhered to his lower lip. He never set his cigarette in an ash tray, it just hung there conveniently stuck to his lip until he flipped it up for another drag. The continual upward wisps of smoke put his eyes a permanent defensive squint.

We could hear the music playing when we arrived for the party, but the house was dark. Light was provided by lanterns and candles. This atmosphere was not planned. Len hadn’t paid his utility bill. Puget Sound Power and Light Company had turned off his lights, but the party went on as scheduled. Big Len and his huge string bass made a memorable silhouette against the lantern light. He was backed up by a piano and drums. His pudgy fingers viciously snapped those strings and the deep tone bounced off the walls in that small room. He greeted us with a nod of his head and the smoke from the dangling cigarette stuck to his lip made a jerky zig-zag design before it merged with the layer of cigarette smoke hanging in the room. Len was determined we should all have a good time.

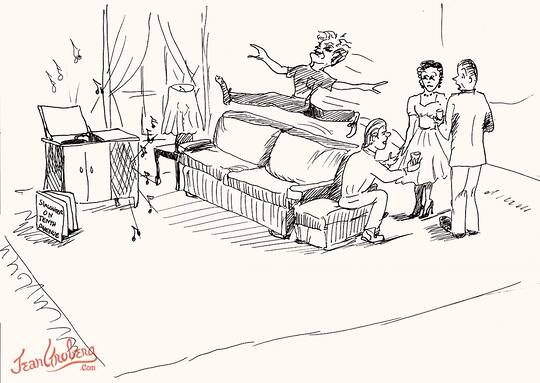

The cast was treated to another party at the Preston’s home on Officer’s Row in the Shipyard. Culture was running rampant that night. Some members gathered around the 78 rpm record cabinet to hear Judith Anderson performing Medea. Later the syncopated sounds of symphonic jazz music, Slaughter On Tenth Avenue blasted through the living room. It was loud, it was good and it was moving. Oh my, it was moving.

I had invited Lyle to this party and we were standing behind one of the couches in the center of the room keeping a wary eye on Rick, the newest East Coast arrival to our theater group. Rick spoke of extensive New York experience - and he could dance. How he danced! That Slaughter music boiled up inside him, erupting into an athletic solo performance that spun him all over the room. A cigarette pack bulged his tight tee shirt pocket and he wore slacks. He twirled, he leaped, he fell to his knees and slid on the carpeted floors only to rise for more leaps and pirouettes We quickly stepped aside to make room as he bounded toward us for a high hurdle over the couch, landing again on his knees for another fast spin. He was good. He was in his own little world, mindless of his surroundings and not one bit concerned about making a spectacle of himself. When the spirit moved Rick, he MOVED. One has to admire that flow of artistic expression, free from the anxiety of critique. When the music mercifully came to an end, he collapsed on the floor like a wet, limp fallen leaf. No one had taken notice of this passionate performance. Most were talking with broad hand gestures, completely absorbed in their own animated conversations.

Rob, another theater member was 24 years old. He had spent his early years in Germany and repatriated when Hitler became aggressive before World War II. Warships were one of his hobbies. He had large envelopes filled with cardboard cutouts of overhead views of all the ships in the United States Naval fleet and other major countries, all drawn to scale. Spreading these huge armadas over the carpeted floor, he ‘fought’ naval battles and planned strategic maneuvers. He returned home one time to discover his apartment had been entered during his absence and someone had searched through his personal possessions and many ship envelopes. He felt he was being watched by the FBI because of his early background in Germany, his interest in the fleet and the fact that he lived on the Naval Base at the home of his Naval Commander brother-in-law. A security- sensitive arrangement. He may have been correct. He also could have had an active imagination that enjoyed intrigue.

The Theater group could be dramatic and creative no matter what the event. When Lyle and I became engaged, I told my friends, “No bridal shower, please.” I just didn’t want one of these awkward events. One day a black-bordered invitation came in the mail inviting me to “A Wake to Mourn our Nearly Departed, Jean Mertz and Lyle Groberg”. It was to be held at home of two active theater members. On the afternoon of the Wake, Lyle and I entered into the spirit of the event and ordered delivery of a floral funeral spray mounted on a stand. The wide ribbon bore gold foil lettering that read “Rest in Peace”. When we arrived for the Wake, the mourning couples were wearing black arm bands. Heavy organ funeral music played loudly and a corpse, respectfully covered with a white sheet, reposed on a couch by the fireplace. The funeral theme was carried throughout the evening. Cemetery stones, with epitaphs were used as dinner place cards. After our dinner we learned we were attending a well disguised shower. Showers can be fun.

The above title are the words used by the Arthur Murray Dance Studio in their singing TV and radio commercials in the late 1940’s. Arthur Murray magazine advertisements of the 1930’s and 1940’s always pictured a series of small black footprints illustrating dance steps. Mr. Murray and his wife were famous dance partners who had established dance studios throughout the United States and Hawaii. In 1947 the Arthur Murray Dance Studio in Bremerton was dancing away on the second floor of the building next door to the Portrait Studio and Modeling School where I was employed. It was not unusual to encounter the Dance Director during a coffee break at Olberg’s Drug Store, a half-block down the street.

One time she offered me a job as an evening dance instructor. They would train me to teach dancing the Arthur Murray way and I would work 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. each night. I loved to dance and decided I could handle this along with my studio job that ended at 5:30 p.m.. I would eat, refresh myself and meet my first student at 6:00 p.m..

Arthur Murray had stringent employee rules that would not be tolerated in this day and age. The women were paid $1.20 per hour and the men were paid $1.30 an hour. “Men were the breadwinners,” was the explanation given to women when they inquired about the wage differential. Women accepted it. We were all single young people. The lone, twenty- one year old male instructor in our group was no more a breadwinner than the female teachers. A clause in our contract prohibited us from teaching dancing within 50 miles of Arthur Murray studios for three years after leaving Murray’s employment.

The men instructors wore suits. Women instructors were required to wear high heels, nylons and a dress. We sometimes wore full skirts over the swishy taffeta petticoats that were in vogue along with those open toed shoes. When a student stepped on my toes and ruined a pair of hosiery, it pretty much lost one hour’s salary. We were pleased when the comfortable ‘Baby Doll’ ankle-strap shoes became popular. The enclosed heel cup, plus a small strap around the ankle prevented the friction that caused painful heel blisters.

Teachers were forbidden to pass free time in the reception area. We waited for our students in an enclosed teacher’s gathering room behind the reception desk. There were three ballrooms, one for foxtrots and waltzes and the other for Latin dances.

There were was one male instructor and four female instructors. My very first student was a single forty-year-old man with a lumbering walk and erratic gait. He had one leg unusually longer that caused a jerky sort of dancing. It took several lessons before I realized why he lurched forward in an uneven manner and frequently crushed my foot. I doubt that I made a fantastic dancer out of him, but perhaps it helped him find a wife.

One student’s name was Mr. Nakashima. He was a very polite, young Asian man who came directly from his job at the Shipyard. He would quickly slide his round-topped, black metal lunch pail behind a chair in the reception room and sit down. The receptionist came back to the teachers room and announced, “Mr. Nakashima is here, Miss Mertz.” It had only been two or three years since our country had dropped atom bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima. The other teachers were quick to note that my student’s name contained syllables from each of these two unfortunate cities. They enjoyed deliberately turning the words around and they would say to me,“Mr. Hiroshima is here, or Mr. Nagasaki is here,” This foolishness in the teachers room caused me to make the embarrassing blunder one night of greeting my student with, “Good Evening, Mr. Nagasaki.” As soon as the words left my lips I felt terrible.

I was occasionally assigned a student in the over-sixty age bracket. Usually they were taking lessons to please a wife who enjoyed dancing. One sixty-year old student had been recently divorced and hoped that dancing might help his social life. He had worked outdoors for years as a lineman for the telephone or power company. I began by teaching him the foxtrot and waltz. He soon decided he wanted to dance with younger women and wanted to learn the jitterbug and swing. I was twenty-two, and just didn’t think about his age and physical conditioning. One night, after dancing a jitterbug to Glen Miller’s ‘In The Mood’, I noticed many shiny spots on the floor. Poor Mr. Engman was perspiring like a steel worker and the sweat was plopping on the floor in huge quarter-size drops. I switched to a slower song and blotted up the wet spots before someone slipped. When his lesson series was finished he gave me a gold compact with a ballerina on the lid. She had a red jewel for her face. He said that reminded him that my face always got red when he twirled me around. I don’t really believe that, but it made a nice little reason to give me the compact, which I still have.

Girls dressed up for dates in 1948. This meant high heels, nylon stockings, girdles, a skirt and blouse, or a dress and perhaps a hat. The fellows wore a sport jacket and slacks and a nice sport shirt. A dinner date was a really-dress-up event. Lyle would wear a suit and tie and I wore one of my best outfits. The only time you wore slacks on dates, was to go on a picnic, hiking or walking date.

Lyle’s Reserve Naval Officer status gained us access to the Officer’s Club in the Shipyard. We enjoyed their quiet, spacious dining room, the elaborate buffets, and dancing to live music on weekends. There were concerts, movies and plays in Seattle, and Bremerton.

We were frequent walkers and paths about Bremerton provided many views of the inlets and bays of Puget Sound, even occasional glimpses of the Olympic Mountains and majestic Mount Rainier. The waterways were always active with an assortment of ferries, Naval ships and occasional tugboats towing barges or rafts of logs harvested in local forests.

Our dates became more adventuresome when Lyle bought a 1937 Ford sedan for about $800 from a fellow worker. It had been lovingly outfitted with accessories by its first owner. This gray mound of metal with front wing window vents, had a spotlight, a knob and a fuzzy fabric cover with elasticized edges covering the steering wheel. A five-inch fan clamped to the steering post kept the windshield free of steam and frost. We took many drives and the car limped home from more than one destination, much to Lyle’s chagrin.

Bobby was a casual friend to all of us girls. He was a short, 23 year old entrepreneur with a new idea to earn extra money on Christmas. He placed an ad in the paper that read ‘Have Santa Claus visit your home on Christmas Eve - $3.00.’ And Bobby, never one to throw money away, made his own Santa Claus suit. Since we girls were planning to have an open house on Christmas Eve, we thought a brief visit by Santa Claus would give our party a little surprise. He agreed to do this.

Our party was in full swing, the Christmas tree lights were shining brightly, lighted candles on the coffee table and the side tables by the davenport decorated the room. Music was playing and the ten to twelve guests were walking about with their Tom and Jerry drinks in hand.

At 9:00 the doorbell rang and there stood Santa Claus. The guests laughed and screamed with delight as he entered, but Santa was in a hurry. He was running late because he was unable to locate the next house on his schedule. He made a beeline for the telephone to call that client for further directions. As he reached for the telephone, the sleeve of his home-made Santa suit brushed over a nearby candle igniting the white cotton batting stitched to the cuff. He dropped the telephone and pounded the sleeve against his belly. This ignited the cotton on the front of his suit. Obviously Santa had not made his costume out of fire-resistant cotton.

Lyle and Ken threw him onto the floor, wrapped him in one of Ma’s handy homemade rag rugs and put out the fire. Santa was not injured. He quickly stood up and hastily said, “Oh, I have another suit at home.” He was a blur of red, white and black as he sped out the front door, hurrying home to make a costume change.

We told our friends, “Santa was really burned up when he left our place last night.” In later life, Santa managed money so well that he ended up as President of a local bank.

My room mate and I frequently double-dated. One of her dates became Lyle’s best man at our wedding. Ben was a thoughtful young man who lived out on a wharf out on Puget Sound near Gleason Island. His family had been farming oysters for years and Ben slept pretty close to the Oyster Farm. One might say he slept right on top of it. He lived in the Oyster warehouse on the dock. His flexible rooms could be increased in area by simply moving a few cartons of canned oysters to the left or the right. It was simple, it was damp and it was no doubt cheap. Looking out the warehouse door, one could see the stakes marking the oyster beds out beyond the tide flats. He and his brother were putting all their resources into a fledgling log company making log houses using specially cut logs, somewhat like the Lincoln Log toys. They had already built a log church and a dwelling occupied by his brother.

In 1949 I accepted a job for more pay as Credit Manager at the Fuller Paint Company branch in Bremerton. The title seemed officious for what I did, which was the paper work for the branch. Any decisions about issuing credit to paint contractors had been made many years before I arrived on the scene. I did the mathematical computations for glass installation bids on new constructions working from blueprints. The bids involved mirrors, plate glass and Carrara glass, the glistening solid color glass square tiles so popular for facades of commercial buildings in the 1950’s.

Each morning when I arrived at work three or four painting contractors were already in the store selecting paint for that work day. Many of them mixed their own paints from the dry pigments purchased by the pound from big bins in the back room. The glass department in the basement employed three or four jovial glaziers. One time they had to replace a mirror in a bawdy house that occupied the rooms above one of the downtown stores. You could hear them shouting, laughing and making jokes as they loaded the mirror on the truck that morning and when they returned they were full of more stories and jokes.

Fuller Paint Store surroundings were not as elegant as the Studio. I was there a year when the whole office operation was moved back to the Seattle head office. I was due to get married in a month so I applied for a job back in the Shipyard in 1950.

A job in the Shipyard during peacetime was much different. I was now employed in the Beneficial Suggestions Department and it was fairly interesting work in a small office of seven people.

Shipyard employees submitted ‘Beneficial’ suggestions relating to money-saving, efficiency or safety. We processed their submissions, routing them to the pertinent departments for comment, acceptance or rejection. Once adopted, the suggestions were evaluated for the projected monetary savings to the government. Some of the suggestions were brilliant, some funny and some just plain stupid. A large percentage of the suggestions were hand written.

Don, a laborer in one the Machine Shops submitted over thirty suggestions. He held the record for the most ideas submitted. The one-line titles, for him alone, filled several 3 x 5 file cards. His strange mind bent toward the bizarre. Most of his weird ideas depicted ways to kill someone. He dwelt on complicated scenarios and Rube Goldberg type contraptions. Some were plans for simple tools. His handwriting appeared to be that of a third grader. Some pages had fairly good illustrations but all were disturbing. He suggested that human hair be ground up really fine, soaked in arsenic and put in the pepper shakers of the enemy. Another time he illustrated a knife that had the curve of the blade ‘exactly like that of a man’s back’. The sheer volume of sick submissions was appalling. We were bound by office rules to treat each idea with respect and forward it to the proper offices for evaluation. We were beginning to think that Mr. Don should also be sent somewhere for evaluation, along with his ideas.

Finally, our supervisor decided he had better have old Don in to the office for a talk. He warned the rest of us in the office that Don was coming. We were very curious about his appearance. Don turned out to be about 30 years old. He was a large-boned, slow- moving man with long arms and legs who lumbered into the office wearing denim overalls. Our supervisor was acutely uncomfortable welcoming this peculiar fellow into the office, and searched for a cordial opening sentence. It seemed a simple, “Hello,” or, “How do you do?” would not suffice, so he blurted an odd greeting: “Well, you sure come up with lots of ways to kill people.” The office fell silent. The rest of us squirmed at our desks, felt uncomfortable and turned our heads in embarrassment, pretending we didn’t hear this ill- chosen greeting. The keys of our typewriters flew with contrived activity. This private meeting seemed to energize old Mr. Don’s warped mind even more and we were treated to a fresh flurry of new killer ideas during the following few weeks.

Another employee submitted a suggestion that urinals be placed in the womens restrooms. Again the suggestion followed the usual routing through Managers of all the Shipyard departments. The fact that all these Managers were men did not stop them from offering their opinions on the intricacies of womens bathroom habits and evaluating the merit of this particular suggestion. Each added his opinion to the long list that accumulated as the document went through the usual channels. They felt no need to consult with any women. It was not adopted.

Wooden gates were replaced by iron and additional walk- through gates added during World War II.