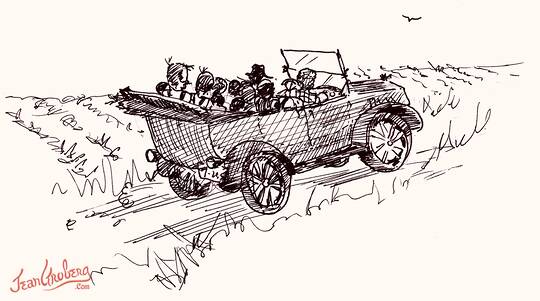

Come Away With Me in the Model-T

The Model T Ford wheezed, coughed and sputtered down the South Dakota dirt road. Pa was driving his wife and their many children to view the crops. The canvas top was down and we all were set to enjoy this summer evening ride in the early 1930’s.

Those were the prosperous years in the late 1920’s. We had rain. We had a crop. We had a Model-T car. We had a modest cash flow. We had ten kids, all born between 1911 and 1929: Donald, Howard, Dorothy, Floyd, Helen, Thelma, Verna, Jean, Joyce and Bruce.

It was a real treat when Pa suggested a ride after the supper dishes were done. He would then step clear of the stampede as ten kids ran to claim their seats in the Model-T. Two or three little ones sat up front with Ma and Pa and the other small ones stood in back or sat in someone’s lap. One of the older boys turned the crank; the motor coughed a couple times before it took hold. He would then leap into the back seat and we took off down the road to examine any field growing within a five mile radius. There was nothing like traveling in an topless Model T so fast the mosquitoes couldn’t keep up.

We admired the height of the crops, how farmer Mitchell had planted corn in nice straight rows, or what a fine job another had done ‘checking’ corn -- planting it in a pattern resulting in diagonal rows visible from many angles.

On one evening drive, 5-year old Thelma bounced out of the back seat and fell on her behind on the dirt road. It was a while before the bigger kids convinced Pa there was a girl overboard. Thelma, by then, was up and chasing the Model T shouting, “Wait for me, wait for me!

One evening Pa decided to drive us all into Houghton to see Ma’s parents, Grandma and Grandpa Bartholome. We climbed into the Model-T. Once it was cranked and running, we drove out of the yard. Two miles down the road we drove up behind the car of Uncle John and Aunt Ella and their ten children. They were also driving to Grandma’s house, and with a three block head start. That pretty much eliminated Grandma’s as a destination. Pa said, “That will be too many kids.” He was correct. Twenty kids at one time would have been a bit too much. We returned home.

Another evening Pa and Ma decided to drive directly to Uncle John and Aunt Ella’s farm. Let their ten kids mix it up with our ten kids, their six girls with our six girls and their four boys could play with our four boys. A matched set of kids. Aunt Ella made a big dishpan of popcorn and all twenty cousins ate it while sitting in a huge circle. The older boys showed off shamelessly, throwing popcorn in the air and catching it in their mouth.

Alas, the rains stopped and the crops died. The money stopped and prosperity took a long holiday. The automotive marvels, the Model-T’s and the Model-A’s, symbols of those better days, became rusting old car bodies abandoned behind the plum trees where we played and where turkey hens hid their nests. The old Whippet sedan, still sporting rotting wisps of velour upholstery, was the last car to join the broken, retired auto bodies in the trees.

As our family grew older, drought was persistent and the economy floundered. Challenging times were here.

During the next few years the drought and depression controlled our lives. It was everywhere. We not only lived the drought, we breathed it. Yes, we breathed the sand blown by continual dry winds.

The fields were reduced to shifting sands. We had no crops and no money. During the early 1930’s, Pa was gone for more than a week looking for work, hoping to find areas where farming conditions were better. He returned jobless to Ma and his house full of kids. I stood in the corner of the living room as he sat on a chair behind the stove, put his head in his hands and wept. Ma sat on his lap and comforted him and we all kept our distance during this private time.

The depression and drought wore us down and the government became involved. Starving cattle were herded from the surrounding communities to the nearest town where they were driven into freshly-dug deep pit. Farmers stood around the edge of the pit and shot the poor beasts in their grave. The garden wouldn’t grow without rain and it was under constant assault by wind-driven sand. The government provided a food commodities relief program. There was probably a stigma and damaged pride our endured by our parents to pick up the ‘relief’ food in town. We were not alone, many farmers were in the same predicament. We received food with plain generic labels that read ‘Not To Be Sold’. Cornmeal, raisins, rice, flour and dried milk were among the foodstuffs. That winter we had many simple suppers of Johnny Cake (cornbread) served in a bowl with Karo syrup and milk. We were introduced to our first grapefruit juice in cans marked ‘Not To Be Sold’.

The government employed people to sew very bad looking clothing using decent fabrics. When relief clothes were void of any beauty and literally shouted “RELIEF CLOTHES”! They challenged Ma’s creativity. She added recycled decorative pieces and nicer buttons. The government-made blue denim bib overalls with buttons replacing the suspender clasps and rivets were awful.

The Government created jobs by hiring local people to re- pad and recover old bed mattresses in a nearby town. It was useful endeavor that again put needed money into pockets of the farm families who did the work. Some of our sagging and stained mattresses were taken four miles away and came back with fresh, blue and white striped ticking. Howard, about 19, took part in the Civilian Conservation Corps program, building small dams and other conservation work. Most of his paycheck was sent home to support us.

Russian thistles, called ‘tumbleweed’, survived drought and wind. They emerged as tender fronds that grew into voluminous round bushes. Their tight network of thorny stems formed a ball two to three feet in diameter. When the bushes dried in the fall, their shallow roots slipped their moorings and the wind bounced them across the prairie spreading seeds and assuring a new thistle crop the following year. They were now tumbleweeds. Spontaneous, circular currents of whirlwinds spun a mixture of feathers, dust and tumbleweeds forty or fifty feet into the air on a wild twirling ride and just as suddenly run out of energy and drop the tumbleweeds to the ground. They were blown along roads and across fields until snared by woven wire fences. Dozens of them would become trapped in fenced corners of fields. We kids treated these round weeds as natures gift brought by the wind and used them as building material, piling them into wall and room configurations. Their thorns and branches readily hooked onto each other and they could be piled several feet high, wind permitting. Like the story of one of the Three Little Pigs who built his house of straw, our tumbleweed house stayed in place until the first big blow. It was a nuisance weed and we helped Pa pitchfork them into large piles for burning in the spring.